Travel to New York by Sea: From Steerage to Floating Palaces

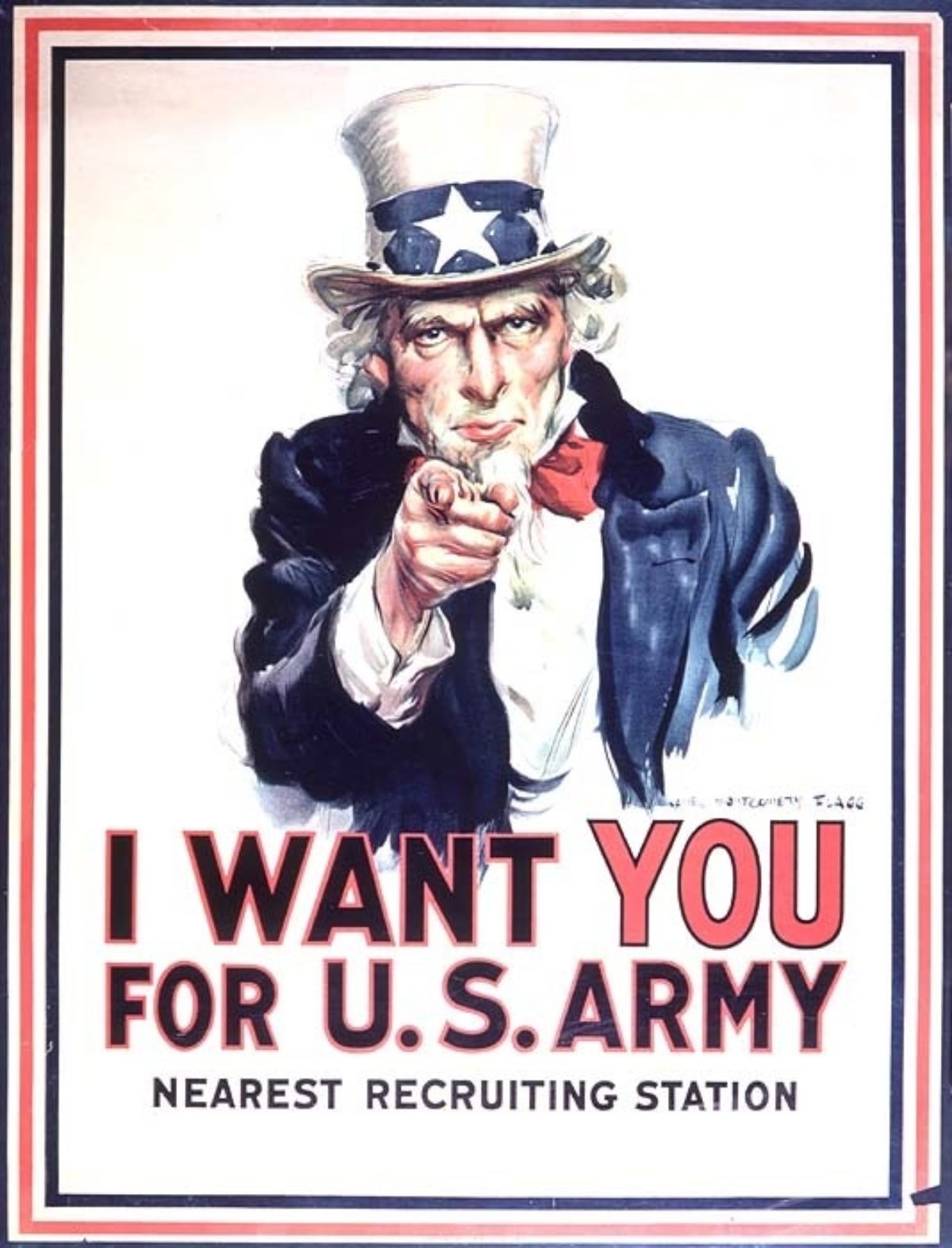

.The museum’s current exhibition, Wonder City of the World: New York City Travel Posters (on view through September 8) looks at the ways in which artists of many nationalities have packaged the genuine marvels of this great, rat-nibbled metropolis to travelers, immigrants, and tourists. The city appears from every angle in 75 posters advertising the ships, trains, and planes by which people have journeyed here since the 1890s, the decade in which these huge (mostly chromolithographic) compositions were first issued in significant numbers.

Those of us who have worked on the exhibition and catalogue (with a total of 180 posters) have our clear favorites among the vessels and contraptions. Nicho Lowry, the exhibition’s curator, for example, appears to prefer TWA’s Lockheed Constellation (which entered commercial service in 1946), often stopping on tours to admire its “dolphin-like fuselage.”

TWA/Etats-Unis (c. 1947), Frank Soltesz

Poster House Permanent Collection

While I can’t deny the appeal of “the Connie,” I’ve become quietly obsessed by the ships. Any shrink worth their salt would swiftly intuit that this is because my mother’s ancestors, like those of millions of other New Yorkers, originally came over from Eastern Europe on some hazardous, creaky watercraft; around 1900, in flight from menacing locals and assorted pogroms, they braved the dark, stuffy communal confines, nasty rations, and primitive sanitary facilities of steerage in the hope of reaching the promised lands of the Lower East Side and Brooklyn. This psychological surmise is probably validated by the fact that, for me, the least glamorous ship poster in Wonder City, that of the Red Star Line’s SS Westernland, an image mainly intended to appeal to the company’s large number of immigrant customers, remains the most fascinating.

The 1893 poster of the SS Westernland (launched a decade earlier), one of the earliest works in the exhibition, represents the important role played by the Red Star Line, a Belgian-American collaboration, in the transportation to the United States of more than two million immigrants between 1873 and 1934.

Red Star Linie/Antwerpen (1893), Carl Saltzmann

For before the undeniably racist Quota Acts of 1921 and 1924 severely restricted immigration, mainly from eastern and southern Europe, and allowed no entry at all from Asia, European steamship companies of every kind had made much of their revenue by transporting immigrants to Ellis Island. Necessity, often of the most desperate kind, was typically the main reason for such journeys. The poster focuses on the huge vessel and includes the Brooklyn Bridge (1883) and the Statue of Liberty (1886), a new and potent symbol of hope; however, it predates the skyline that would later become emblematic of the city.

The Westernland was the first Red Star Line ship to offer three classes of accommodation, and as on all these ocean liners, traditional social hierarchies, reflecting snobbery, racism, and a terror of contagion, were rigidly observed. In 1893, the year this poster was published, Irving Berlin, the future composer of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” and “White Christmas,” arrived in New York (from a shtetl in what is now Belarus) aged five on another Red Star Line ship, the SS Rijnland. Before embarking in Antwerp, his family, like the others in steerage, would have been subjected to a series of horrible indignities: their bags were sterilized in steam chambers and their clothes fumigated before the passengers themselves were forced to shower with vinegar and various chemicals. They then faced medical inspections that typically left two to four percent of ticket holders behind. (And they were greeted by a similar routine upon arrival at Ellis Island.)

Image courtesy of the Red Star Line Museum.

Not all immigrants escaping persecution were impoverished, of course. The great German-Jewish physicist Albert Einstein had been traveling on the Red Line since he arrived in New York in 1921 on the SS Rotterdam for the first of many American tours; he usually traveled first class and was welcomed with much jubilation wherever he landed. In October 1933, he disembarked in New York again, from this very ship, the Westernland, after renouncing his German citizenship and on his way to take up a position at Princeton.

Cunard White Star (c. 1937), Tom Curr

Poster House Permanent Collection

During the 1960s, my parents did honeymoon in relative style (well, in second-class) on the RMS Queen Mary, and Great-Aunt Myra, who married down into our family, swanned over to Europe, probably in first-class, on the SS France (relaunched in 1962). If we are playing this game, this might explain why I’m also captivated by the posters of some of the more celebrated ocean liners in the exhibition, especially those from the 1930s, when the shipping lines turned their attention to tourists, wealthy and otherwise. In 1935, for example, the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (known in the English-speaking world simply as “the French line”) launched its massive liner the SS Normandie (1935) and in 1936, the Cunard White Star Line’s RMS Queen Mary set sail, followed by its RMS Queen Elizabeth in 1938.

These vessels are described in the posters as magnificent beasts, almost as impressive in scale and beauty as the New York skyline behind them. Unlike those that promote travel to New York by train or plane, the posters issued by shipping lines are typically centered on their latest floating palaces in this way rather than on the city’s tourist sights. The majestic creatures promise a glittering world of giltwood paneling and Louis XIV furnishings or the latest in streamlined, gleaming Deco; lavish banquets; cocktails in curiously small coupes; and dancing in evening dress to live orchestras—much like a movie fantasy of Jazz Age Manhattan.

French Line (c. 1920), Richard Rummell

The SS France, however, seen here in a poster from around 1920, was the first of a series of spectacularly luxurious ocean liners launched by the French Line before World War I. She made her maiden journey in 1912, just five days after the sinking of her sister ship the SS Titanic. Like the Westernland, she was designed to house three classes of passengers (535 in first class, 440 in second, and 950 in third), and also relied for her revenues chiefly on immigration.

Here, the “Versailles of the Atlantic,” which could make the transatlantic crossing in just five days, almost conceals the Woolworth Building, the Park Row Building, and the Singer Building of the Manhattan skyline behind it. The France’s first-class passengers were mainly well-to-do Americans, and the 1912 brochure for the liner shows photographs of its lavishly appointed rooms, including “L’Appartement de grand luxe,” with its giltwood paneling based on that of the private royal apartments at Versailles. It also has two pages on the “Ventre du Monstre” (the Belly of the Beast), describing the alarming quantities of wine, fish, and beef that were loaded onto the ship before each crossing in preparation for the feeding of its grandest passengers. After its return to passenger service after World War I, the France offered only first- and second-class accommodation. And it added a branch of the Parisian department store Les Magasins du Louvre.

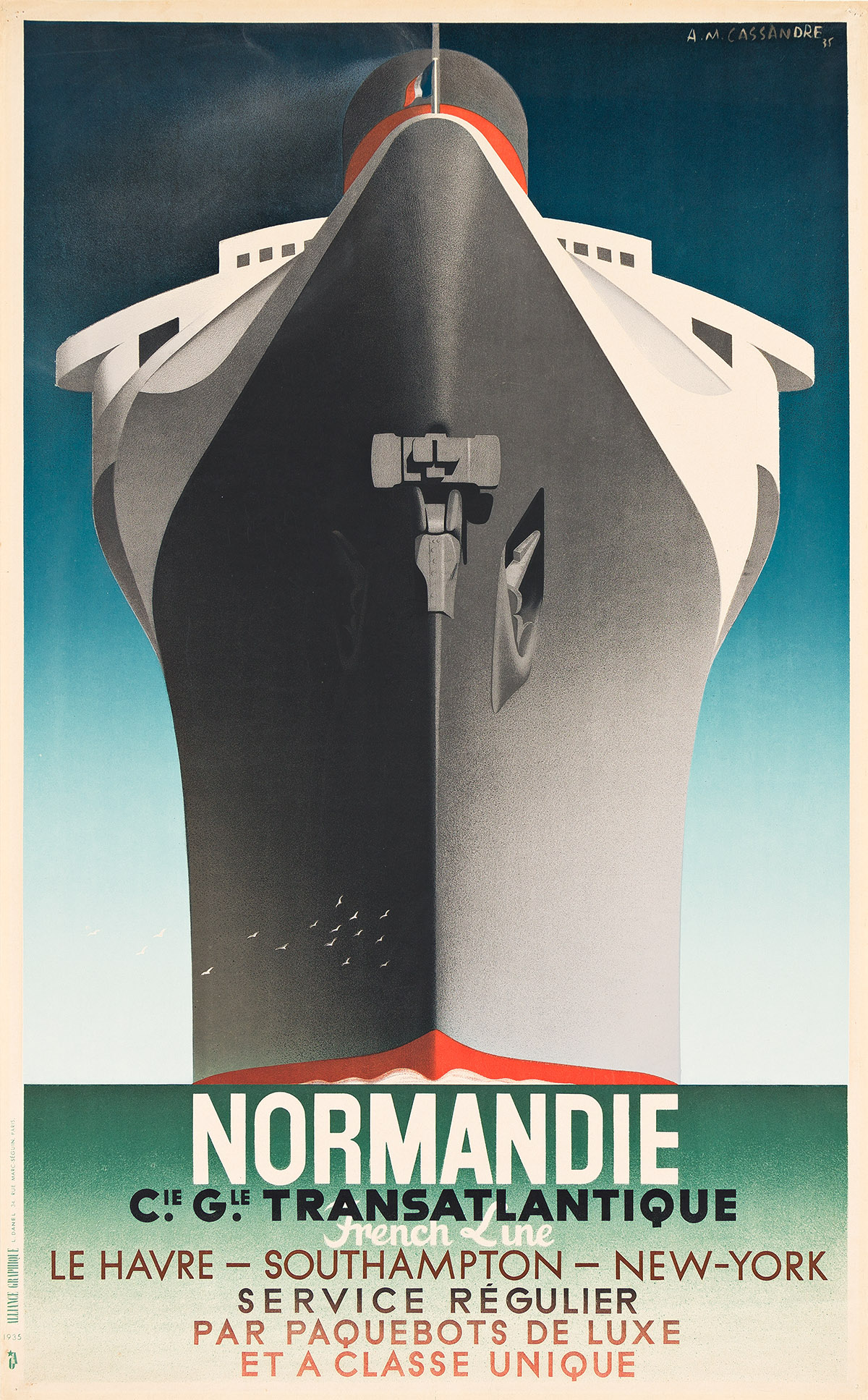

Normandie (1935), A.M. Cassandre

Image courtesy of Swann Auction Galleries

Following the acts of 1921 and 1924 restricting immigration, even the fanciest shipping companies had to reimagine their operations as means of ferrying Americans across the Atlantic for “pleasure cruises” and tourist trips. While in the decades before World War I, 750,00 to 1 million steerage passengers arrived in the United States each year, after 1924, this number was reduced to only 150,000 annually. The American middle classes of varying degrees of prosperity would now make up the bulk of their customers and the shipping lines launched advertising campaigns, including special posters displayed in travel agencies, on kiosks, and in public spaces to market their services to them.

On the increasingly modern and opulent ocean liners, steerage was gradually replaced by “tourist class,” sometimes known as “third class.” A French Line brochure for the new Normandie in 1935 addressed its message specifically to the American middle-class tourist of modest means, “To tired professors, to weary students, to all routine-bound jaded toilers,” pointing to the ‘irresistible appeal… of suave, effortless living in the age-old atmosphere of charming France.” (American tourists in general appreciated the unrestricted alcohol on European shipping lines like this one, especially during Prohibition between 1920 and 1933.) The majestic form of the Normandie, the most splendid and powerful of the great ocean liners of the 1930s, was immortalized by A.M. Cassandre in the poster he designed the year of its launch and was breathlessly promoted in the press and in international news reels.

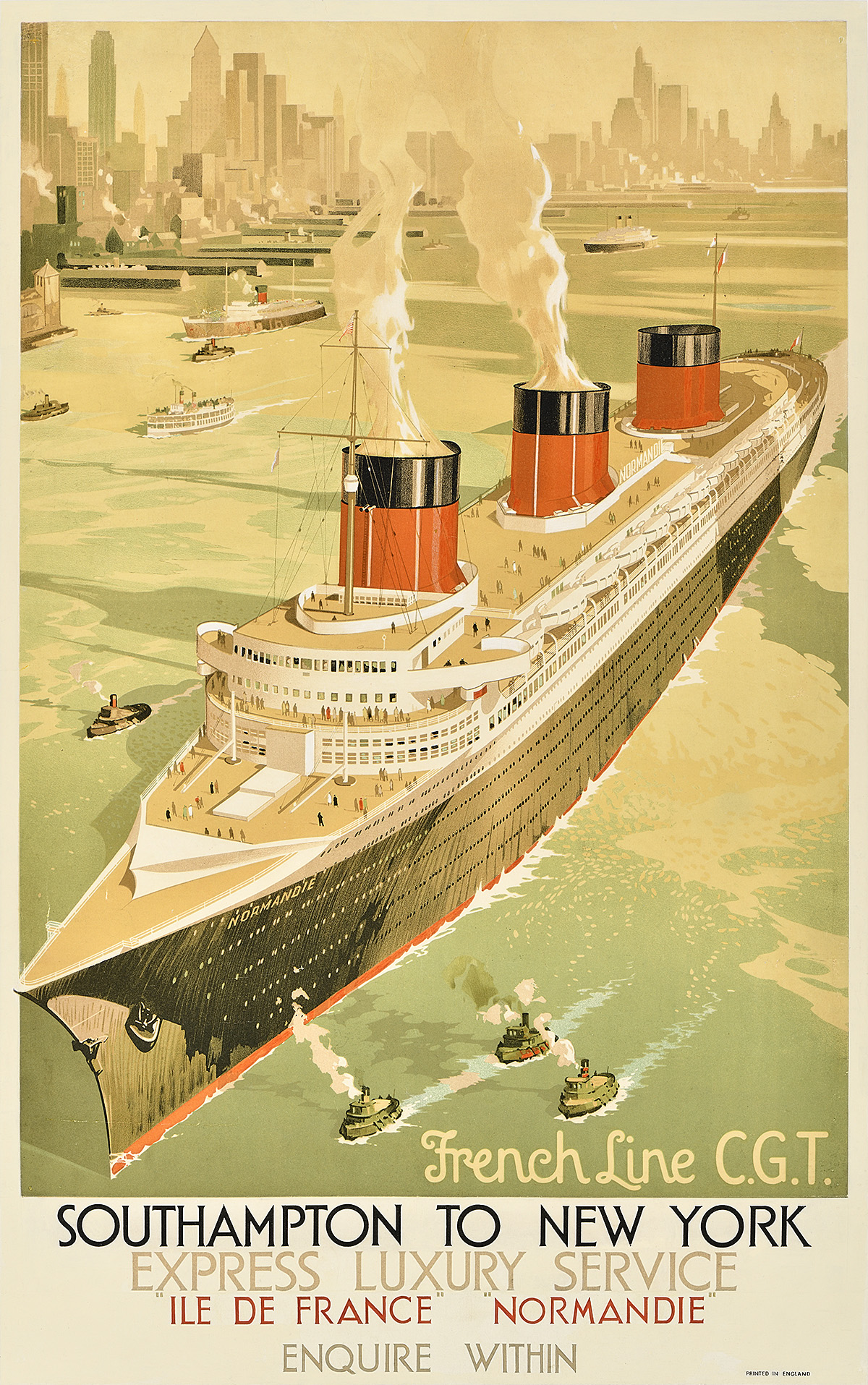

The ship is shown in another poster issued that year, based on an aerial photograph showing it sailing up the Hudson River to its berth at Pier 88 at Fifty-Fifth Street, one of the extra-large docks built by the city to accommodate the new superliners. The unknown designer has extended the very tip of the ship’s prow beyond the border of the image, suggesting that its massive structure can barely be contained within it.

French Line/Southhampton (1935), Designer Unknown

Poster House Permanent Collection

While it was privately owned by the French Line, the Normandie’s construction was subsidized by the French government to support the French craft industry during a period of economic depression—and intended as a monument to French artistry and technological progress. (It certainly helped that the ship was awarded the much-coveted Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic by a passenger ship on its maiden voyage—in a mere 4 days, 3 hours, and 14 minutes). The final product incorporated traditional styles filtered through the opulent, streamlined lens of Art Deco. The Grand Salon, for example, was decorated by a series of four gilded-glass murals showing fantasy vessels and mythological figures, designed by Jean Dupas and executed by Charles Champigneulle, while its floor was covered by the world’s largest hand-woven carpet, custom-made by Aubusson.

In addition to exceptionally sumptuous private cabins, the 848 first-class passengers could enjoy a theater, a library, a smoking room, a promenade deck with a winter garden and live exotic birds, a screening room, and the largest swimming pool ever built on a ship. For their children, there was a playroom and a dining room decorated by Jean de Brunhoff with Barbar the Elephant. In the first-class dining room, a modernist riff on both a Greek temple and on the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles (just longer), illustrious passengers like Marlene Dietrich, Fred Astaire (here he is arriving on the Normandie at Southampton in 1936), Ernest Hemingway, and Salvador Dali consumed exquisite French meals at tables set with specially designed Christofle silverware and serving pieces. In this interior space, with its mirrored glass walls designed by Labouret, softly illuminated by Lalique lighting fixtures, and concealed behind 20-foot-high bronze entrance doors by Raymond Subes, such passengers might have imagined themselves protected from both political and oceanic turbulence—and from the shabbier tourist-class passengers (some 450) also housed on the ship, at least some of them refugees from Hitler’s Germany.

The Normandie was in New York in September 1939 when war broke out in Europe, and it was impounded by the U.S. authorities. During her rushed conversion to a troop ship called the Lafayette in February 1942, she was destroyed by fire. (Some say sabotage….) Fortunately, some of her finest fixtures had already been removed and stored in a New York warehouse. Some of these were repatriated to France, and others are now scattered in public and private collections around the world. Surviving panels of “The History of Navigation” murals are in the Met’s collection (28 of them decorated the bar in the old restaurant), the Brooklyn Museum, and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh (along with Jean Dunand’s bronze and lacquer doors to the Normandie’s smoking room), for example, and panels still turn up on the art market.

If this sorry fixation continues, it’s only a matter of time before I find myself at the new Red Star Line Museum https://redstarline.be/en in Antwerp (housed in the very building from which the steerage passengers were “processed” before embarkation), in search of Einstein’s 1933 letter of resignation to the Prussian Academy of Science, written on Red Star Line stationary, and Irving Berlin’s piano.