Designing Black Economic Mobility

.Oceana Andries is a Gallery Assistant at Poster House who also works as an independent arts writer.

The history of Black economic growth during the 20th and 21st centuries in the United States has been defined by significant turbulence, the result of systemic racism and discrimination. While Black working people developed a range of skills, such policies and practices often restricted their opportunities, inevitably limiting their economic mobility for decades. Through political and social-justice advocacy and protest, however, Black Americans gradually began to equalize their economic status with that of their white counterparts. Posters have played a key role in communicating these developments to the American public. A selection of works from the Poster House Collection (as well as one from the Library of Congress) focus on the Black Americans as they navigated the radical changes of this era.

United We Win (1942) by Alexander Liberman

Poster House Permanent Collection

Alexander Liberman’s United We Win (1942), commissioned by the War Manpower Commission (WMC) as part of an anti-discrimination campaign, presents an image of racial unity, depicting a Black man and a white man working together on an aircraft assembly line during World War II. The American flag hangs above the two men to highlight their shared identity while the quote below speaks to a common goal, “United We Win.” The poster emphasizes that such unity among working-class people of every background is necessary for victory.

Liberman was a prominent Ukrainian photographer, painter, and sculptor. When he was commissioned to design this poster by the WMC, he was actually the art editor at Vogue magazine. The WMC was a government agency responsible for managing the nation’s labor force during the war, and especially for recruiting workers for both war and civilian industries.

During the war, the draft created national labor shortages as working men went off to fight. The industrial sector now urgently needed workers, and this meant hiring them regardless of race or gender. According to General Frank McSherry, director of operations for the WMC, “employers can no longer afford to discriminate against Negroes and workers of other minority groups…Aliens, where it is possible under government restrictions, must be considered for war production jobs…We cannot afford to permit any preconceived prejudices or artificial hiring standards to interfere with the production of tanks, planes, and guns.”

Many of the Black Americans who served in the war enlisted in the hope that this would bring an end to racial restrictions and segregation. The poster below was issued by the U.S. Government Printing Office in 1942 in an effort to recruit Black Americans to all branches of the military. It shows heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis handling a bayoneted rifle. Louis had joined the army that year and was initially assigned to a segregated cavalry unit; he faced some criticism from Black Americans for enlisting in “a white man’s army.” His response was: “Lots of things wrong with America, but Hitler ain’t going to fix them.”

During his time in the army, Louis used his connections to assist Black soldiers. Notably, he asked his friend and lawyer, Truman Gibson, to help baseball legend Jackie Robinson, whose application to the Officer Candidate School had been inexplicably delayed for months. The army noticed Louis’s natural charisma and talent for raising soldiers’ morale and quickly assigned him to the Special Services Division, away from combat.

Pvt Joe Louis Says (1942) by an Unknown Designer

Image: Library of Congress

While there, he became the face of a recruitment campaign encouraging Black men to enlist. During his military career, Louis traveled 22,000 miles and staged 90 boxing matches for some 2 million soldiers. And while he often faced racism and segregation during this period, he also became a symbol of national unity and patriotism.

In June 1941, as the government prepared for war, and in response to the demands of Black leaders, Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 8802: Prohibition of Discrimination in the Defense Industry. It stated: “There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries and in Government, because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” But support for this development among Black American citizens was embodied by the slogan “Double Victory,” often shortened to “Double V,” a concept championed by the Pittsburgh Courier, then the most prominent Black newspaper in the United States. On January 31, 1942, it published a letter from James G. Thompson, a young Black American defense worker in Wichita, Kansas, titled “Should I Sacrifice to Live “Half-American”?” Thompson argues that “If this V sign means that to those now engaged in this great conflict, then let us colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within. For surely those who perpetrate these ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.”

Such efforts expanded the opportunities available to Black Americans in a range of war-related industries, including shipyards, factories, railroads, and administrative offices. However, this kind of integration was relatively short-lived and created a false sense of unity, as the emergence of the civil rights movement after the war would make abundantly clear.

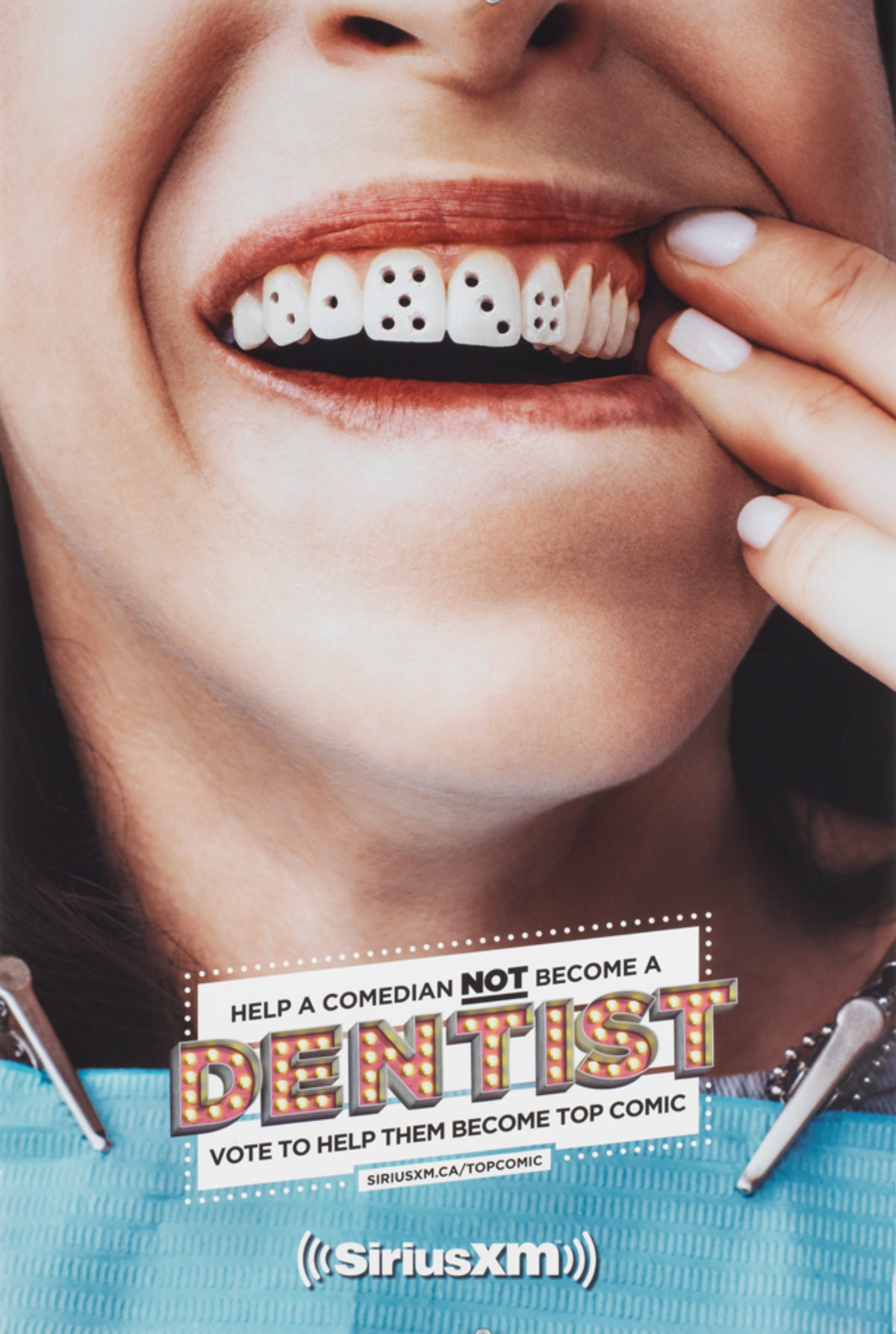

I Got My Job Through The New York Times (c. 1973) by Louis Silverstein

Poster House Permanent Collection

Some 30 years after these World War II poster campaigns, a Black woman is positioned as the face of the contemporary workplace in Louis Silverstein’s I Got My Job Through the New York Times. Her job title is given at the bottom of the poster as “Lab Technologist.” Until the mid-1960s, such roles had been largely inaccessible to Black Americans, especially Black women. After the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, and President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which prohibited discrimination against individuals based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in all conditions of employment, the economic landscape for Black Americans began widening.

Louis Silverstein was a white American artist and graphic designer. He joined the promotion department of the New York Times in 1952, eventually becoming the paper’s art director. The phrase “I got my job through The New York Times” was coined by Irvin S. Taubkin, the promotions manager, in 1954. Silverstein designed a campaign based on the phrase with the help of several photographers, and the posters soon began to appear throughout New York City. The advertisements, which became especially familiar to subway straphangers, boasted that a range of jobs could be found within its pages. They feature many Black Americans with titles ranging from consultant to hospital recreation worker and lab technologist. The campaign ran through the 1970s and was revived in 1999.

This advertisement unwittingly represents decades of obstacles among Black Americans for social and economic equality. The woman in the campaign did get her job through the New York Times but also through years of civil rights protests, executive orders, and feminist movements.

Give It Up For the Golden Age of Hip Hop (2005) by Kehinde Wiley

Poster House Permanent Collection

Kehinde Wiley’s Give It Up For the Golden Age of Hip Hop (2005) features the rapper Notorious B.I.G., also known as “Biggie.” To the right of the portrait is the information for VH1’s (Video Hits One) Hip Hop Honors ceremony, where awards are given on the basis of its honorees’ historical significance to hip-hop rather than the commercial value of their work.

Wiley is a prominent Black artist whose work is in the collections of such notable institutions as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum. (In 2017, he was commissioned to paint a portrait of former President Barack Obama for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.) The environment Wiley creates emphasises the larger economy of the hip-hop industry. He depicts Biggie as a gangster from the mob era of the mid-20th century, flaunting his economic power through style. The motif that adorns the background and Biggie himself is the fleur-de-lis, the stylized lily associated with the French crown. Through symbolism and styling, Wiley signals that the hip-hop honorees should be ranked culturally and perhaps economically with European royalty. VH1 also commissioned Wiley to paint portraits of other musicians honored at the 2005 event, among them Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Salt N- Pepa & Spinderella, and LL Cool J, as seen here.

Give it Up for the Golden Age of Hip Hop (2005) by Kehinde Wiley

Poster House Permanent Collection

Wiley’s Give It Up for the Golden Age of Hip Hop poster series commemorates a Black American musical legacy and marks a significant shift in the representation of Black figures. While there have clearly been many significant economic developments in the lives of Black Americans in recent decades, the title alone of a 2024 essay by Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, president of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, and Algernon Austin, former director of the Economic Policy Institute’s Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy, “The Best Black Economy in Generations—And Why It Isn’t Enough” speaks volumes. They note that: “With all of the advances made since 1960, the nation is still moving at a glacial pace when it comes to bridging Black/white inequality. If the country continues at the current rate, it would take over 500 years to bridge Black/white income inequality, and nearly 800 years to bridge Black/white wealth inequality.”

While great strides have clearly been made over decades, the continuing progress and solidity of Black economic growth remains a matter of serious concern. Each poster here, sometimes unwittingly, provides a glimpse of the ways in which government entities and individual communities have used posters to promote their specific economic agendas. Today, this visual history of some of the changes in Black economic development within the United States remains as pertinent and as resonant as ever.