Posters in Protest

Introduction

In 2019, Poster House opened its first show sourced entirely from the museum’s permanent collection.

This exhibition, 20/20 InSight: Poster from the 2017 Women’s March was a powerful look at the unique ways Americans protest, as told through the lens of posters collected from the 2017 Women’s March. The march emphasized that protesting is part of American culture and is an essential expression of our constitutional rights.

The posters in the collection span the subjects of Women’s Rights, Climate Change, Immigration, LGBTQ+ Issues, and, of course, #BlackLivesMatter. The incorporated graphics and poster images have been carried through generations of marches, rallies, and grassroots action. Today’s demonstrators also display symbols from poster history, borrowing the power of past ideology while crafting new meanings.

Over the next few weeks, we will be highlighting five historic protests and some of their posters. These protests date back more than 100 years, their posters indicating that we are still demonstrating for the same struggles today.

July 28, 1917: The Negro Silent Protest Parade

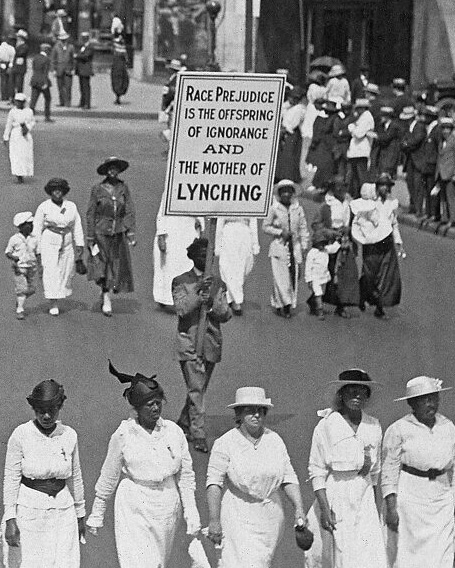

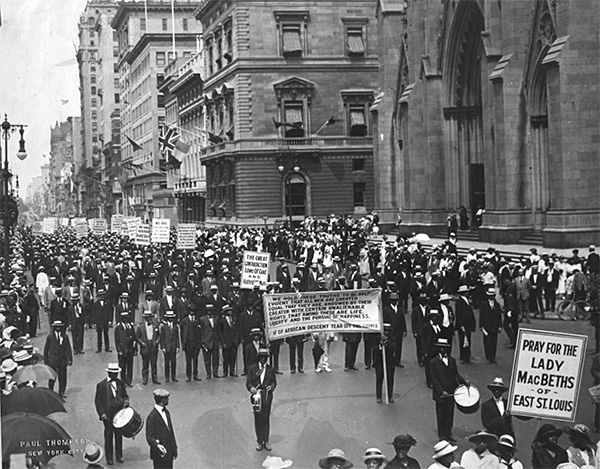

The Negro Silent Parade, Fifth Avenue, New York City. Photo credit: Paul Thompson

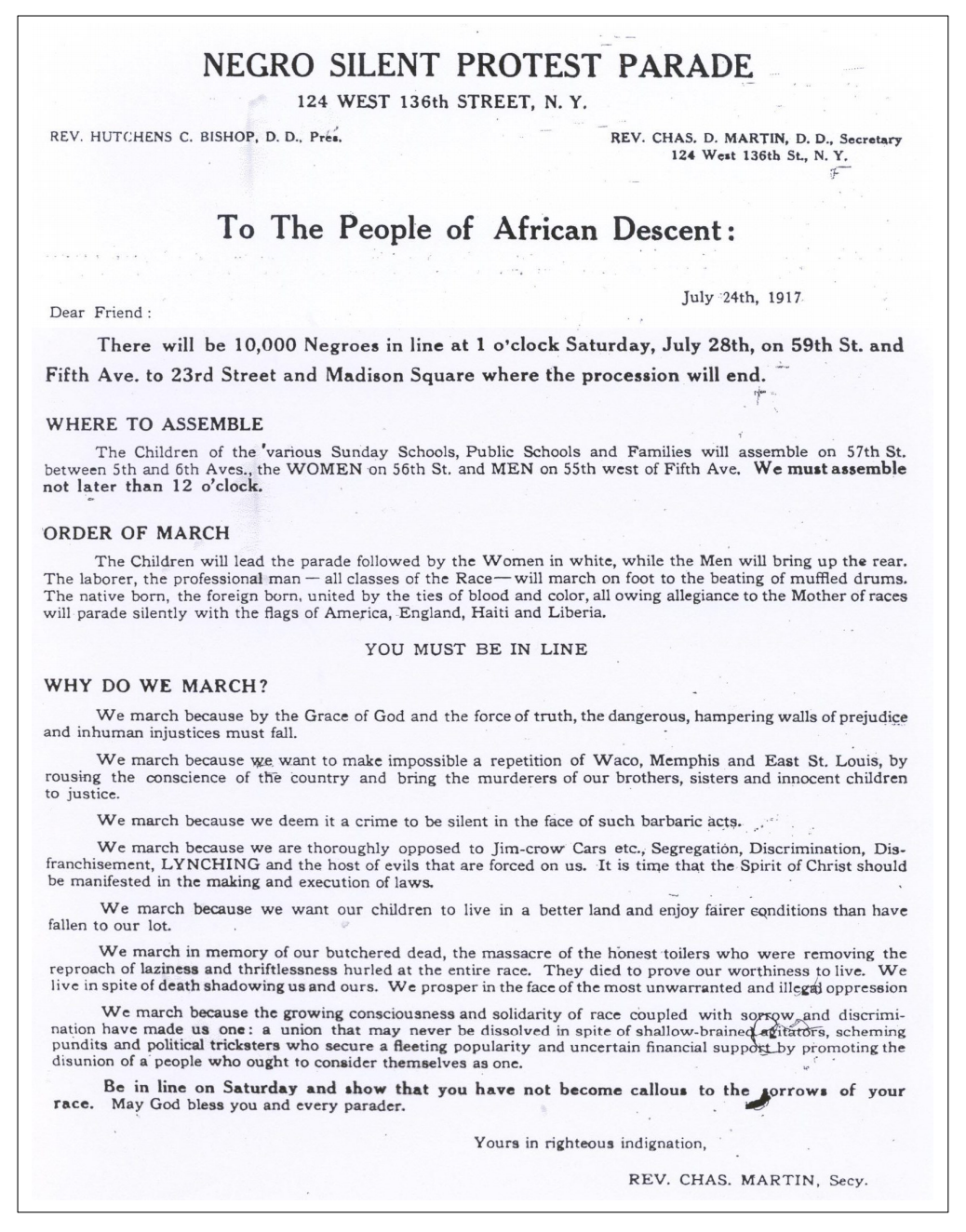

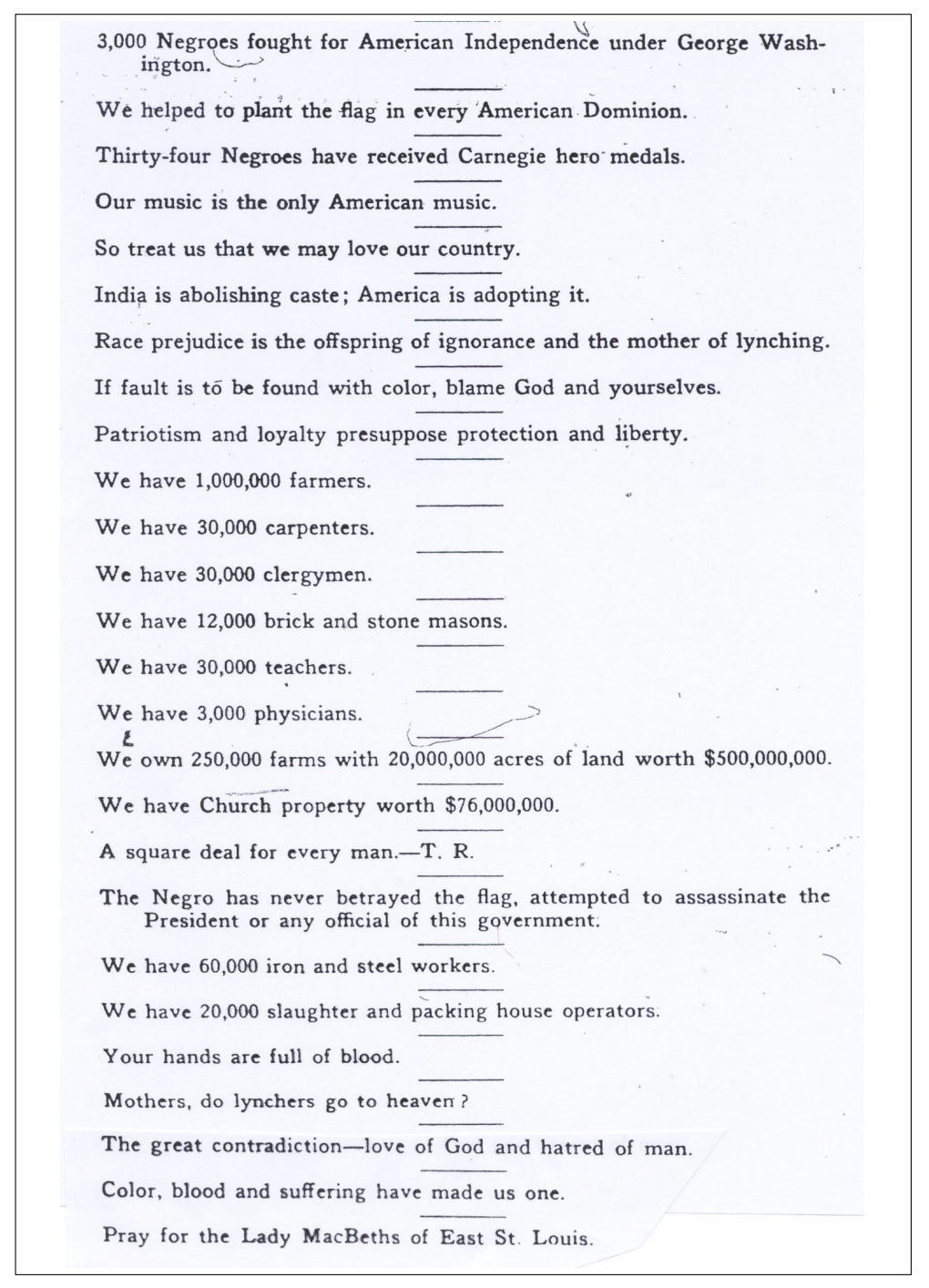

NAACP Silent Protest Parade, flyer, July 1917

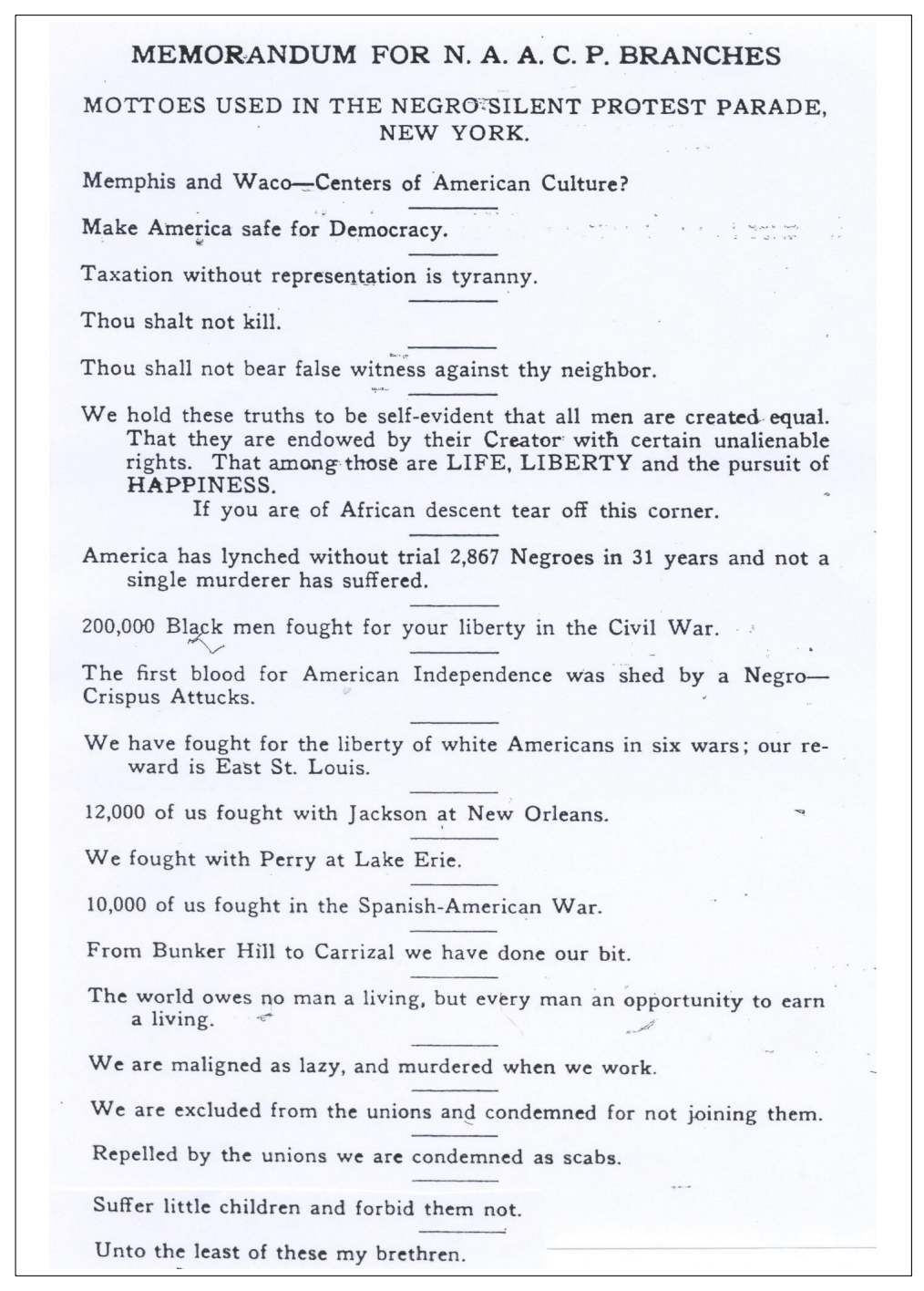

NAACP Silent Protest Parade, memo, July 1917; Part 1

NAACP Silent Protest Parade, memo, July 1917; Part 2

From late May to early July of 1917, there were brutal lynchings of African Americans by white mobs in Waco, Memphis, and East St. Louis, Illinois. In response to this violence, the NAACP organized a silent protest parade that led 10,000 African American women, children, and men to march down New York City’s 5th Avenue in support of equity. Paraders, including Black Boy Scouts, handed out leaflets explaining why they marched:

“We march because we want to make impossible a repetition of Waco, Memphis, and East St. Louis by arousing the conscience of the country, and to bring the murderers of our brothers, sisters, and innocent children to justice…We march because we want our children to live in a better land and enjoy fairer conditions than have fallen to our lot.”

The writing in the leaflet ends with the phrase “Pray for the Lady MacBeths of East St. Louis.” This was especially written and made into a placard to allude to the instance of white women in St. Louis pulling Black women onto the street, stripping them, and beating them with their shoes.

Ida B. Wells, acclaimed for her writing and investigation of lynchings, travelled to East St. Louis on July 4 to document the massacre of her people.

History has devastatingly repeated itself as we approach the 103rd anniversary of the Silent Protest Parade. In the aftermath of the murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd, we find ourselves in solidarity, yet again, fighting for equality.

Critique of the language used to describe Black women has allowed us to reconsider how we discuss strength and fear. When considering the work of Ida B. Wells, it is important to note that investigating lynchings and murders was dangerous and life-threatening, especially during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The word “fearless” suggests that the efforts of Black women defy natural human capabilities despite the adversity, trauma, and sadness that Ida B. Wells was subjected to while partaking in physical and emotional labor. Language around the labor of Black women, both historically and in the contemporary, should acknowledge realistic emotions that humanize their experiences.

Listen

The Silent Protest Parade (Bowery Boys) 39:49

Watch

This Week in Black History: The Silent Parade (Kiss 104 FM) 1:09

Lecture on Urbanization and Migration (Yale University) 42:59

Bloody Island: Race Riots of 1917 (Thomas Gibson) 52:03

Read

Remembering the NAACP Silent Protest Parade (Hyperallergic)

These African-American women helped in World War I (Share America)

Brief History of Black Women in the Military (The Women’s Memorial)

Learn More

Dec 1, 1955–Dec 20, 1956: Montgomery Bus Boycott

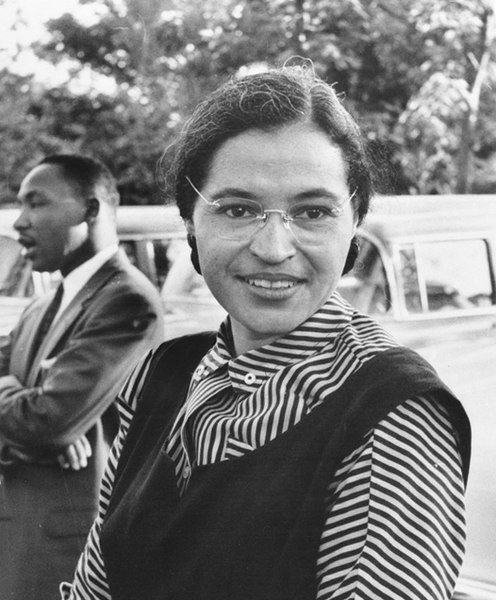

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks was a civil rights activist, best known for her work with the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955–1956.

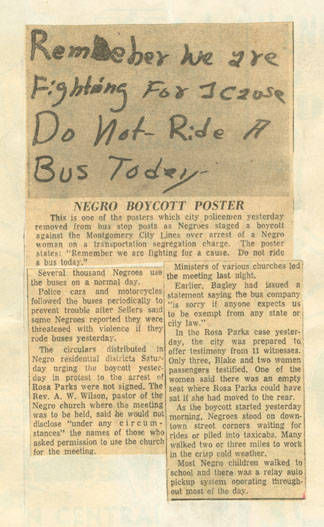

A poster encouraging black residents of Montgomery to boycott the city's buses. Photo courtesy: Alabama Department of Archives and History

An estimated 12,000 protesters marched in Newark on May 30, 2020. Photo credit: Jeenah Moon/Reuters

The scene outside the Barclays Center when an MTA bus driver refused to drive arrested protesters on behalf of the NYPD. Photo credit: Jane Kuntzman

Collective action continues to define the civil rights movements of today.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a collective, coordinated act of protest against a corrupt system of segregation. Despite what the textbooks say, Rosa Parks—the face of the boycott—was not just a tired seamstress. She was a trained activist, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott was neither her first protest nor her last. Following her refusal to give up her seat and subsequent arrest and fine, the Black community rallied around her.

Rosa Parks isn’t the only woman who played a crucial role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Jo Ann Robinson (head of The Women’s Political Council, a Black women’s organization focused on civil rights) bolstered the boycott by mobilizing the Council and others to distribute more than 50,000 flyers urging for Montgomery’s Black community to stop using city buses in protest of their racist practices.

The result was a boycott in which all Black people were walking, carpooling, and using Black-owned transportation services instead of the bus system. Today, we continue to see transportation playing a vital role in protest. Bus drivers in New York City and Minneapolis have refused to transport arrested protestors, and civilians using social media to offer safe means of transportation to their comrades.

It took 381 days for the Montgomery Bus Boycott to end. We stand in solidarity with those who are protesting—no matter how long it takes for change to come.

Listen

Watch

Montgomery Bus Boycott (PBS Project C) 34:57

Teaching About the Montgomery Bus Boycott (Zinn Ed Project) 15:00

Read

Montgomery Bus Boycott (MLK Institute at Stanford University)

The Truth on Rosa Parks (SPL Center)

Transportation Protests: 1841 to 1992 (Civil Rights Teaching)

Women’s Political Council (WPC) of Montgomery (MLK Institute at Stanford University)

Montgomery Bus Boycott—Facts, Significance & Rosa Parks (History Channel)

Jo Ann Robinson: A Heroine of the Montgomery Bus Boycott (NMAAHC)

Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (Book)

The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis (Book)

Learn More

Aug 28, 1963: March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

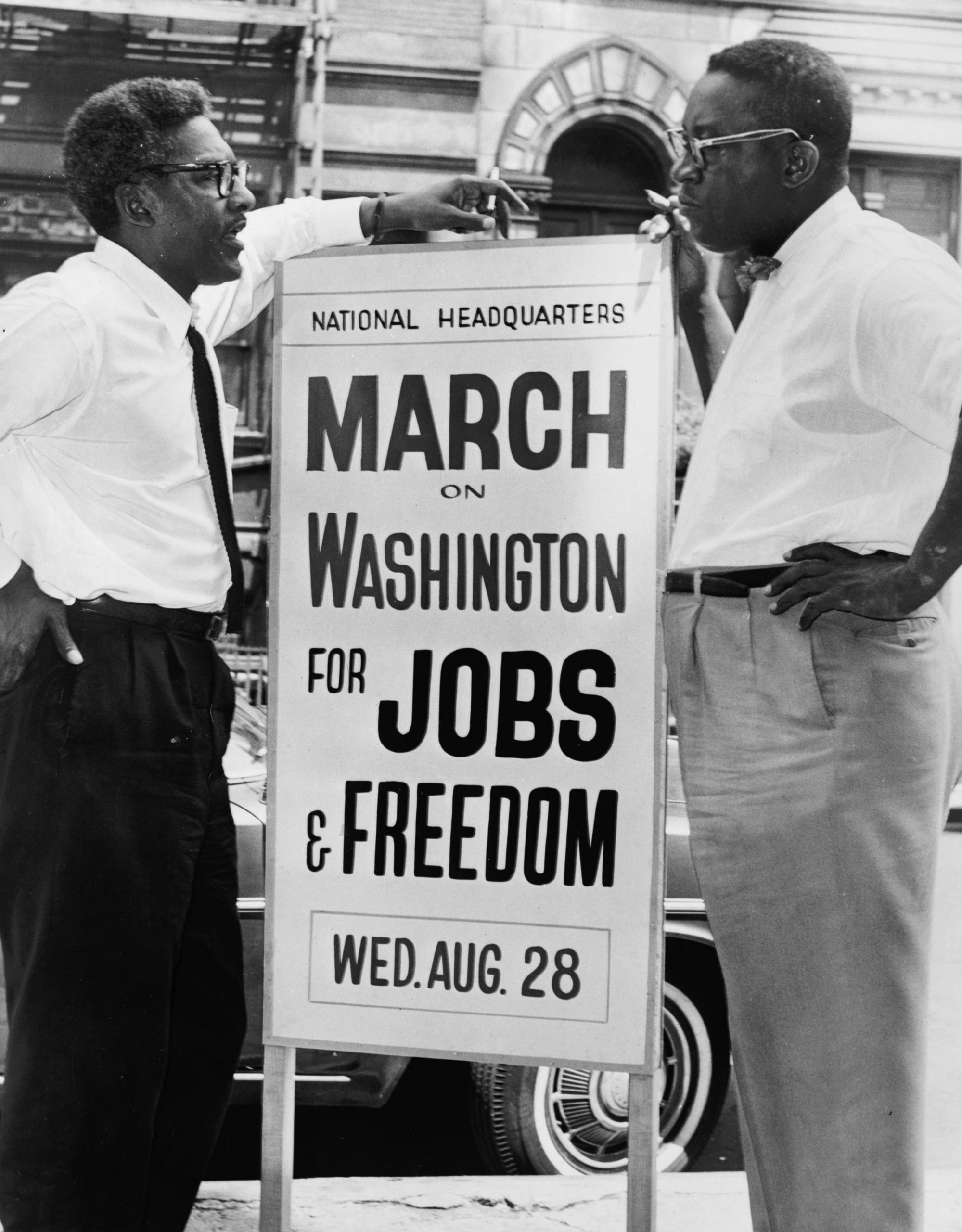

Civil Rights supporters at the March on Washington. Photo credit: Warren K. Leffler/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In front of 170 W. 130th Street, March on Washington, l to r, Bayard Rustin, Deputy Director, and Cleveland Robinson, Chairman of Administrative Committee. Photo credit: O. Fernandez/World Telegram & Sun

Black Lives Matter protesters rally in front of a building with the words "Black Lives Matter" projected on it. Photo credit: Colin Lloyd/Pexels

Marches continue across the U.S. and internationally in support of Black Lives Matter. Photo credit: Davon Michel/Pexels

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place on August 28, 1963, and is one of the largest Civil Rights rallies in American history, drawing a quarter of a million people to the nation’s capital. The purpose of the march was to draw attention to the political, legal, and social inequalities that African Americans still faced a century after emancipation. Pioneered by labor leader A. Phillip Randolph and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, the march was the collaborative effort of many different civil rights groups, religious organizations, and labor rights unions.

Today, we know that it was the unsung heroine, Anna Arnold Hedgeman, who was responsible for convincing Randolph and Martin Luther King Jr. to join forces—and for making sure that there was at least one woman, Daisy Bates, speaking that day. It was also at this march that Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his transformative “I Have a Dream” speech. Fifty-seven years later, we find ourselves still having to march against the discrimination and violence that Black people experience regularly in America. Will it be two centuries before our equity efforts make equality a reality?

Listen

The March on Washington At 50: The Inspiring Force of ‘We Shall Overcome’ (NPR) 8:00

How the March on Washington Worked (Stuff You Should Know) 46:00

Watch

March on Washington History (produced by NMAAHC) 18:00

The March by James Blue via The Motion Picture Preservation Lab, 1964 (US National Archives) 33:00

King Leads the March on Washington (History Channel) 3:00

Read

An Oral History of The March on Washington (The Smithsonian)

Posters for Change: Tear, Paste, Protest (Book)

Voices from the March on Washington by J. Patrick Lewis, George Lyon (Book)

Learn More

Mar 7–Mar 25, 1965: Marches from Selma to Montgomery

“We march with Selma!” demonstrators march in Harlem, March 1965. Photo credit: Stanley Wolfson/WT&S/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (LC-USZ62-135695)

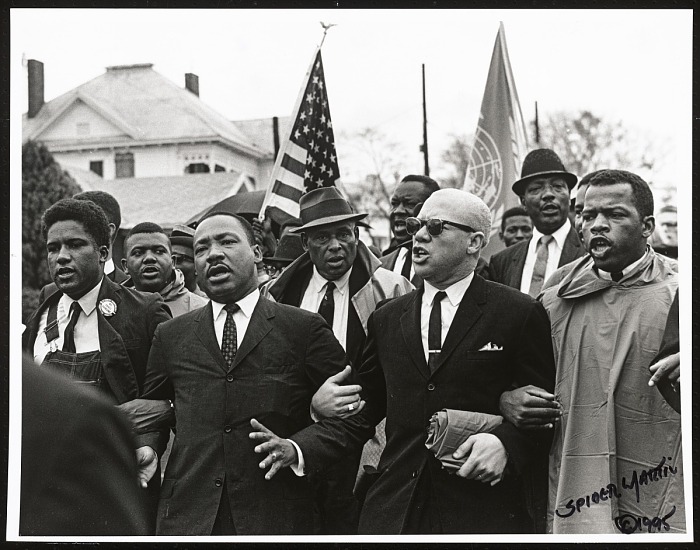

A photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. arm-in-arm with fellow Selma to Montgomery marchers. Photo credit: Spider Martin/Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture © 1965

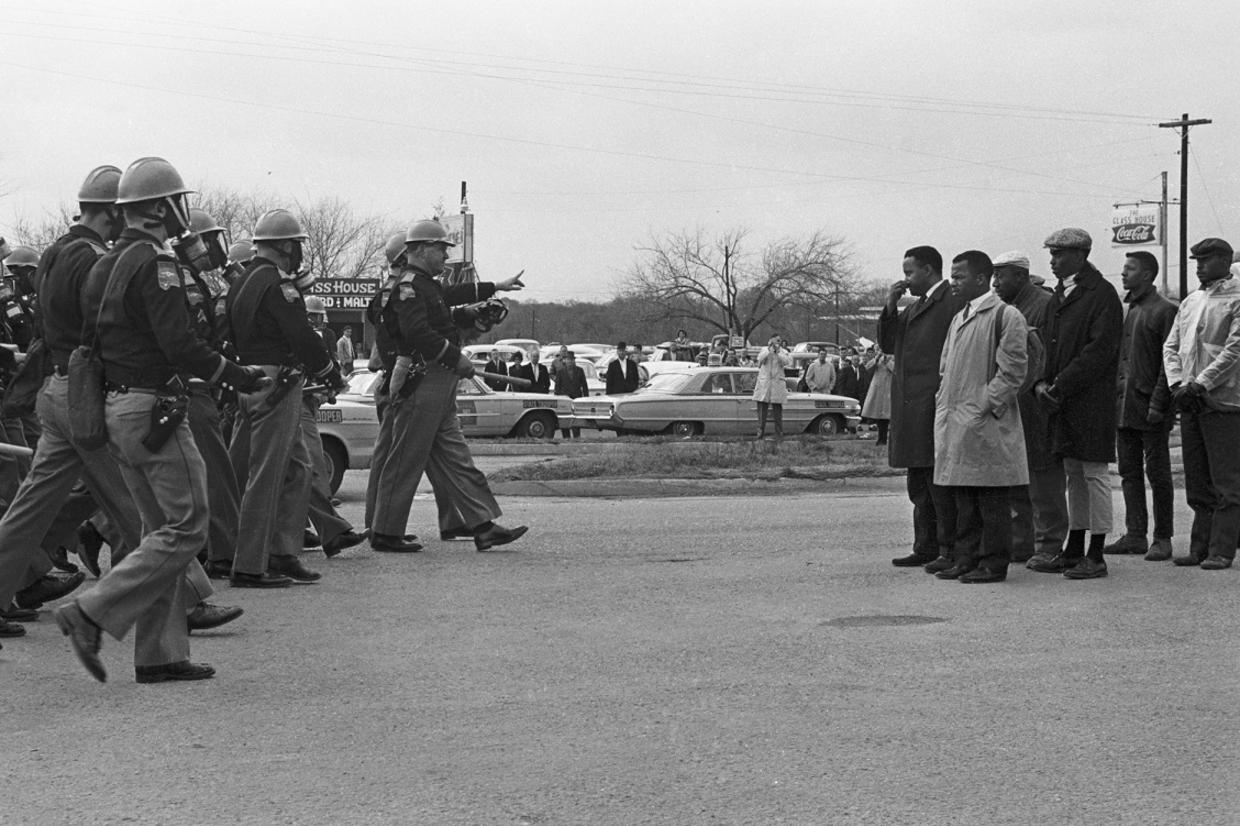

Local police and state troopers walk towards the Selma marchers, including John Lewis, moments before the acts that led to the date being immortalized as "Bloody Sunday." Photo credit: Spider Martin/Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture © 1965

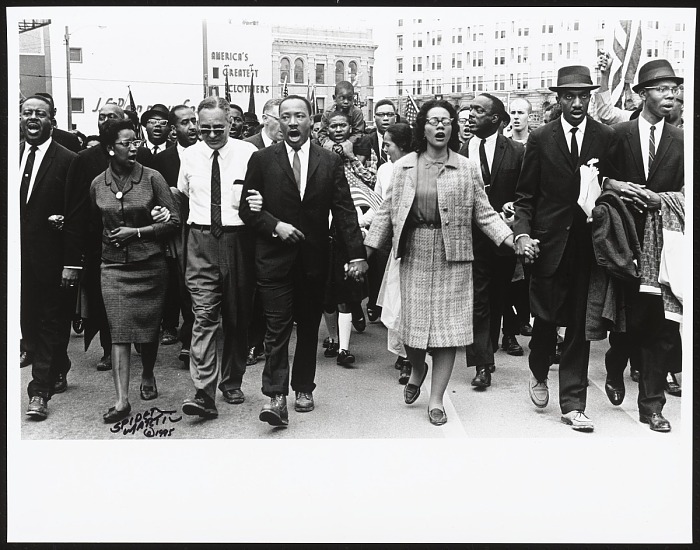

Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King walk with other demonstrators as the march finally enters Montgomery. Photo credit: Spider Martin/Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture © 1965

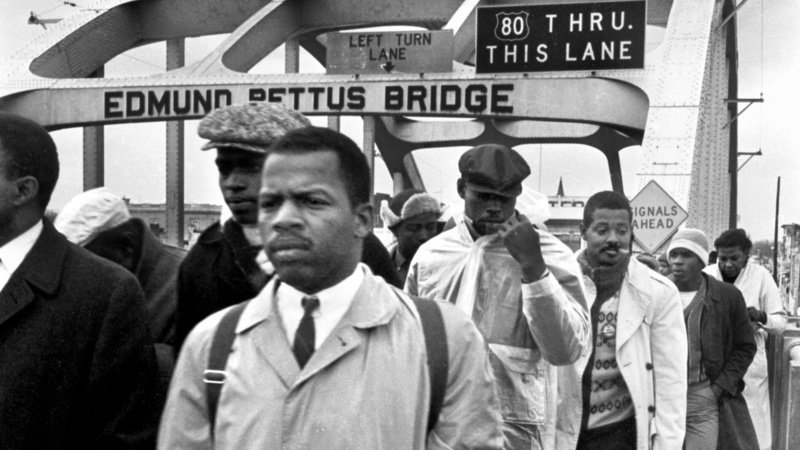

John Lewis—in his iconic coat—walks across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the first attempted march to Montgomery, AL from Selma. Photo credit: Spider Martin/The Birmingham News

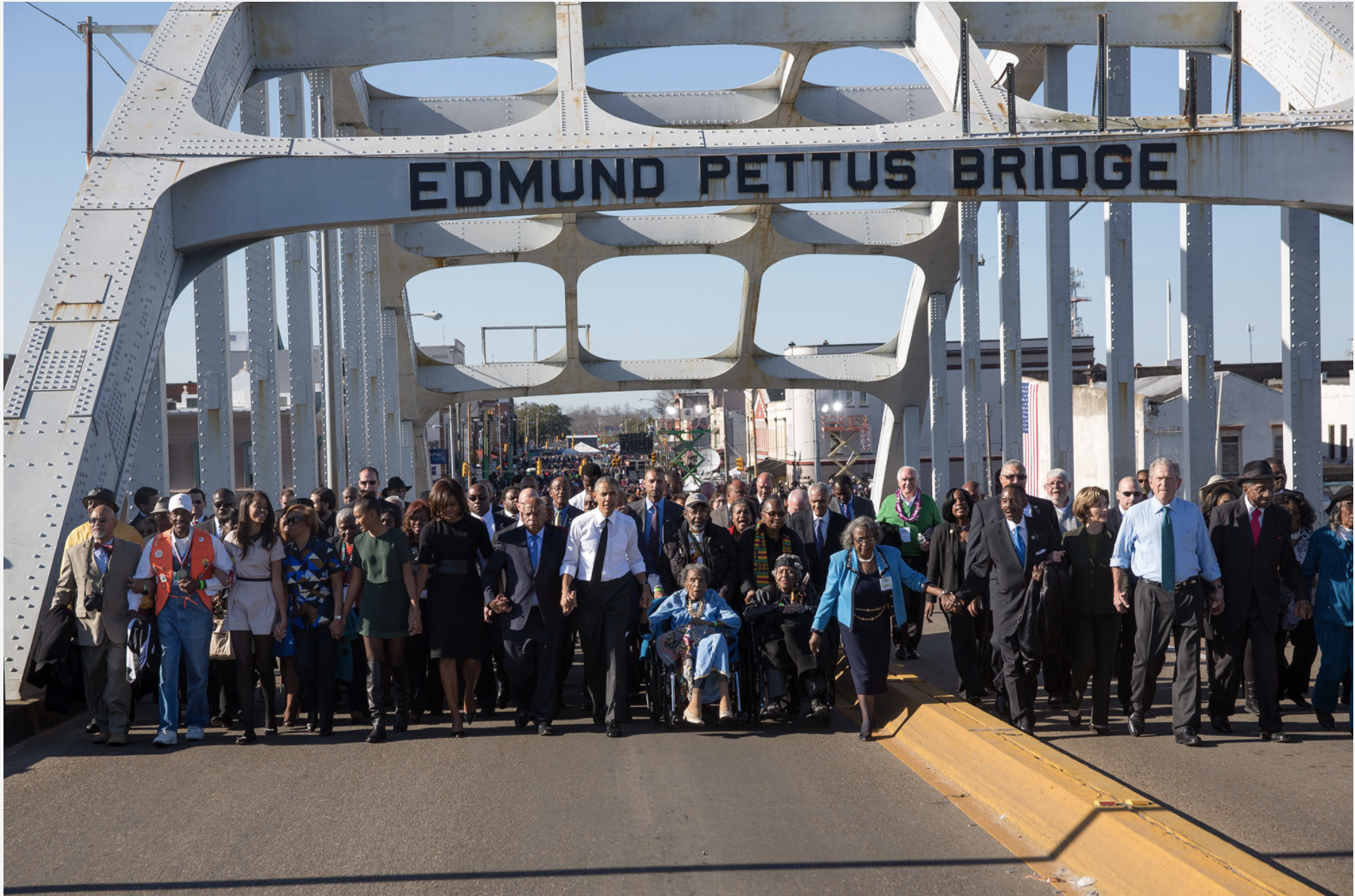

Original marchers from Bloody Sunday and the other marches to Montgomery honor the 50th anniversary of the protests with President Obama and his family. Photo credit: Lawrence Jackson/Official White House Photo

In March 1965, there were three marches along the 54-mile highway from Selma, Alabama to Montgomery, the state’s capital. These demonstrations were organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and Dallas County Voters League (LDC) to peacefully protest the repressive voting policies in the state that were disenfranchising African American citizens from voting in elections.

After Emancipation, Southern governments put in place active measures to ensure segregation and minimization of the rights of Black citizens. In order to vote, residents had to pay a poll tax and pass a literacy test demonstrating comprehensive knowledge of the constitution. Enacted and enforced by local leaders, regulations like these ensured most Blacks would be kept out of politics and voting. By 1961, 57% of Dallas County was Black, with Selma acting as the “unofficial economic, political, and cultural capitol” of the western portion of Alabama’s Black Belt. Of the 15,000 Black individuals old enough to vote in that county, only 130 were registered. While there were more significant Back majorities in the counties surrounding Selma, there were also many counties where not even one Black citizen was registered.

Following Brown v. Board of Education and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the NAACP was under attack and thereby forced to operate largely underground. This led to collective organizing by other African American activists and nonviolent organizations beginning with the Dallas County Voters League, soon joined by SNCC and the SCLC. In January 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. added his voice to the voting rights campaign that had begun in Selma. Within a month, young deacon and activist Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot following an evening march in Marion, where the local police and Alabama state troopers violently attempted to break up the otherwise peaceful demonstration. He would die eight days later.

After Jackson’s death, activists came together to march from Selma to Montgomery. At the head of this march were SCLC leader Hosea Williams and SNCC leader John Lewis. As they crossed the Edward Pettus bridge, the protestors were met with a police blockade of state troopers and local law enforcement led by Sheriff Jim Clark and Major John Cloud. Marchers were asked to disperse, and, when they did not, the resulting documented violence was so outrageous that it would be forever known as Bloody Sunday. The horrific footage from this encounter was broadcast across the country, leading to national outrage.

Dr. King—who had been in Atlanta at the time—reacted to these atrocities by calling on people from all over to join in a second attempt at the march from Selma. Despite President Lyndon Johnson asking King to call off the demonstration until a federal court order could be put in place to protect the marchers, King and 2,000 protestors met on the Pettus bridge that Tuesday and held a prayer before returning to Selma. This peaceful demonstration went off without incident.

Johnson spoke with Alabama’s Governor Wallace about the threats of violence against the protestors. At the same time, he also introduced legislation for voting rights that ensured universal suffrage. On March 21, the Selma demonstrators began their march with protection by state and federal law enforcement. Over the next few days, the original 300 protesters grew to over 25,000 people by the time they reached Montgomery. On that final day, Dr. King addressed the people in his now-iconic speech concluding the Selma to Montgomery marches. These efforts led to the August 6 signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Listen

The story of Bloody Sunday and today’s pilgrimage to Selma (Voices of the Movement | Washington Post) 25:14

Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March (The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University) 29:41

Watch

John Lewis: The Selma to Montgomery Marches (Time) 5:57

March from Selma to Montgomery (Biography) 4:11

Longer Watches

John Lewis: Good Trouble 1:37:09

Selma 2:08:00

Read

Across That Bridge: A Vision for Change and the Future of America (Book)

Oral History of Charles Bonner and Bettie Mae Fikes during Selma (Civil Rights Movement Veterans)

Marching for Freedom: Walk Together, Children, and Don’t You Grow Weary (Book)

Anniversary of the Voting Rights Act (Rep. John Lewis Press Release)

Voting Rights (Rep. John Lewis)

March (graphic series):

Learn More

Feb 12–Apr 16, 1968: Memphis Sanitation Strike

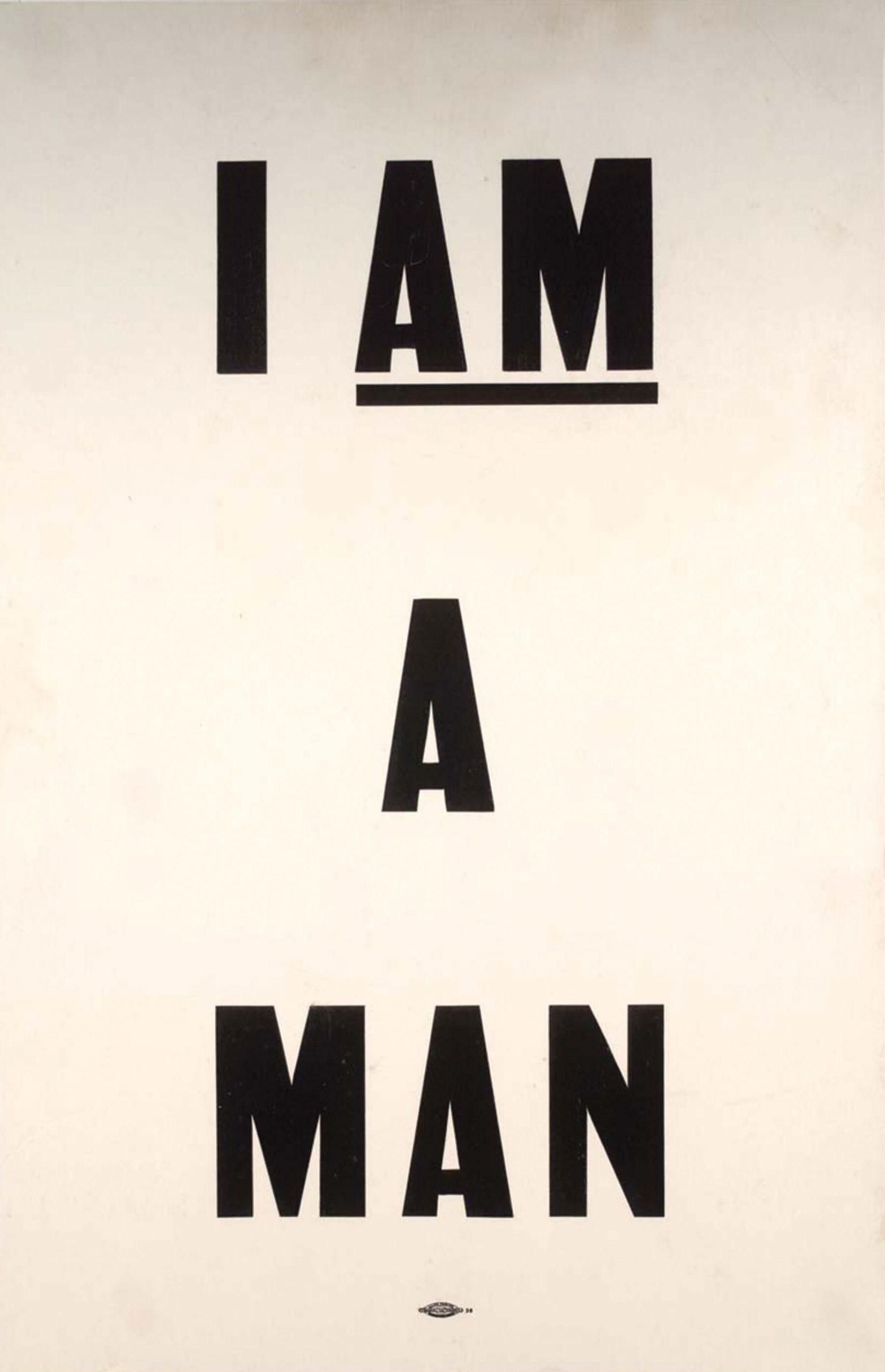

This poster by an unidentified designer became the symbol of the march.

The "I Am A Man" mural was designed by rap artist Marcellous Lovelace in a modern graffiti style and was installed by BLK75. It can be found on S Man St. in Memphis, TN, close to the National Civil Rights Museum. It shows the sanitation workers protest on March 28, 1968, an important event within the Civil Rights Movement, originally captured by photographer Richard L. Copley.

President Barack Obama speaks with surviving participants of the Memphis Sanitation Strike. Photo credit: Lawrence Jackson/Official White House Photo

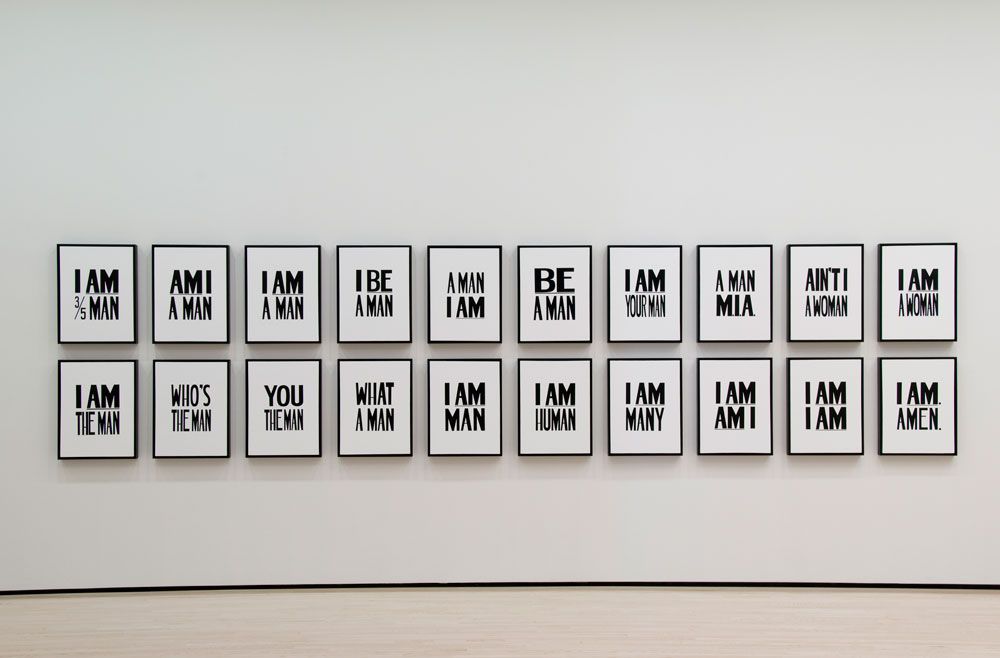

The iconic "I Am A Man" poster continues to inspired, even in the contemporary art world. This series by Hank Willis Thomas connects "I Am A Man" to similar statements like "I Am Am I" and "I Am Many."

Protestors for the Black Lives Matter movement cross the Brooklyn Bridge holding a sign of Colin Kapernick asking, "Do You Understand Yet?"

Since the start of the nationwide shutdown in response to COVID-19, sanitation department strikes have been taking place across the country, from Alabama to Ohio, and most vocally in Louisiana. Sanitation workers, 28% of whom are People of Color, demand and deserve proper personal protective equipment like all other essential workers. Such strikes have historical precedent: just a few decades ago, the widely-known Memphis Sanitation Strike took place, and Black people marched to demand safer conditions for sanitation workers, whose basic human rights were being overlooked. This remains the case today.

After two sanitation workers were crushed to death by a faulty garbage compactor, workers fed up with a lack of safety measures created a labor union to strike for improved working conditions and wage increases. Using non-violent civil disobedience, the protesters found themselves in an increasingly volatile atmosphere. The violence culminated with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., who had been in support of the strike and present at many related gatherings.

The protest continued after his death and gained recognition of the sanitation union, wage increases, and improved conditions.

Listen

I Am A Man: Photographer Richard Copley Recalls His First Assignment, 50 Years After the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike (Tales from the Reuther Library) 18:00

We Came Through (StoryCorps) 14:44

The Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike (Stuff You Missed in History Class) 39:00

Watch

AM I a Man? (Great Big Story) 6:05

1300 Men: The Memphis Strike ’68 (The Root) 6:30

Read

The Brutal Life of a Sanitation Worker (New York Times)

How Women Shaped the Sanitation Workers’ Strike in Memphis, Tennessee (Saving Places)

Learn More

2013–Present Day: Black Lives Matter

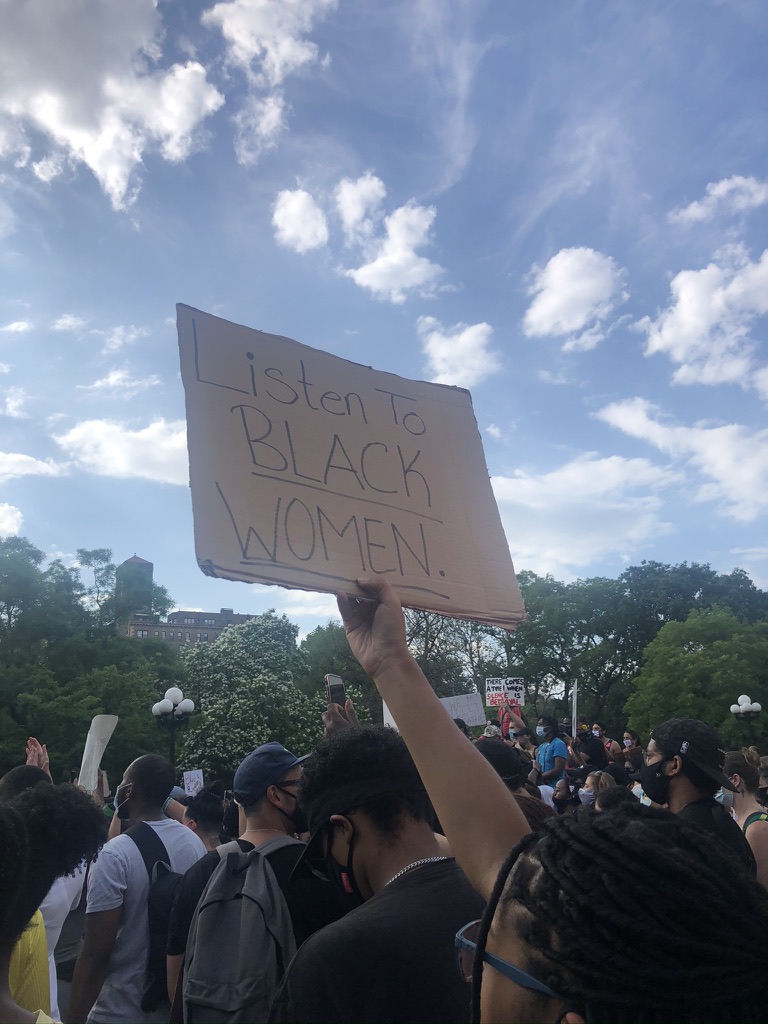

#TheTakeBack; Bronx, NY, June 7, 2020.

Posters for the movements take on different shapes and forms—but the messages carry a similar tone.

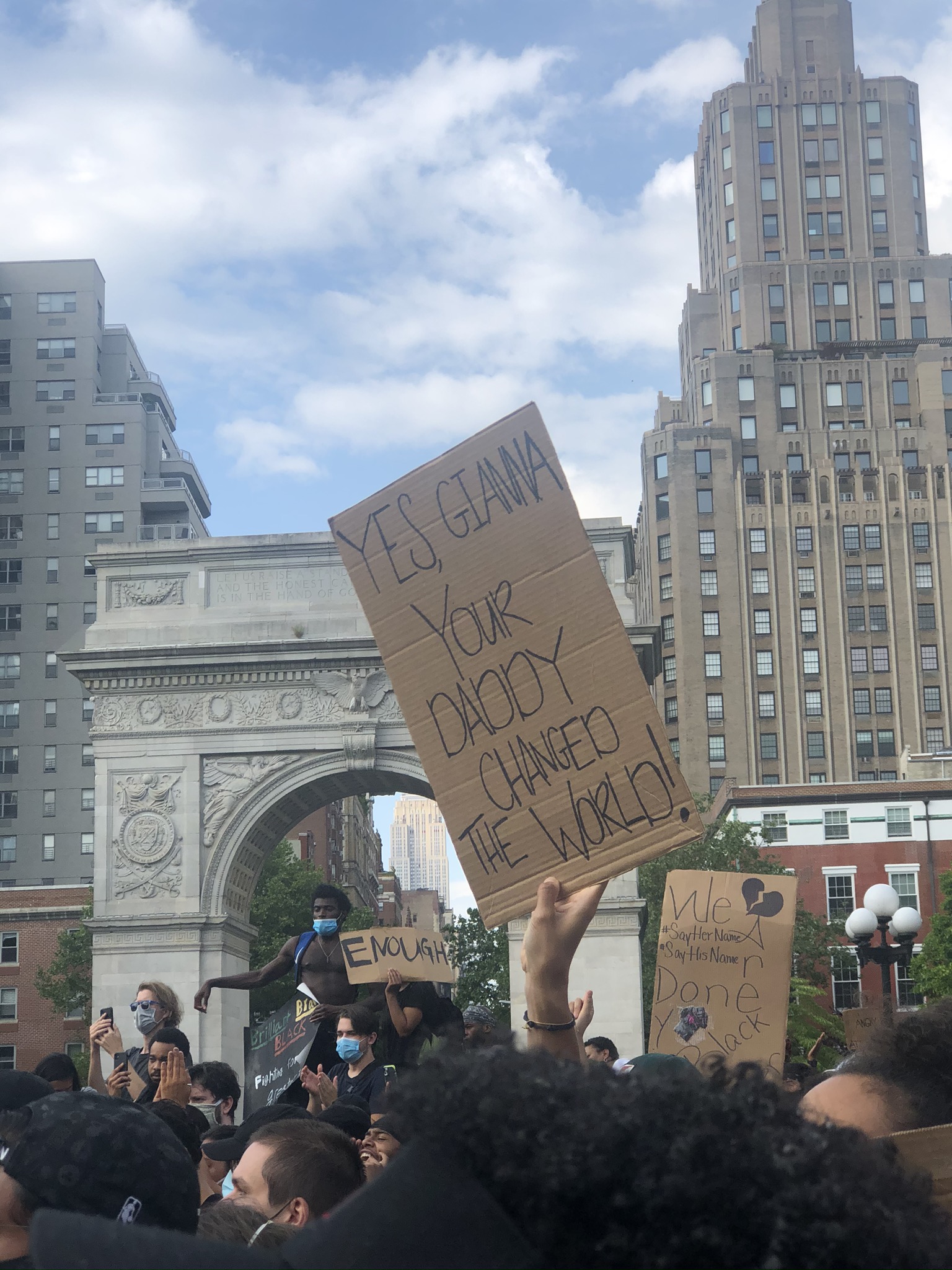

The March for Stolen Lives and Looted Dreams; NYC, June 6, 2020

The March for Stolen Lives and Looted Dreams; NYC, June 6, 2020

The March for Stolen Lives and Looted Dreams; NYC, June 6, 2020

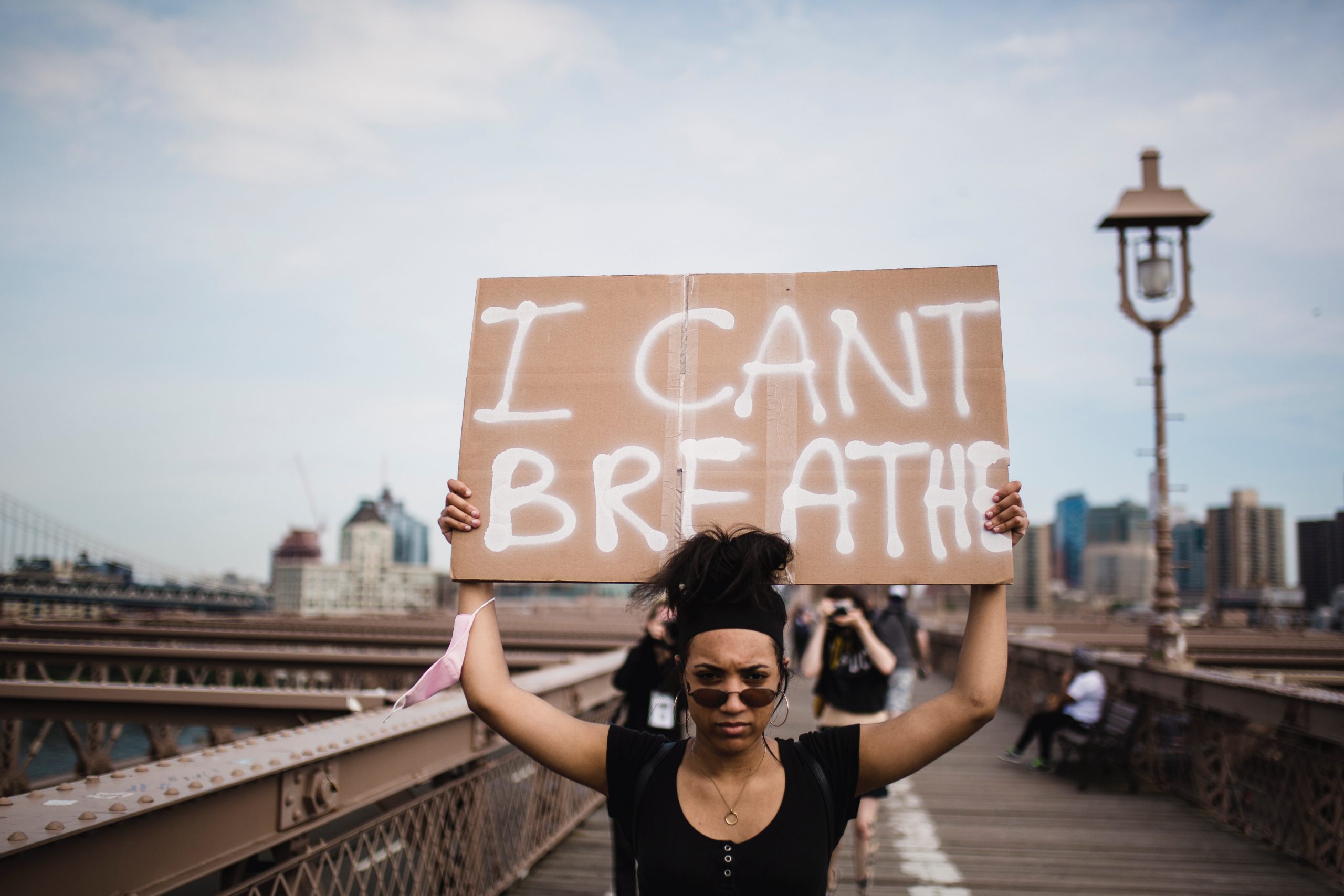

The phrase "I can't breathe" has carried throughout the movement from the murder of Eric Garner to most recently as George Floyd and Elijah McClain.

Black women started Black Lives Matter (the movement) and continue to fight for equity.

#BlackLivesMatter has continued to draw attention to the murders of Black men and women. Recently, the murders of Breonna Taylor—a 26 year old emergency room technician—Ahmaud Arbery—a 25 year old resident of Glynn County, Georgia—and George Floyd sparked nationwide protests calling for the arrest and sentencing of those who killed them.

As with many protests, the posters used in the rallies highlight words that are significant to the activism surrounding police brutality. Within the current protests, approaches to activism that involve dismantling State structures that contribute to violence include a movement to #defundthepolice. Additionally, attention is being called to media censorship, curfew resistance, and accountability of corporations that profit off of Black lives.

Another important aspect of the movement is placing intersectionality at the forefront and understanding the role of Black women, while acknowledging their leadership and voices in these discussions. In order to tackle structural violence, the movement for Black Lives has been one that explicitly recognizes the very foundation of white supremacy and the large role it plays in violence against Black and brown people.

Listen

What Matters (Black Lives Matter)

A Decade of Watching Black People Die (Code Switch) 22:37

Black Lives Matter: Five Years On (The Takeaway) 5:25

Watch

In completing Posters in Protest, a conversation emerged between two of Poster House’s educators around visual media being created for the Black Lives Matter movement. This video is a discussion between Maya Varadaraj and Es-pranza Humphrey as they explore shock value, social media, and “memefication” of the people memorialized in the movement.

An interview with the founders of Black Lives Matter | Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi (TED) 15:57

Read

Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower (Book)

We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom (Book)

Learn More

- Support Black Owned Businesses

- Support Black Owned Restaurants: Eat Okra

- Support Black-run Food Blogs: SoulPhoodie

- Support Black Spaces: Ethel’s Club

- Support Black-run Museum Initiatives: Museum Hue

- Select List of Black Museums:

We hope you’ve found this chapter of Posters in Protest informative and inspirational. Check back soon for more from this series in the future.