Who Was Phoebe Snow?

.Who was Phoebe Snow? It’s one of those questions that keeps a museum cataloguer awake at night. In contemporary terms, she is the most annoying fellow passenger on a long train journey, her clothing elegant and pristine hour after hour as she serenely surveys the escalating chaos: fraught parents with toddlers who won’t stop licking the windows; students on their way home to the burbs listening to that relentless, tinny beat on whatever device; and a New York editor scrabbling in her voluminous purse, rank with the remains of an ill-advised tuna sandwich, for a lost ticket. My guess is, Miss Phoebe Snow was just as insufferable when she traveled before World War I on “The Road of Anthracite” (as the Lackawanna Railroad described itself) as its fictional ambassador and the icon of a hugely successful advertising campaign.

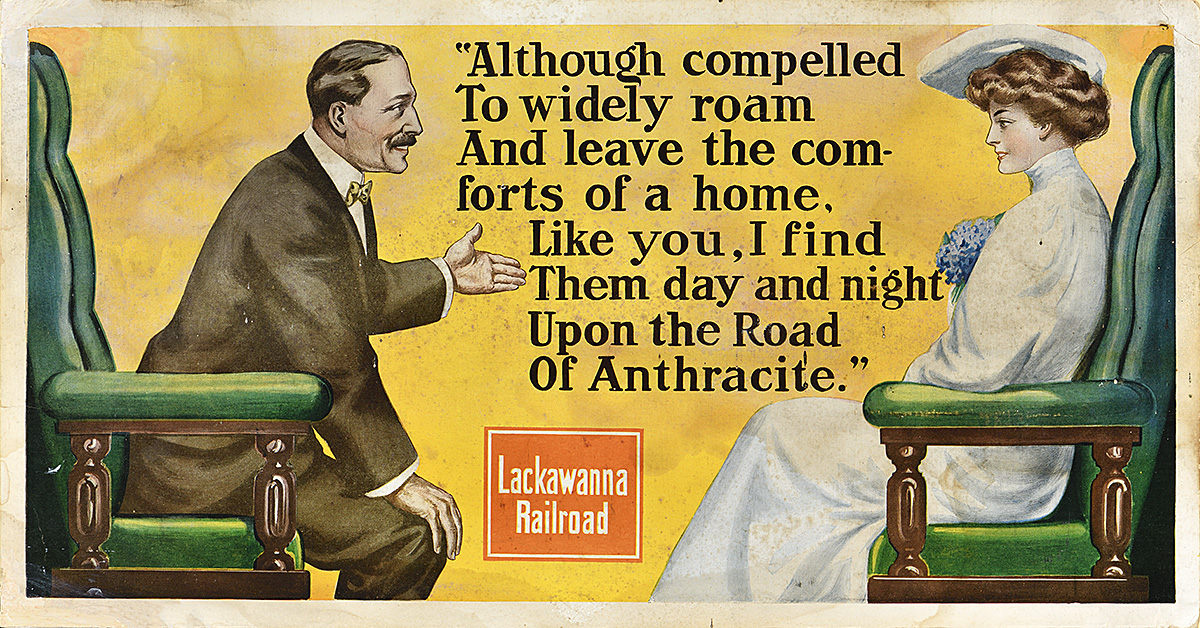

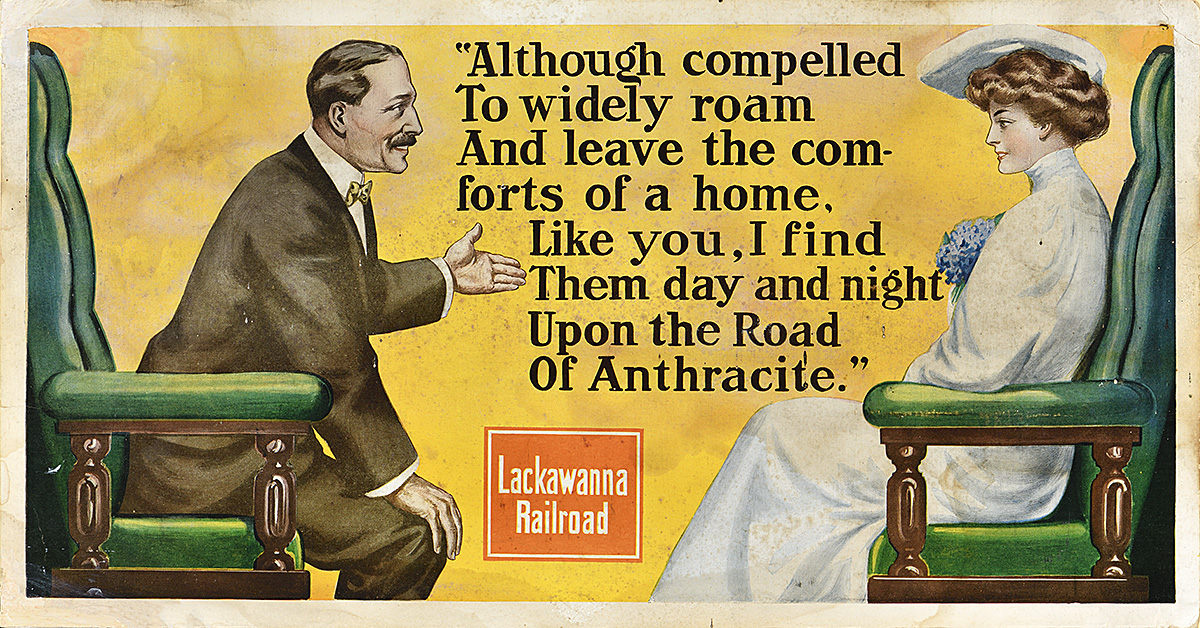

Lackawanna Railroad (c. 1910)

Poster House Permanent Collection

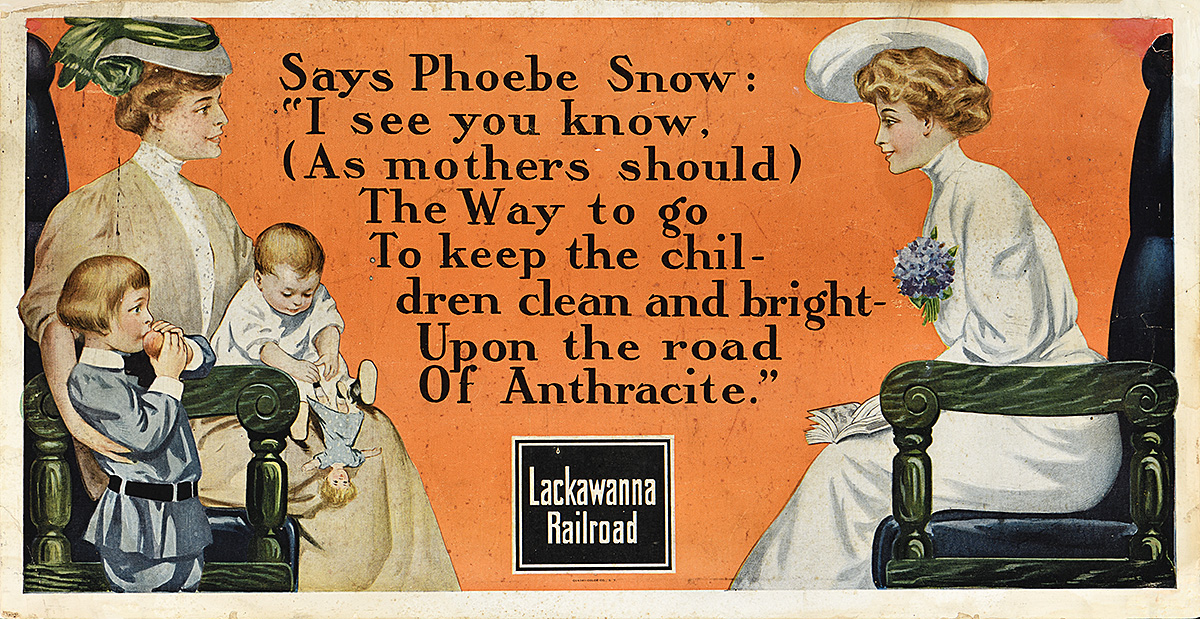

This tiresome woman, seen on the right in this train-car poster from around 1910 in her characteristic spotless white dress and corsage of violets, was invented by advertising pioneer Earnest Calkins for the Lackawanna Railroad in 1903 as part of a campaign to promote the cleanliness and safety of the passenger locomotives it ran between towns in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. All of them were run on sootless and virtually smokeless anthracite coal from the extensive Pennsylvania mines owned by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, as it was officially known, and which had been incorporated in 1851 mainly to transport the anthracite to the coal markets of New York City.

The original artwork for the refined Phoebe Snow was painted by Henry Stacy Benton and based on images of Marion Murray, a live model, who also embodied the fictional character in real life, photographed riding the trains and visiting towns on their route. Phoebe Snow, described as “a Young New York socialite and a frequent passenger of the Lackawanna,” played a critical role in reassuring potential passengers that rail travel did not have to be the filthy and hazardous undertaking it generally was at this time. (“On railroad trips/No other lips/Have touched the cup/That Phoebe sips.”) The Road of Anthracite, suggested the numerous posters in the series, allowed well-dressed passengers like Miss Snow, whose “gown stays white/from morn till night” and the gentleman opposite her, praising the service in the rather leaden rhyming couplets that feature in all of these in-car posters, to travel in the kind of clean, safe, and comfortable environment they were used to, complete with white linens in the dining car and electric light. Notably, this poster also implies that even a respectable upper-class woman like Phoebe Snow might travel unchaperoned on such trains without moral risk. While the businessman leans forward, gesturing to make his point, the chronically prim Miss Snow remains upright in her upholstered chair. They might almost be conversing in a drawing room.

Lakawanna Railroad (c. 1910)

Poster House Permanent Collection

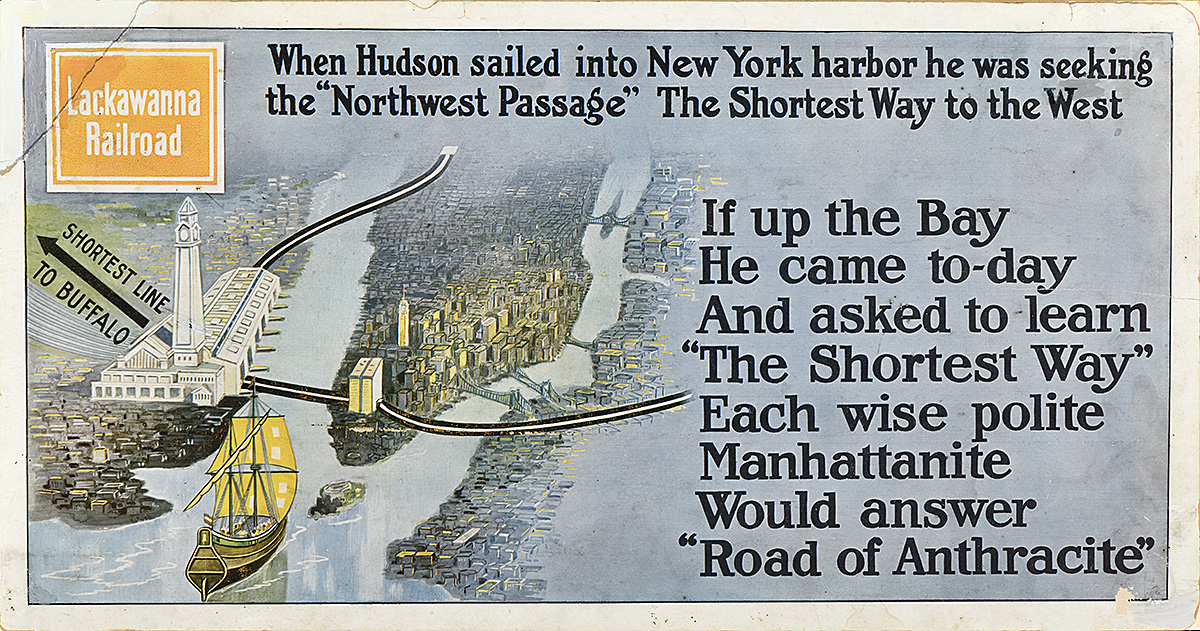

This poster from the campaign, unusually, does not feature Phoebe Snow but suggests that Henry Hudson, when he sailed into New York harbor in 1609 in search of the Northwest Passage, would surely have used the Lackawanna Railroad for the rest of his journey if only it had not been invented centuries later. Or something to that effect. It shows a bird’s-eye view of the southern part of Manhattan and the bridges connecting it to the other boroughs. On the left, an arrow points north to Buffalo (where New York socialite Phoebe Snow often bravely ventured) from the line’s beaux-arts terminal in Hoboken, New Jersey, built in 1907.

Americans certainly needed convincing that rail travel was a good idea at this time. Thousands of passengers and railroad workers were killed or injured on American trains between 1902 and 1911. Even if they survived the journey intact, passengers typically disembarked covered either in the ash of wood-burning steam engines or in the soot from the clouds of smoke emanating from trains powered by bituminous coal. In addition to convincing Americans of the cleanliness and safety of anthracite-powered trains, the glamorous Phoebe Snow was also designed to distract them from the frequent news of miners’ strikes, child workers, and mining disasters emerging from the Pennsylvania coal regions; it is hardly coincidental that the campaign was launched the year after the Anthracite Coal Strike in Pennsylvania in which President Teddy Roosevelt felt compelled to intervene after 163 days. (“Says Phoebe Snow: “The miners know/That to hard coal/My fame I owe,/For my delight in wearing white/Is due alone to Anthracite.”) Lewis Hine was actually hired in 1908 by the National Child Labor Committee to photograph the “breaker boys” paid a pittance to separate by hand impurities from anthracite coal in the Pennsylvania mines. After an accident involving these child workers at the Chauncy Colliery in January 1911, he sent a clipping from a newspaper to the committee, and in April of that year, a fire broke out at the Price-Pancoast Mine in Throop, Lackawanna County, resulting in the deaths of 72 miners and one rescue worker. It was one of the deadliest mining incidents in American history.

Lakawanna Railroad (c. 1910)

Poster House Permanent Collection

As she circumnavigated her East Coast territory in her white dress, spouting her promotional verses, Phoebe Snow became something of a celebrity. In 1903, the year she was invented, Thomas Edison’s new motion-picture company even produced a short silent film, A Romance of the Rail, parodying the campaign. At a public appearance in Binghamton, New York, in 1904, Phoebe was greeted by ten thousand fans; she also inspired postcards, fashions, romance stories, and board games (there is one from 1909 in the New York Historical Society). Phoebe Snow disappeared with the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917 when anthracite was banned for use on passenger trains and diverted to the war effort. She was reintroduced during World War II, however, dressed in a patriotic uniform, as the line sought to revive its fortunes; in 1949, it even renamed its premier passenger train after her but the campaign ultimately faded along with the anthracite industry.

Here is Phoebe again during her pre-World War I heyday in classic form: this time, the apparently childless and perpetually unbesmirched Phoebe leans forward to address her fellow passenger, not a morally alarming, strange man this time but a mother traveling alone with two tiny children. The charming lady in white does not offer practical help, however, but patronage, congratulating the mother in those dreaded rhyming couplets for keeping her progeny so nice and clean on a long train journey. No wonder the mother barely summons a genteel smile as she clutches her infants closer.

Now you have at least some idea about Phoebe Snow, I can only recommend that if you encounter anyone resembling this once-celebrated personage on a long train journey, you swiftly decamp with your festering tuna sandwich to another car.