I Must Protest! Peter Kennard & Visual Dissent

.“When political art is good it starts to be really interwoven with reality. The thing about that now in a time of grim politics, it just ends up being devastating”—Nadya Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot, the Financial Times, June 11, 2025

Some aspects of curating Fallout: Atoms for War and Peace brought back memories of my youth in the UK, none more so than the photomontage posters of Peter Kennard. In these antinuclear posters, he very cleverly combines found objects with both images and words appropriated from official government campaigns and establishment sources, turning them against their originators. They blend bold motifs with sly humor intended both to undercut the official messaging and reveal the duplicity within it.

There are 18 of Peter’s posters in the exhibition, which led one of my colleagues on a staff tour to ask me: “So what’s he like?” My immediate response, which I think still stands, was “Imagine Bernie Sanders as a quieter, less loquacious, British artist and you will have a fair idea of ideology and delivery.” I first met Peter as he walked me around his exhibition, Peter Kennard: Archive of Dissent, at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, which ran from July 2024 to January this year. Since then, I have visited him at his studio, a fascinating experience.

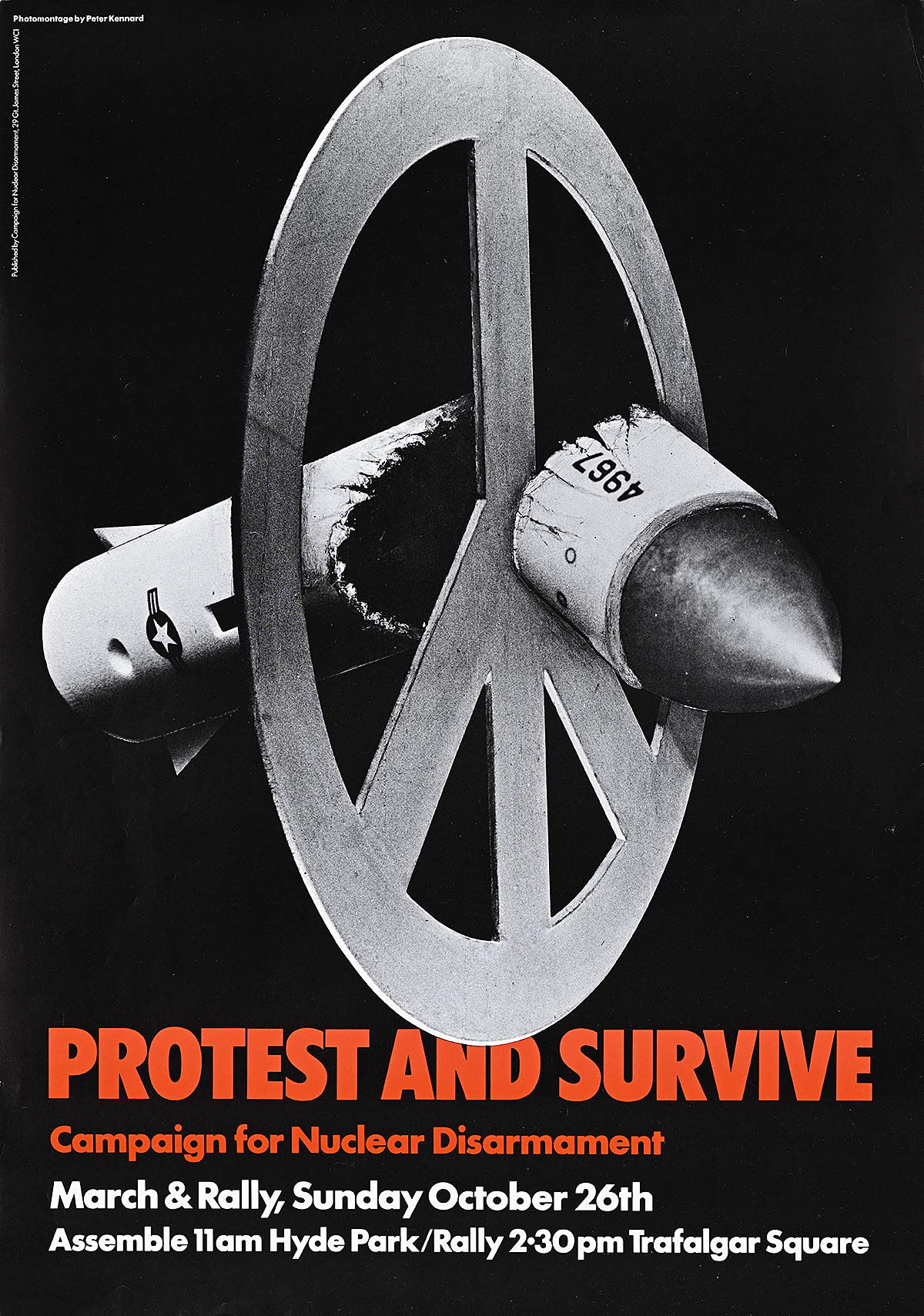

No Nuclear Weapons (1980), by Peter Kennard

Poster House Permanent Collection

Peter has been producing protest art or what might be deemed political art since the late 1960s. As he describes it, his work erupts from translating anger at oppression into image. Many of the images he made half a century ago reflect themes that are still current today. He originally studied as a painter, influenced by such artists as Francis Bacon, but he was drawn to activism by his opposition to the Vietnam War and soon found himself working in photomontage, where art and politics naturally came together. He was inspired in this by the German artist John Heartfield, best known for his anti-Nazi photomontages from the 1930s.

Loyalty for Loyalty/Greetings from the Führer (1934), by John Heartfield

Image Source: MoMA

Peter himself vividly explains his chosen medium and its impact: “it doesn’t present a ‘window on the world’ so much as a smashed mirror in which viewers see themselves reflected in the fragments of reality.” I find this concept particularly interesting, as we now live in a world where social media drives people ever further into tribes or factions. Peter’s posters seem to transcend that; he acknowledges his viewpoint and activism upfront but even if you do not agree with him, the smashed mirror forces you confront facets that maybe you would rather ignore. This is the subtlety of his pieces, the element that I referred to as the “sly humor.”

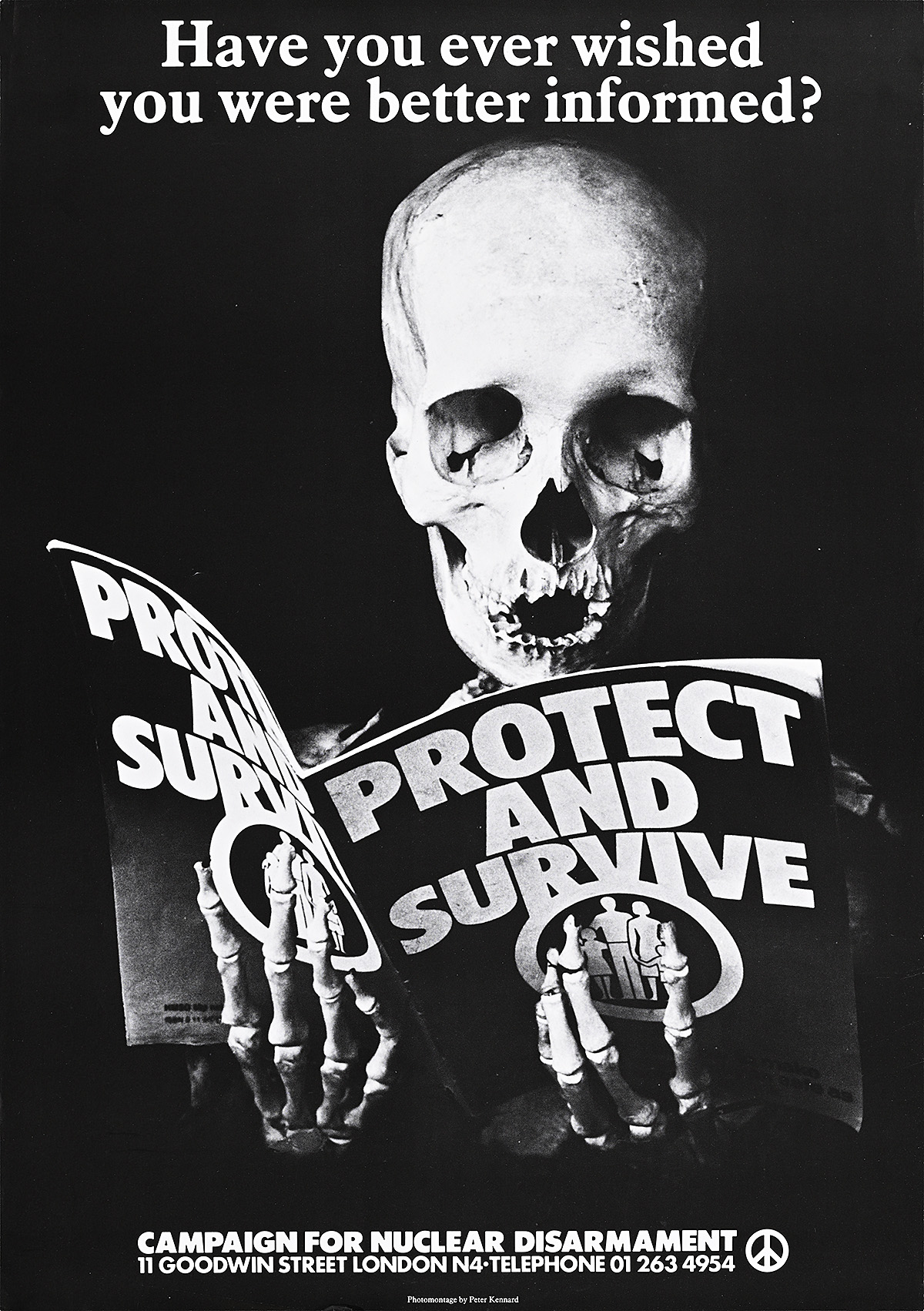

Protect and Survive (1980), by Peter Kennard

Poster House Permanent Collection

In the poster above, Kennard appropriates the advertising slogan for the London Times, the British “paper of record,” and rightly ridicules the government’s Protect and Survive PSA campaign. Peter began working during the analog age, and his art remains rooted in it. For this poster, he had his students at the Royal College of Art hold up the skeleton’s arms so that it appeared to be reading the pamphlet.

Fougasse, the great British designer of World War II propaganda posters, wrote about the relative value of shock and humor in propaganda produced in democratic countries—and came down firmly in favor of humor. As he wrote in his book A School of Purposes in 1946 “Horror’s lesson is a single distasteful shock—it may admittedly have a startling primary effect on the reader, and this primary effect may be twice or even ten times as great as that of humor—all the same the latter has, I am sure, a thousand times as many chances of getting past A, and through to B and C—that is of persuading the reader, and of keeping him persuaded.”

Peter’s posters on nuclear disarmament successfully shock with the sheer horror of their images at first glance, and on the second, make one laugh with grim humor at the sheer stupidity of a government that would advise you to have a fire extinguisher “handy” to deal with the fire risk presented by a nuclear fireball burning at 100 million degrees celsius (see the poster below). Another poster in the series, bearing the slogan Remove Net Curtains, 1985, lampoons the government directive to take down flammable curtains…In these posters, Peter is not mocking the genuinely terrifying concept of global nuclear destruction but rather the governmental cant suggesting that such an event might be survivable and that, obviously, the good guys will win in the end.

Target London/If you have a home fire extinguisher (1985), by Peter Kennard

Poster House Permanent Collection

When I was curating We Tried to Warn You: Fifty Years of Environmental Protest Posters, an exhibition shown at Poster House last year, my colleagues and I were forced to consider the question of whether or not the poster designers had succeeded as activists. Peter’s own view about this is both pragmatic, simple, and true to his belief system. As he wrote/narrated in his book Peter Kennard: Visual Dissent (2024), “Corporate control of our societies is more potent than when I first started out, but then so too is the resistance. Artists are ripping aside the corporate veil to fight against what we really have in common: the fight against profit at all costs and our struggles against racism, war, sexism, inequality and the climate disaster.”

The Guardian article below asks a similar version of the question in 1990, debating what the individual artist, in this case Peter, can do in the face of horror.

The Guardian (June 15, 1990)

While thinking about this I heard an interview with Billy Bragg, the British singer/songwriter and activist who shares similar beliefs to Peter. Bragg said on BBC Radio 4 “ Music has no agency, art has no agency, but, having said that, it does have power.” Peter’s posters have power.

That power is reflected in the timeless nature of his images that allows them to be revisited (sadly) as needed.

In 1980, he created, in typically idiosyncratic fashion, a poster for the British Campaign For Nuclear Disarmament (CND) showing a nuclear missile broken in two by the CND logo (the “peace sign” designed in 1958 by Gerald Holton). To do this he went to Hamleys, a celebrated London toy store. There he purchased a toy nuclear missile (I acknowledge it would be an unusual gift for a child), broke it with a hammer, spray-painted a cardboard CND sign, and put the two together. A new version of the poster can be seen below “in the wild” in a London Tube station in 2016, when there was a parliamentary vote about whether or not to renew the Trident nuclear weapons system. The issue remains, but the image, the visual counter argument is still powerful and relevant.

London Tube Station (2016)

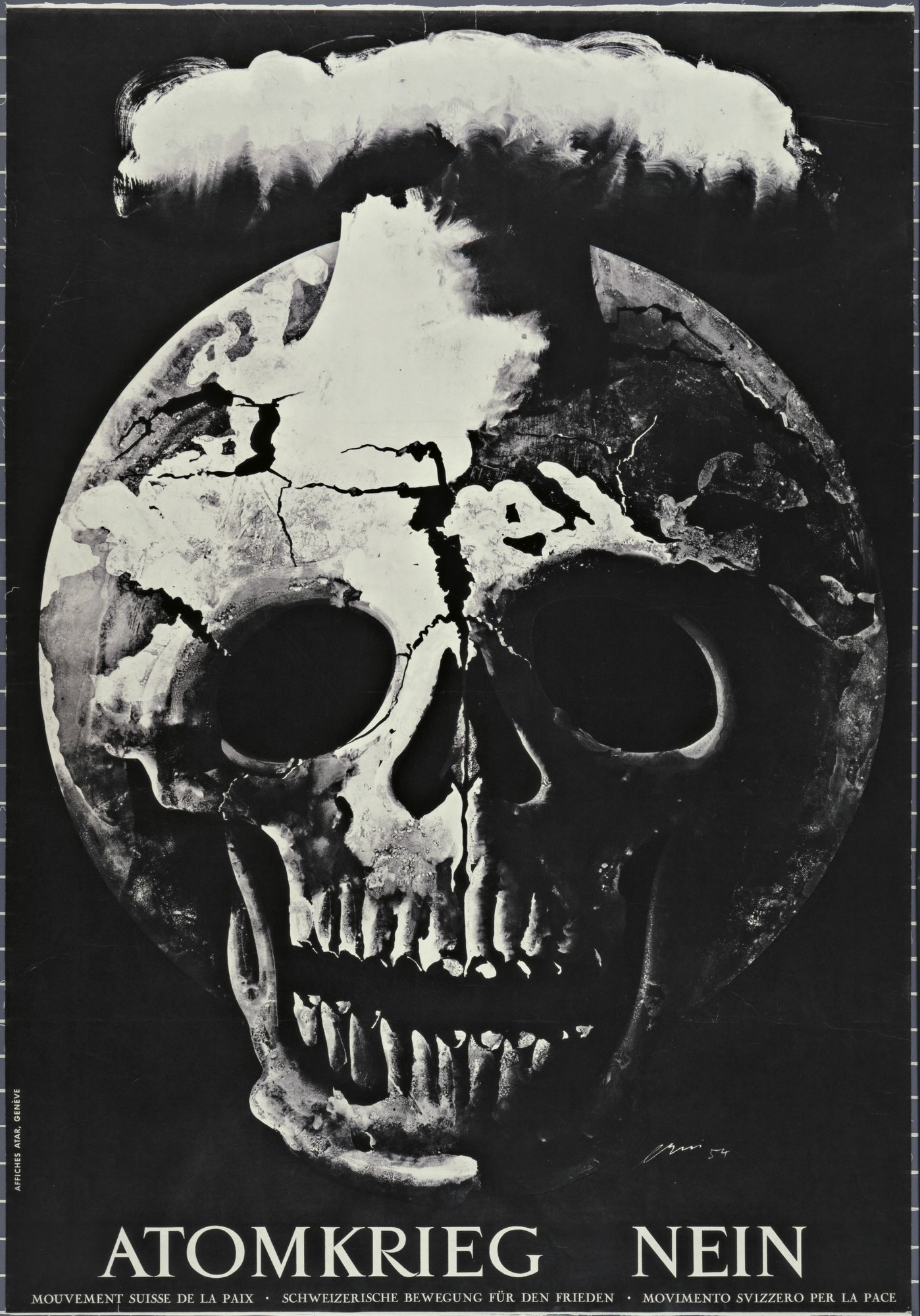

I started with a quote, and I shall finish with one—from Harold Pinter, the distinguished Nobel Prize-winning playwright, and one that seems particularly apt given some of Peter’s skeletal imagery. In the foreword to Domesday Book (1999), he wrote that “Kennard sees the skull beneath the skin all right: an era dominated by greed, indifference, ruthlessness, naked force against the powerless; the Holy Grail of the big buck.”