Hidden. Found. Remembered.

.Dr. Cheryl D. Miller is a scholar and academic dedicated to ending the marginalization of BIPOC designers within the graphic design industry through her activism, writing, research, and archival vision.

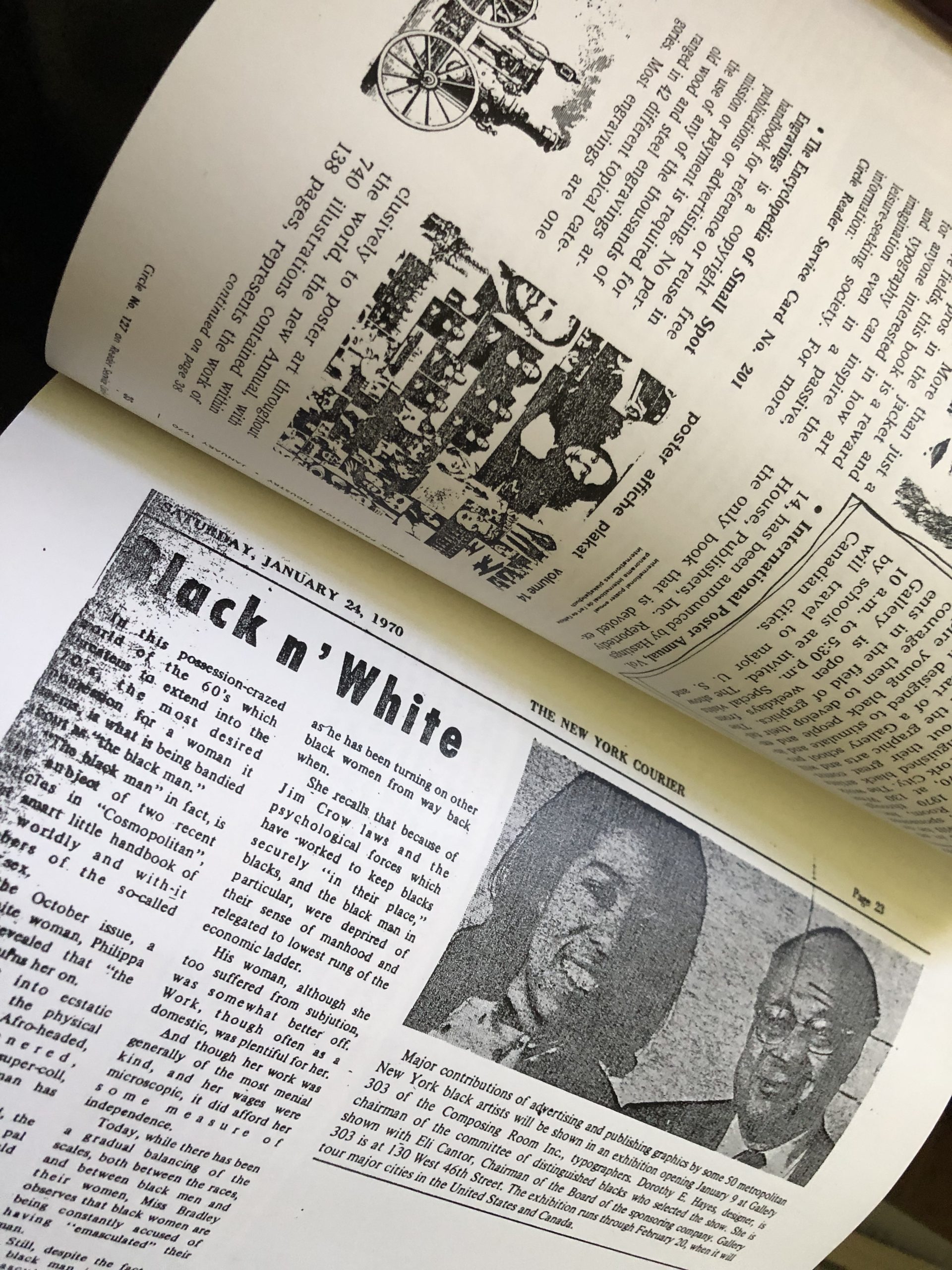

Martin Luther King’s assassination was a watershed moment for the closing of the civil rights movement. His murder moved the needle of change, especially in the fields of art and advertising. At the time, the New York City design community and related industry publishers began asking themselves, “Where are the Black designers?” As a young teen pursuing my education in the field, this is where I started my journey in advocacy for the recognition and inclusion of BIPOC artists throughout the trade.

Today, I am an educator seeking to integrate the white, Euro-Anglo Modernist historical design canon with more global histories, especially the story of Black graphic designers. In doing so, I have become a decolonizing historian and a revisionist academic looking to paint the complete picture of countless missing accounts. With an understanding of the importance of primary source material, my new mission is to collect ephemera from deceased Black designers. History books can’t be written without proper research, and proper research cannot be accomplished without discovering missing facts.

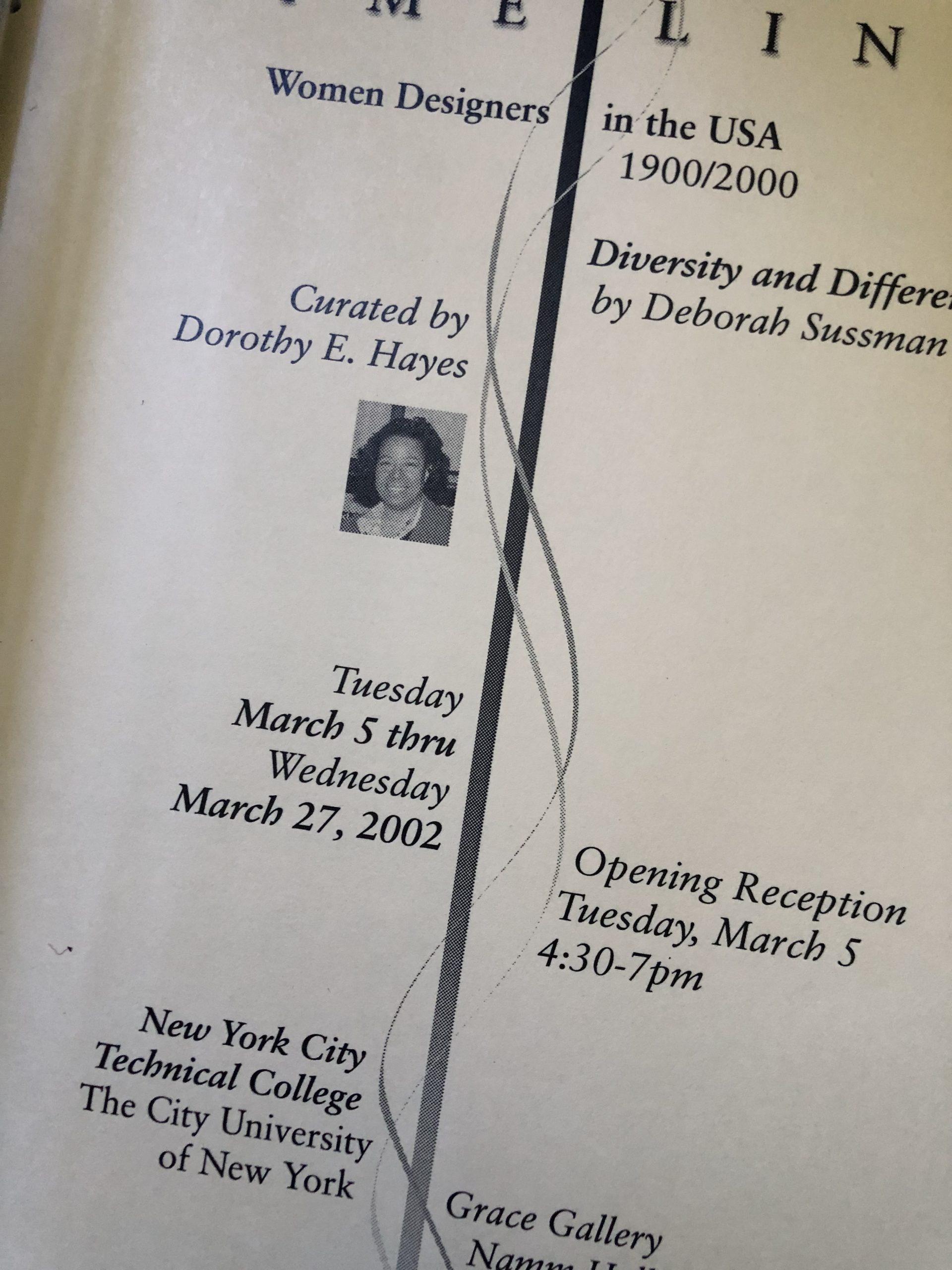

GBC Binder Pages of Dorothy’s detail narrative of the development of the exhibition. Dorothy Hayes papers (M2740). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford Libraries, Stanford, CA. Regina Roberts

Having lived through the civil rights era, I heard of Dorothy E. Hayes and sought to find and digitize her story. In the process, I discovered her estate had a well-organized collection of professional papers, including record keeping and memoir notes related to the 1970 exhibition “Black Graphic Artist in Graphic Communication.” Her niece spent the last ten years of Dorothy’s life with her and inherited her records and professional papers. In this, I discovered a treasure trove of exhibition memorabilia and content in her possession.

Dorothy had painstakingly kept the story of the exhibition in exact chronological order. She recorded details of the entire show from its inception through its touring across academic geographies. It was no question that Dorothy wanted her box of career documentation to be discovered. The family consented to donate Dorothy’s professional papers to the Stanford University Libraries’ collection, known now as the Black Graphic Design History Initiative.

GBC Binder Pages of Dorothy’s detail narrative of the development of the exhibition.

Dorothy Hayes papers (M2740). Dept. of Special Collections and

University Archives, Stanford Libraries, Stanford, CA.

Regina Roberts

Specifically, in Dorothy’s box of ephemera was a binder documenting the exhibit’s development. Her exhibition was created to show the design community that Black artists and creatives were and are active practitioners in the industry. She writes of the January 1970 show, “one purpose of the exhibition is to show the advertising and publishing industries…the vast reservoir of talent, which is being unused, misused or underused.” It is the most valuable document in the collection and is an incredible memoir narrative about the exhibit. She continues, “A wide-ranging exhibition of graphic communication—including design, illustration, advertising, television commercials, and film—is currently on a two-year tour of art schools and colleges. Originated, planned, selected, and produced by Black artists, it presents the work of 49 Black men and women from the New York metropolitan area. Except for collections of fine arts assembled under museum auspices, it is believed to be the first exhibition in this country to present a representative showing of graphics by Black professional artists.”

GBC Binder Pages of Dorothy’s detail narrative of the development of the exhibition.

Dorothy Hayes papers (M2740). Dept. of Special Collections and

University Archives, Stanford Libraries, Stanford, CA.

Regina Roberts

Although groundbreaking for its time, most designers have yet to learn about the 1970 exhibition. I have done my best to memorialize the moving of the needle for design’s diversity, equity, and inclusion advocacy and to expand the knowledge of Dorothy E. Hayes and her 49 Black design colleague exhibitors.

Dorothy, we see you! Dorothy, we thank you!