Black Power to Black People: An Interview with Curator Es-pranza Humphrey

.Next Month, Poster House will be unveiling a new season of exhibitions, including the much anticipated Black Power to Black People: Branding the Black Panther Party. As a compliment and further analysis of the exhibition, we spoke with curator and museum educator Es-pranza Humphrey to learn more about the upcoming show.

Poster House: Could you tell us a little about your background and how you found your way to Poster House?

Es-pranza Humphrey: I’ve been in the NYC museum world since I was a teenager, when I was selected to be a part of the internship program at the New-York Historical Society (N-YHS). The organization offered me a college internship, and eventually I found my way to the education department, making connections with program facilitators at various New York museums. Though I have my bachelor’s degree in history and a master’s degree in American Studies, I decided to challenge myself by interviewing for an educator position here at Poster House. Since then, I’ve been able to combine my passion for history, teaching, writing, and art as a way to interact with our fascinating collection of posters.

PH: What inspired you to curate this exhibition? Could you talk more about the journey and process of putting this show together?

EH: I was approached by our Chief Curator about this exhibition in the summer of 2020. We had been given access to a catalog of posters, prints, photographs, and newspapers related to Black empowerment from the Merrill C. Berman Collection. I was encouraged to explore narratives based on the material. One of my first ideas was to create a timeline of the idea of “Black Power,” beginning in the 1890s and ending into the 1970s. However, I felt like the collection strongly centered on the history of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and I wanted to investigate this further.

I thought about how the concept of the “Black Power Movement” has manifested itself in different ways throughout history. Ideas like Black nationalism and Black self-sufficiency have always existed, but the language and imagery associated with them have evolved over time. The Black Panther Party seemed to combine the militant image of Black Power with organizing and community activism—and the exploration of these concepts felt like a unique narrative worth exploring within a design-focused museum.

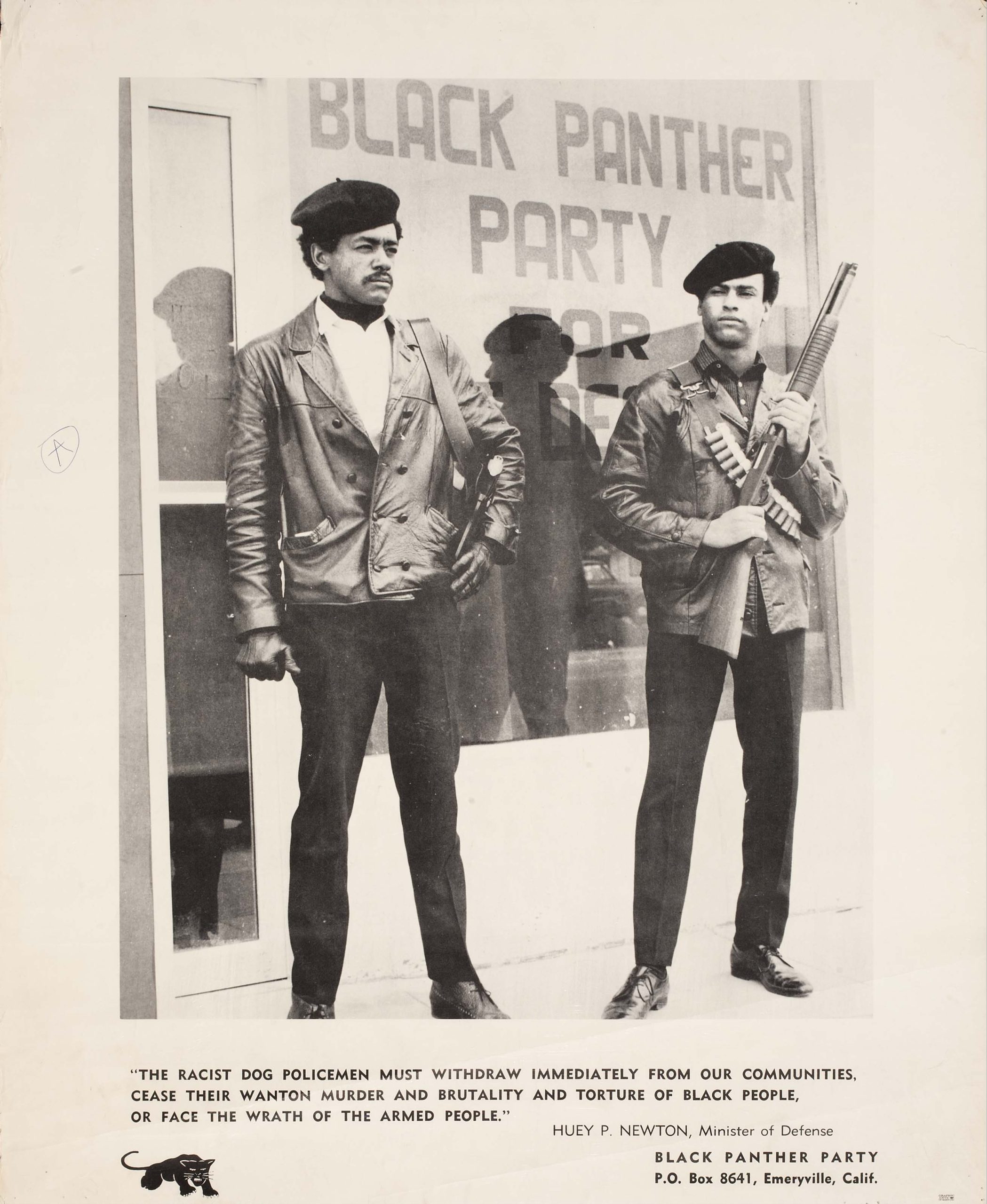

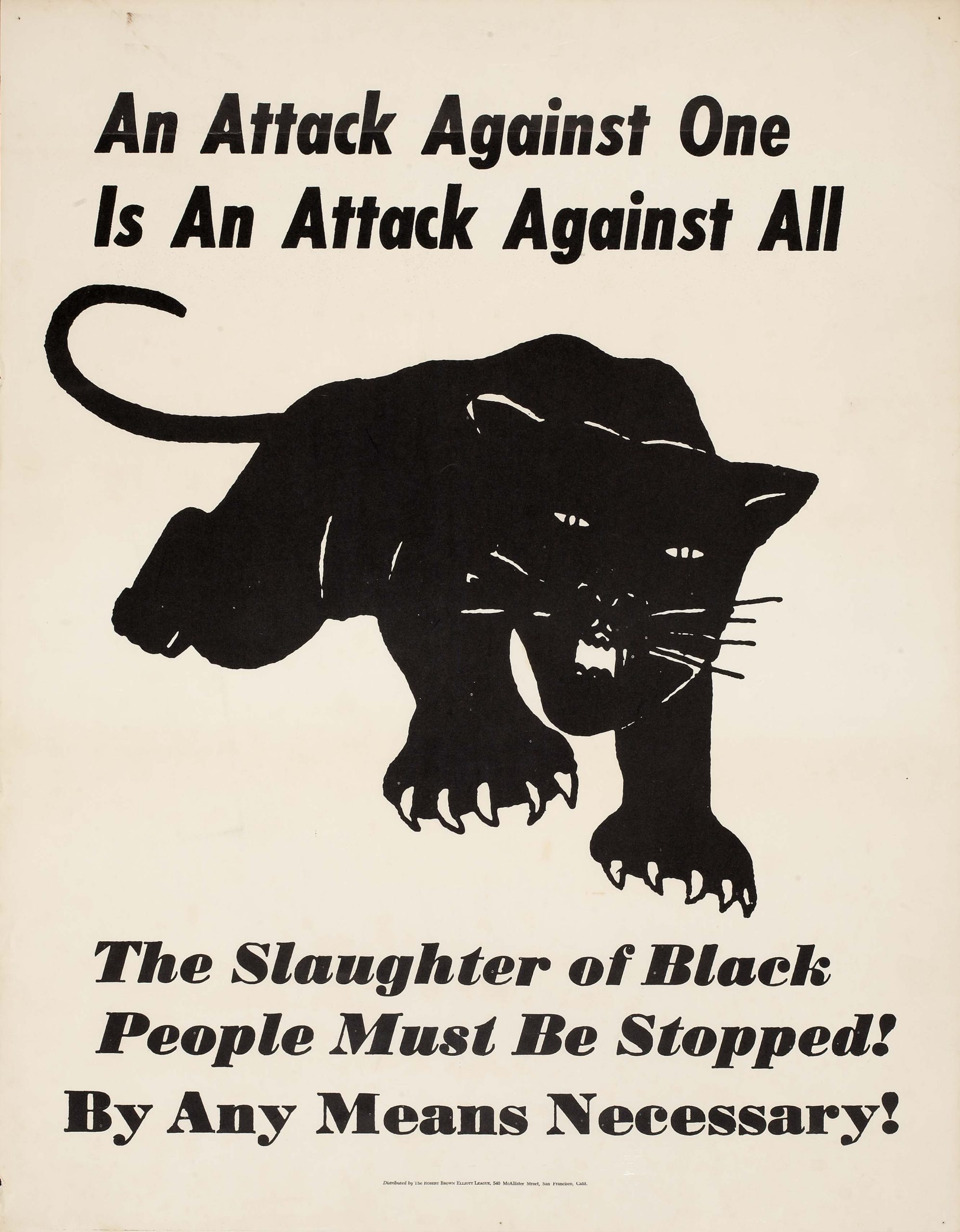

Left Image: Bobby Seale and Huey Newton in Front of Black Panthers Headquarters, Designer Unknown, 1968

Right Image: An Attack Against One is An Attack Against All, Designer Unknown, 1968

Images: The Merrill C. Berman Collection

PH: Why do you believe this exhibition is important? What modern issues facing Black Americans do you believe connect with the ideological goals of the Black Panther Party?

EH: This exhibition is important because there are people living today that were members, leaders, veterans, and supporters of the Black Panther Party. They continue to preserve the legacy of the organization. While we can speak more openly today about issues like police brutality, intersectionality, and pro-Blackness, these conversations are not new—they merely reflect how the contemporary cultural climate is making Black history and Black identity more visible. In terms of visual language, I think modern Black Americans must navigate the outward image of Black Power in more unique and clever ways. Black Power to Black People: Branding the Black Panther Party reminds viewers that we should center Black humanity by way and use of text and image. I believe that the posters and newspapers featured in the exhibit help explain why this idea is important.

PH: What was the role of Black women in the day-to-day operations of the Party? What role did they play in building their graphic design identity?

EH: This question was perhaps the most crucial part of researching the exhibition for me. I continued to ask myself: how can I tell the story of the women of the Party?

Women comprised about sixty percent of the Black Panther Party’s membership and were actively involved in organizing, creating, and leading the organization. These women were also integral in the Free Breakfast Program and the health initiatives of the BPP, and were vital in ensuring that the organization’s essential operations—both public facing and behind the scenes—functioned smoothly. This was especially true in later years when many of the male members were either murdered or incarcerated at the hands of the state. Women, who were often already at the forefront, assumed leadership positions in their absence.

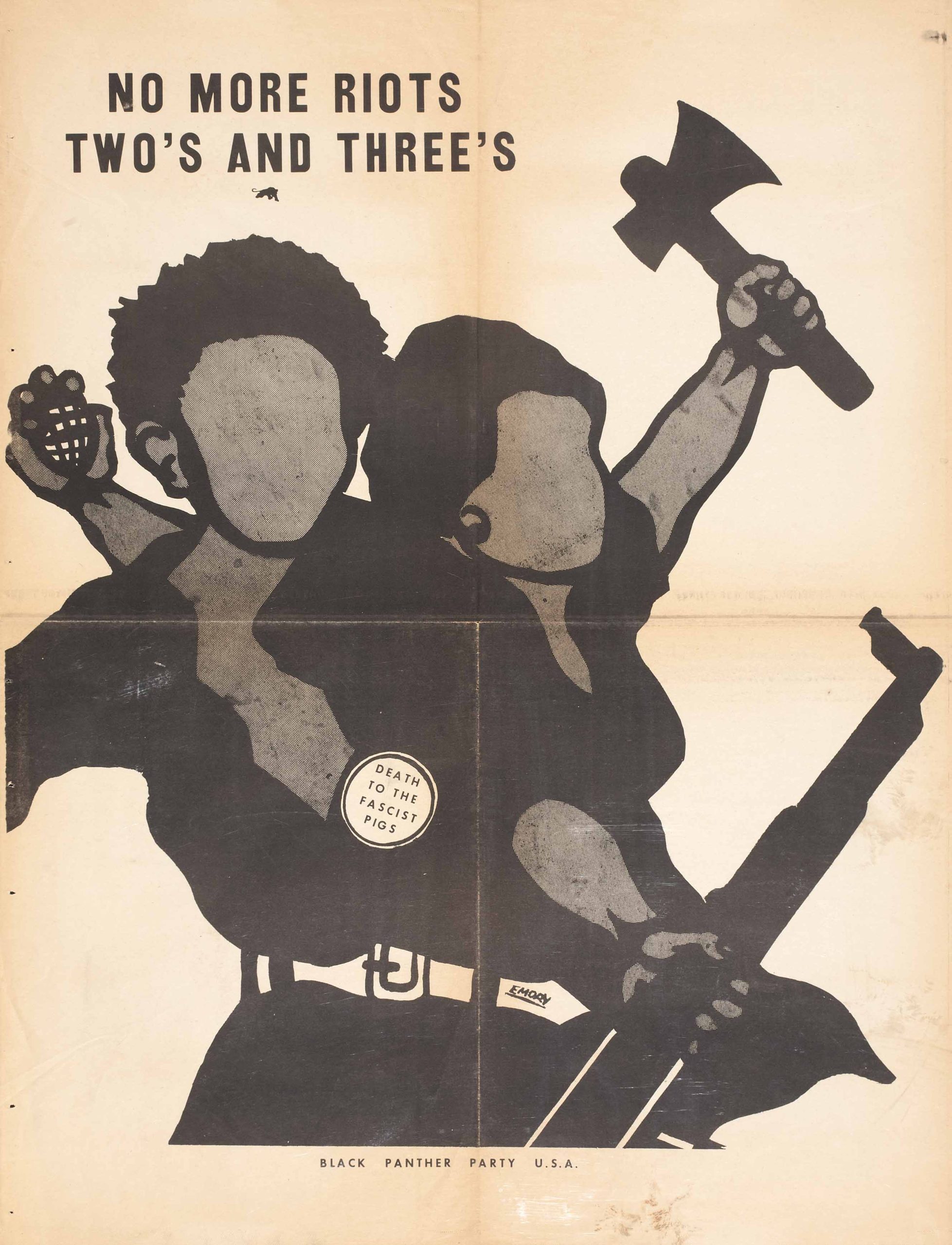

What is most interesting about the graphic design identity of the BPP is the fact that it presents women in dual identities. Part of the function of the branding was to humanize Black people. In humanizing Black women in particular, they presented them as both caregivers and revolutionaries. We see a lot of images of armed women and women standing in formation. We also have imagery of women at the headquarters, amongst children, and selling the party’s in-house operated newspaper. I made sure to specifically spotlight M. Gayle Asali Dickson, one of the early designers of the Black Panther newspaper, as she is often overlooked within this narrative.

No More Riots Two’s and Three’s, Emory Douglas, 1970

Image: The Merrill C. Berman Collection

PH: How has organizing this exhibition changed your view on the Black Panther Party? Did you learn a new aspect of their history that surprised you?

EH: Yes! I always knew that women played a significant role in the Party when it came to organizing, writing, and speaking publicly on behalf of the Black Panthers. In researching for the exhibition and interviewing members, I came to understand how women were integral in physically presenting the image of Black Power and balancing the feminine and masculine ethos of the organization. It’s something that is constantly depicted in photographs. Still, we never really think about the impact of that type of statement for Black women at the time, many of whom are still alive.

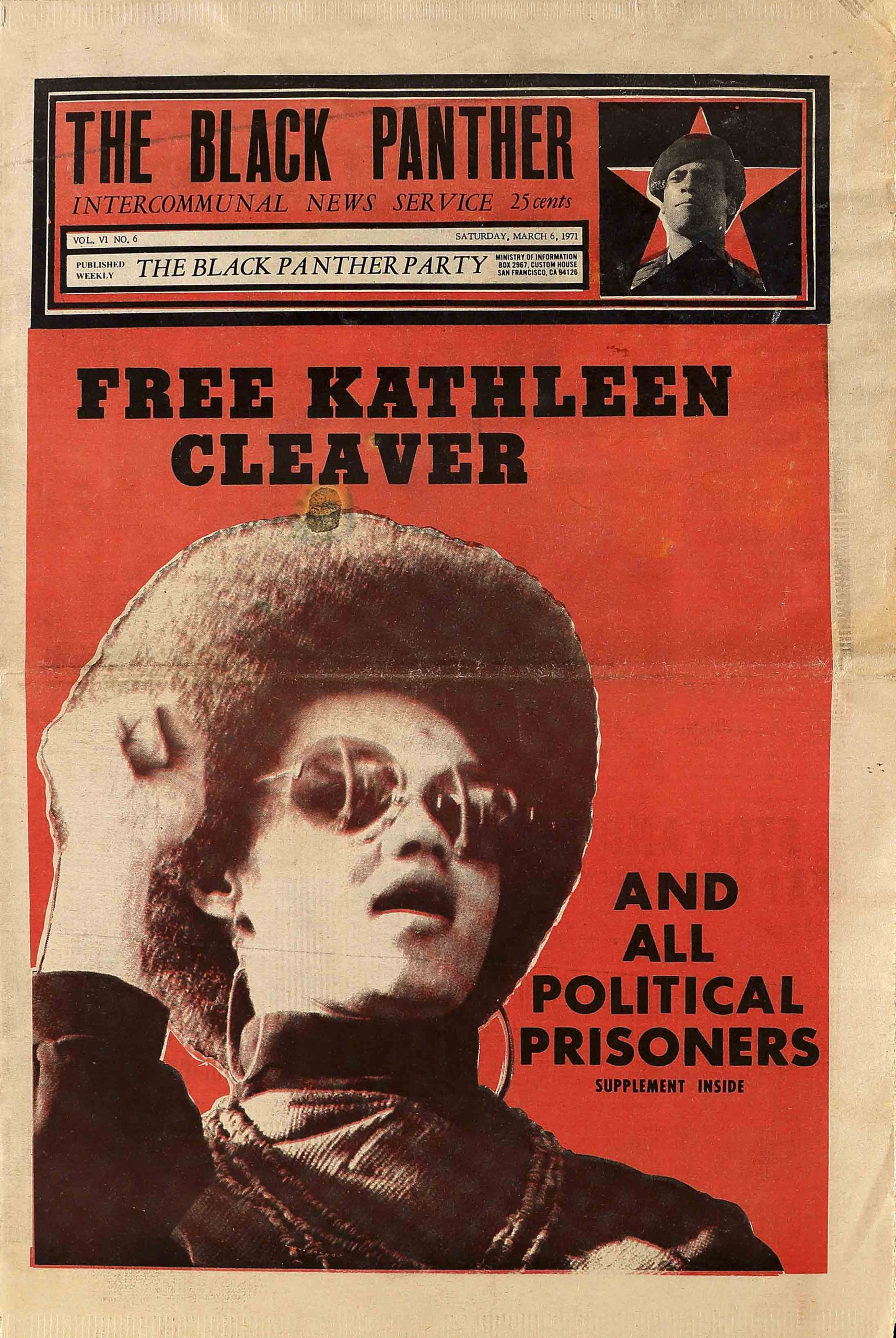

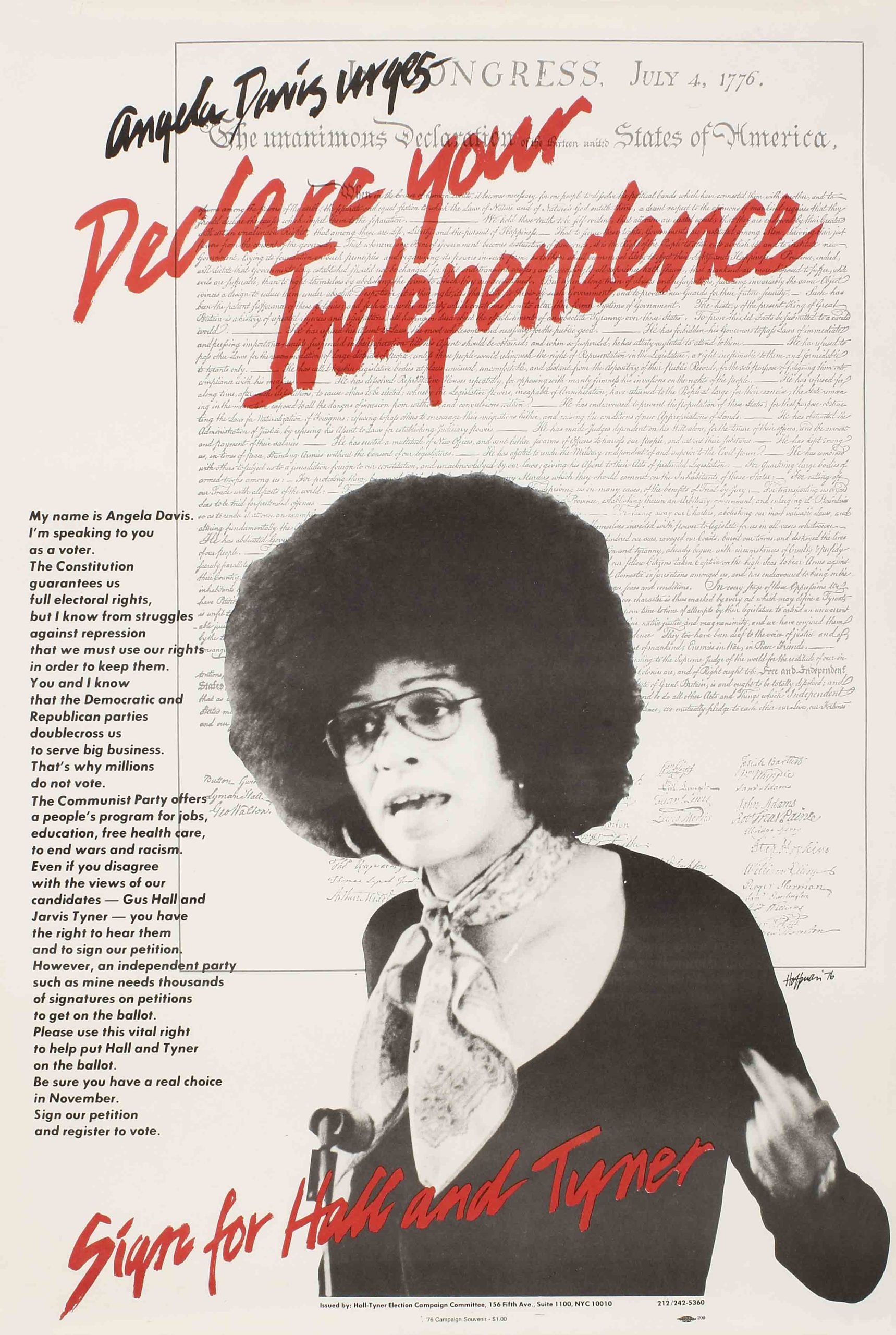

Left Image: The Black Panther, 1971

Right Image: Angela Davis Urges—Declare Your Independence, Designer Unknown, 1976

Images: The Merrill C. Berman Collection

PH: Is there a specific lesson or moral you’re hopeful our visitors will take away from seeing this exhibition?

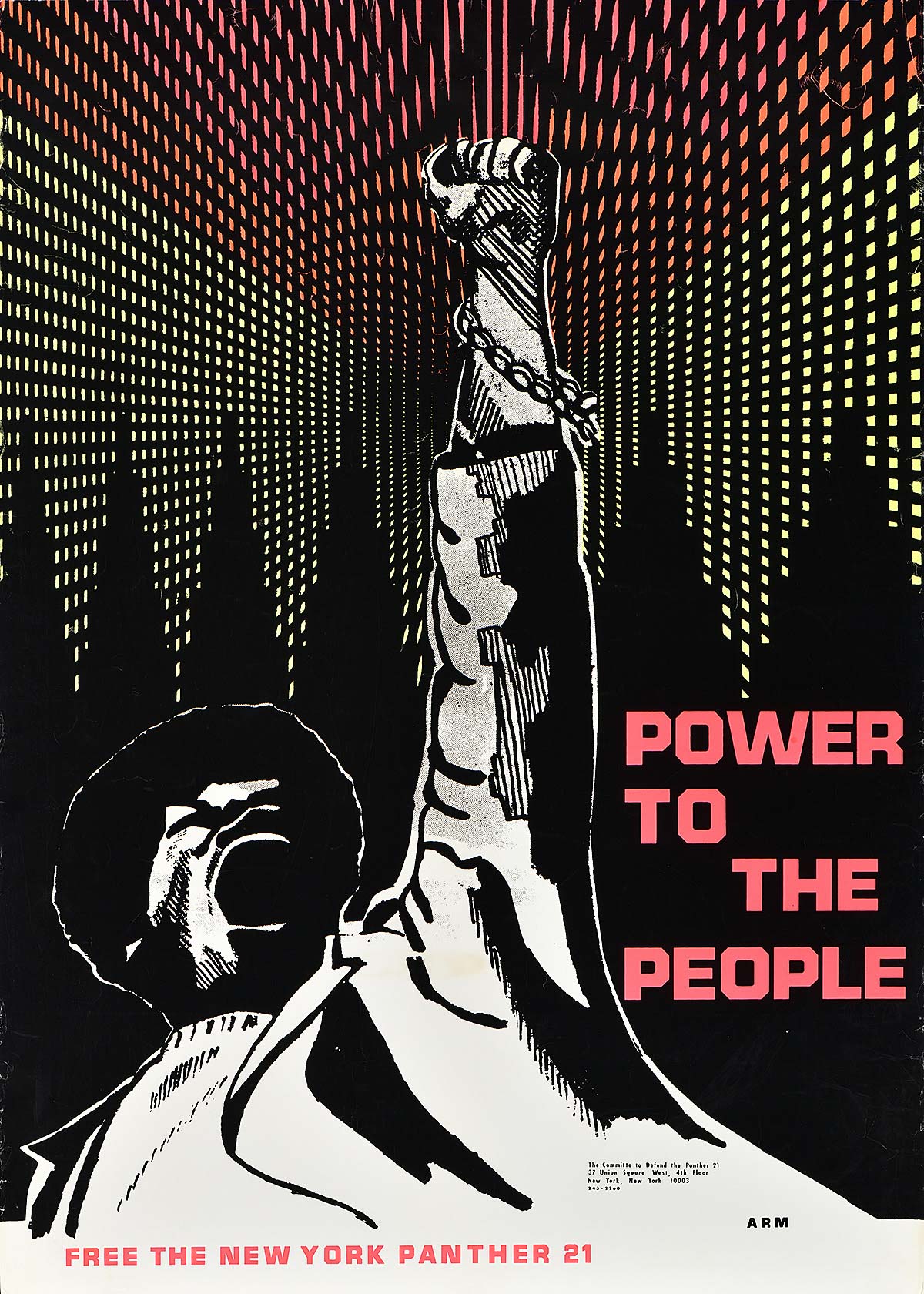

EH: Aside from understanding the impact of posters, prints, and newspapers in creating a visual language that helped brand the Black Panther Party, I want visitors to enjoy the exhibition! Reading, processing, and reflecting on the material took a lot of emotional and intellectual labor. I tried to create an experience that didn’t center on brutal or violent imagery, but imagery that was uplifting of the Black experience. I want the museum’s visitors to appreciate how the Party humanized its members and its leaders. The posters, with bold colors and notable iconography, are meant to grab the public’s attention and invite inquiry.

Power to the People, Designer Unknown, 1969

Image: Poster House Collections

PH: Any final words of advice for future curators of color?

EH: My advice is specifically for Black women. Find your place in the museum world. Finding space in the curatorial department is ideal, but we need more Black women in these institutions in general, advocating for ourselves! Apply to fellowships, apply to internships, apply within the various departments in a museum, and get your foot in the door so that our presence can be known and felt.