The Crumbling Walls of Attica

.This digital handout was created in conjunction with the exhibition No Escape: The Legacy of Attica Lives! It is meant to showcase the influence of the Attica Uprising on issues of prison reform.

The Attica Uprising was a landmark event in the history of the civil rights movement and of the United States. It exposed widespread mistreatment of inmates and significantly informed subsequent efforts for criminal-justice reform. In 1973, the prison population numbered an estimated two hundred thousand people, and, the United States consistently has the highest prison population per capita, with rates more than double those of other developed countries, according to the International Center for Prison Studies.

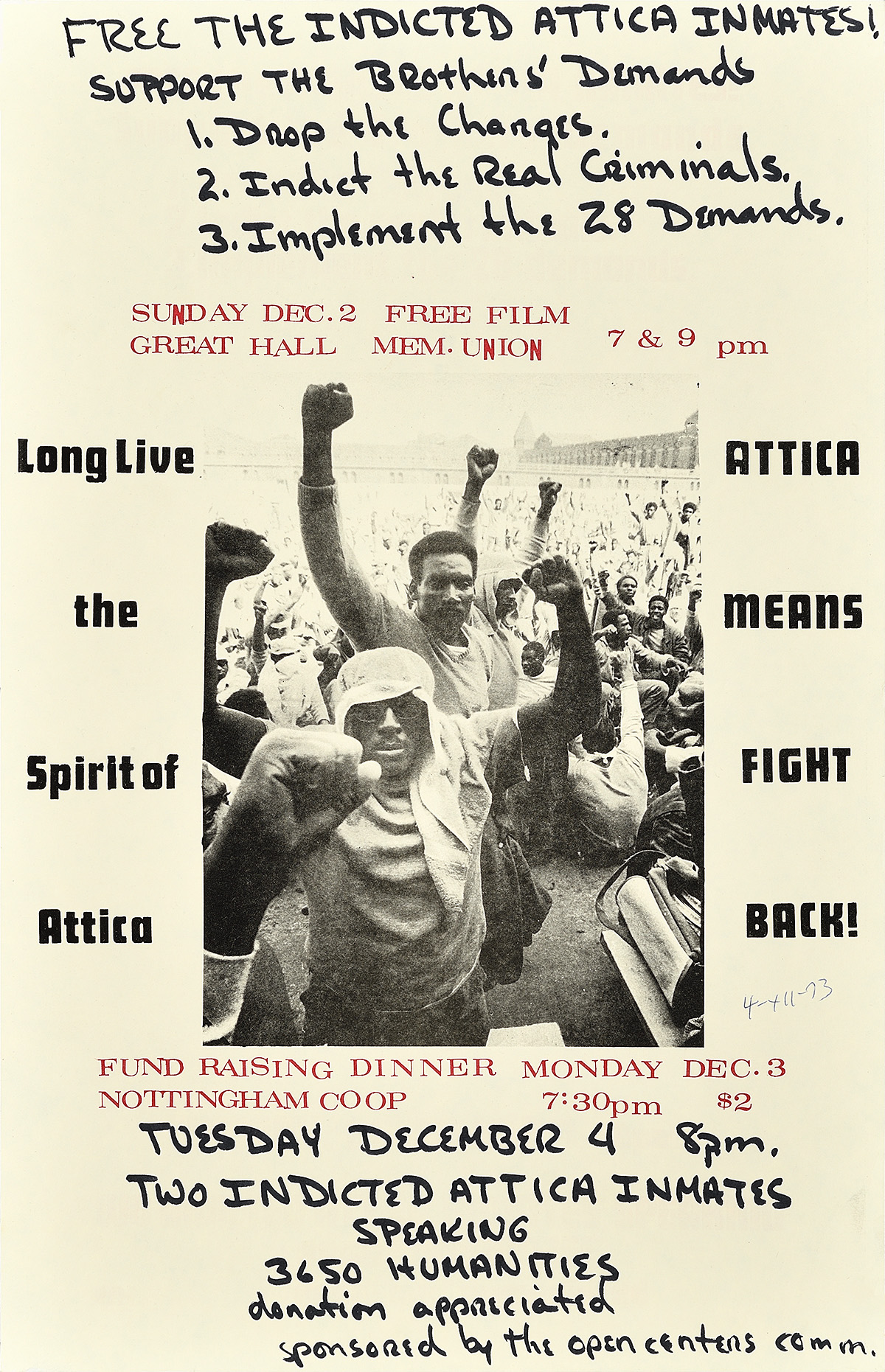

The Attica Uprising is indelibly marked on the memories of those incarcerated at the time, the organizers, and the families of those killed. After enduring dehumanizing conditions for years, a group of visionary men organized a protest at the prison; it began on September 9, 1971, when they rioted and took hostage 42 members of the prison staff. The siege continued for four intense days. On that first day, their Declaration to the People of America listed five demands as preconditions for ending their takeover of the prison. It was read out by Elliott Barkley. The catalyst for the uprising is thought to have been the killing of George Jackson, a political prisoner at San Quentin, under controversial circumstances. Officials claimed Jackson was attempting an escape when they shot him on August 21, 1971.

The inmates reported that the conditions inside Attica were inhumane. As in most correctional facilities and many American neighborhoods at the time, Black inmates were segregated from white inmates. Further, while Attica’s racially diverse prisoner population comprised 54 percent Black, 9 percent Latino, and 37 percent white inmates, the corrections officers were primarily white. The Attica Uprising thus also reflected the national racial tensions of the era and the disproportionate number of Black and Brown men incarcerated there represented wider societal inequalities. In addition, inmates were subjected to terrible food, poor hygiene conditions, and brutal treatment.

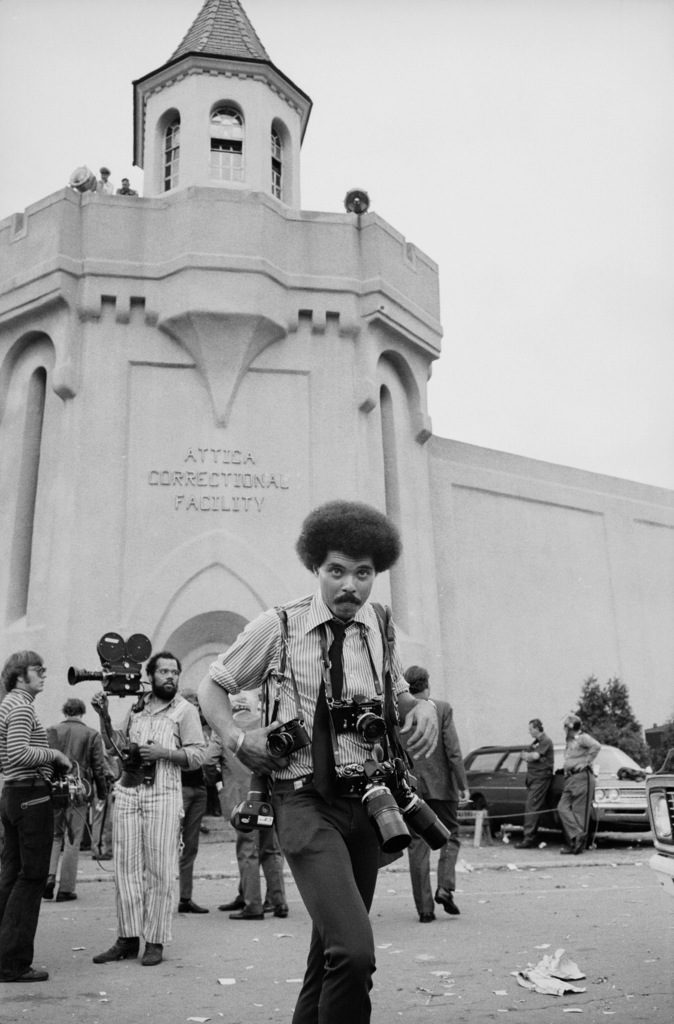

Photographer John Shearer on assignment outside Attica prison during a prisoner riot and uprising. (Photo by Bill Ray/The LIFE Picture Collection © Meredith Corporation)

During the four-day siege, many reporters and photographers tried to gain entrance to the facility. Yet the inmates controlling the situation only allowed in one photographer, John Shearer, a young staff photographer from LIFE magazine, who had documented the civil rights movement. They trusted him to accurately report their story. Shearer actually witnessed the September 13 attack on the prison by New York state police as they attempted to retake it on the order of Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Ultimately, 43 people were killed during the siege, including 11 hostages. The devastation on the last day left 89 people wounded, and other prisoners were shot or killed after surrendering.

Soon after the uprising, the McKay Commission, also known as the New York State Special Commission on Attica, investigated the events of September 1971 and the conditions that led to them, releasing a 514-page report in September 1972 based partly on interviews with inmates, corrections officers, and even Governor Rockefeller. The controversial report noted that the attack on inmates by the state police that ended the siege was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.

The Commission severely criticized the state’s handling of the event. Its findings also resulted in some reforms to the prison system, including the improvement of living conditions and the establishment of inmate grievance procedures.

The uprising also drew national attention to the issue of prison reform and its broader implications for the U.S. justice system as well as to the need for rehabilitation programs, educational opportunities for inmates, and the reconsideration of punitive approaches to incarceration.

Attica movie poster (2021)

There is much discourse on the subsequent interest in prison reform. For an overview of U.S. incarceration, take a look at the The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit organization that works to end mass incarceration and promote racial justice in the U.S. legal system. Mass incarceration is caused by several factors: an increase in the length of sentences for serious crimes, an increase in the number of crimes that lead to prison sentences, and the punitive law-and-order policies of successive presidents since Richard Nixon in 1968. The U.S. prison population largely comprises uneducated men under 40 from marginalized Black and Brown communities. The incarceration rate for Black men has nonetheless actually declined since 2006. In spite of this decline, however, Black Americans remain more likely to be imprisoned than their Latino and white counterparts and in 2020. The question remains: What is being done to reform and rectify this system of mass incarceration?

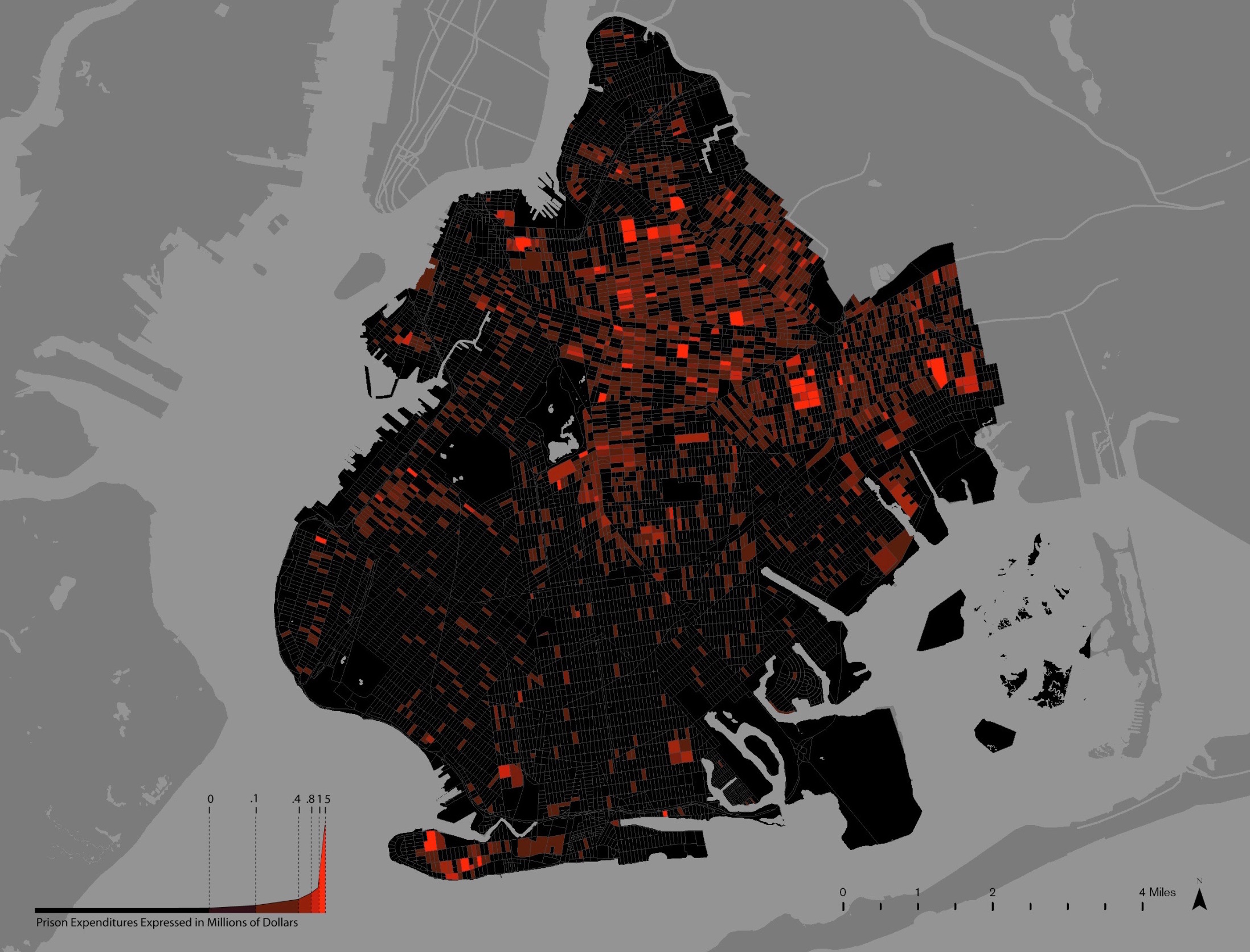

Prison Expenditures in Brooklyn courtesy of Million Dollar Blocks.

The Million Dollar Blocks project has used data-visualization imagery to clarify how five of the nation’s cities invest in incarceration rather than in individual lives and communities. The studies are concentrated in neighborhoods with high Black and Brown populations. Developed by the Columbia University Center for Spatial Research Lab and the Justice Mapping Center of the National Institute of Corrections, Million Dollar Blocks was the subject of a 2013 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The project visualized data on spending per capita in specific blocks and/or neighborhoods and revealed that millions of dollars are spent per city block on incarceration in prisons or jails, mainly for low-level offenses among low-income communities of color. There are established models for improvement, however. The Justice Reinvestment Initiative, for instance, has been practiced in more than a dozen states, including Maryland, Missouri, and Pennsylvania, and aims to reduce incarceration rates.

Another subject of reform is the school-to-prison pipeline. Terresa Moses is Assistant Professor of Graphic Design and Director of Design Justice at the University of Minnesota College of Design. She is also the Creative Director of Blackbird Revolt, a social-justice based design studio. Moses questions the effectiveness of educational systems, housing, jobs, and mental-health services that often fail to address the disparities and systemic racism faced by Black and Brown communities. She believes that public policy on policing and sentencing needs to be challenged to disrupt the system in which Black and Brown youths experience harsher treatment in schools and at the hands of law enforcement than others. Project NIA, founded by Mariame Kaba, author of We Do This, “Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice (2021), is a program that promotes restorative and transformative practices within communities. Such initiatives are critical to the remodeling of the criminal-justice system.

The Attica Uprising remains a crucial reference point in discussions about criminal-justice reform and mass incarceration. The event exposed long-standing issues that represented the experiences of many incarcerated people across the country: inadequate housing conditions and medical care and a lack of educational opportunities. Efforts along these fronts continue with varied success.

Some additional resources:

Attica Brothers Foundation, Attica is All of Us

Chicago’s Million Dollar Blocks

Design and Violence, Million Dollar Blocks at MoMA, New York

American Moments: John Shearer at The Capa Space

Mariame Kaba, Attica Prison Uprising 101: A Short Primer

Katy Groves, Attica Prison Uprising 101: Illustrations

Mariame Kaba Interview on Be Antiracist with Ibram X. Kendi

The Only Photographer Allowed at the Attica Prison Riot Remembers Four Days of Chaos

Fifty Years After Attica, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle

Stanley Nelson and Traci Curry Discuss Their Attica Film

John Shearer’s Photograph for LIFE