Damned Memories

.

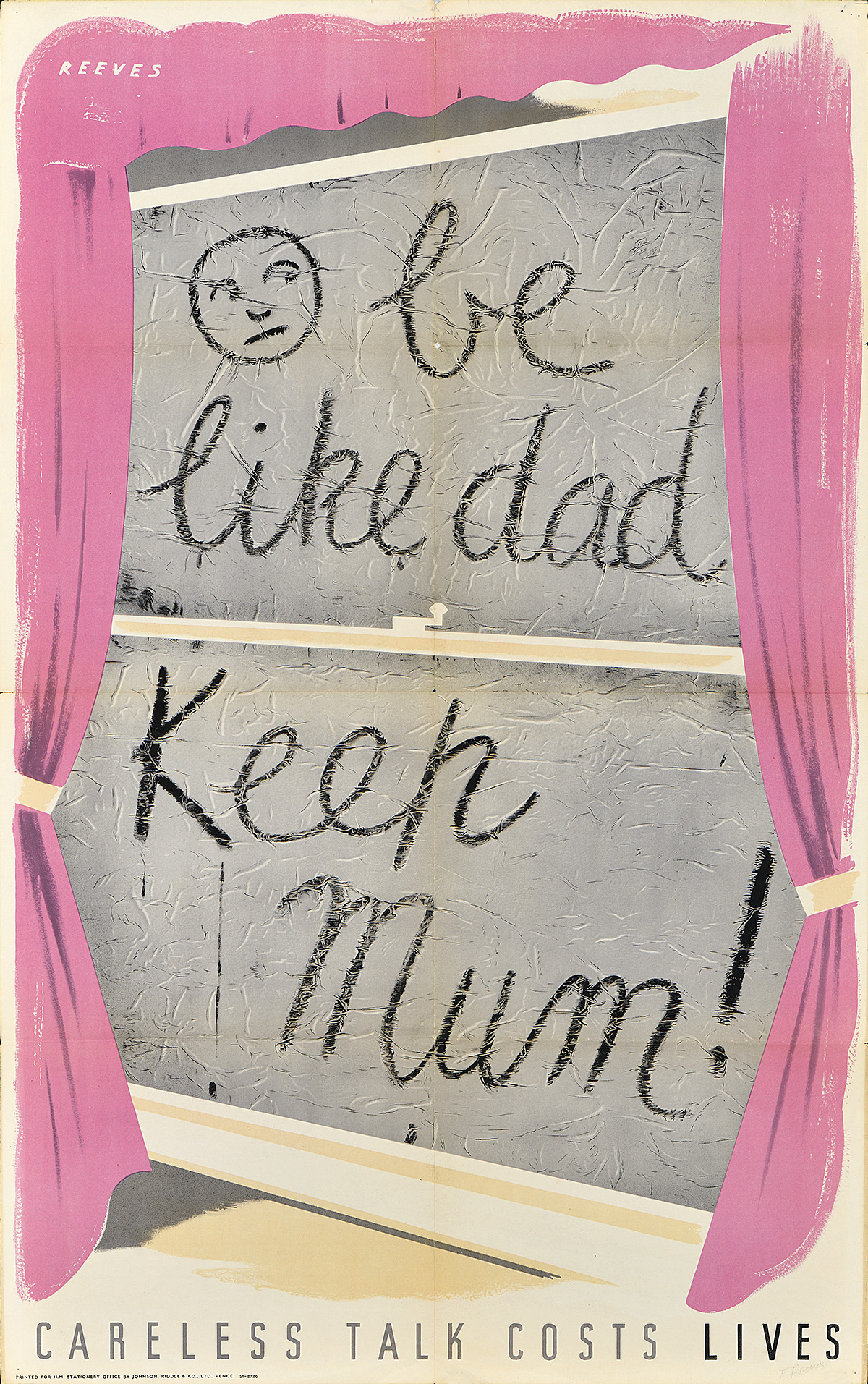

Left: Prima Mostra Nazionale Istruzione Tecnica (First National Exhibition of Technical Instruction), 1937

Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna

Right: Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

The current exhibition, The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy, has come to life in the main gallery of Poster House in New York—but it was born on the roof of a church in Naples.

It’s a marvelous place, just what you’d want if you were looking to fill your vase with a bouquet of poet’s roses: a small apartment with a smaller terrace and a smallest table, set against the edge of the church’s dome. You and an imposing marble bishop holding vigil over the entire city. Naples is a loud place—loud as they come, really—but it’s not difficult to find the charm in it: everything smells like food, and a seemingly eternal procession of marching bands and religious types wander through the neighborhood like beads being threaded onto a string; they stop honking traffic but for the occasional young Italian men on scooters sneaking through on their search for their winsome-yet-anonymous mates, ready to blunder into any number of drums, trumpets, and people carrying saints on their shoulders, in the oft-futile pursuit of their goal.

I came to write the exhibition text on the heels of 12 months of research but far ahead of its due date, mostly because, after a year of being pregnant with Italian fascism, I was eager to get the baby out. I came to Naples also because I like the warm, wet blanket of the Southern Italian winter, and am comforted by the aroma of wood-burning ovens that rises up from the sewer-scents of the streets.

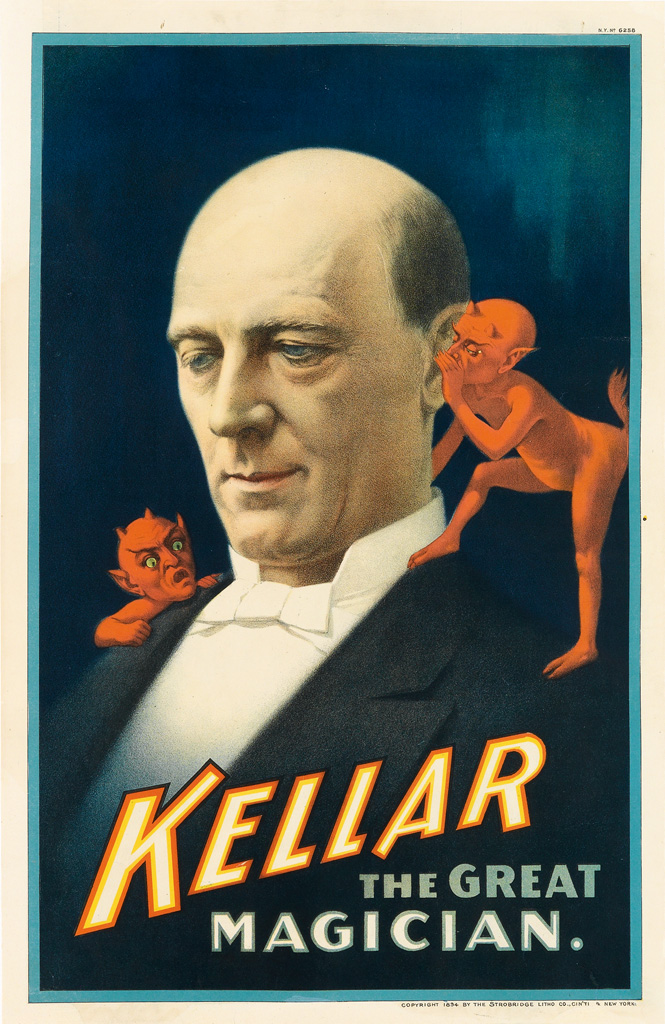

Left: Mostra della Rivoluzione fascista (Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution), 1932

Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna

Right: Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

But also: I wanted to put aside a day not for the museum but for myself. Of little coffees and visiting churches in the service of, or perhaps as an excuse for, meeting up and making up with an old, lost friend: make amens and make amends.

Wandering with her through the places the tourists don’t go, it was easy to remember how softly one can love Italy: the smell of bread, the sight of laundry, towns still standing after so many centuries of damage without repair. Naples is, in a way, the queen of this—cobbled together over three thousand years by a million craftsmen against a filthy bay, her shell is made of salt water and she’s a blinding sight. The city crumbles, shows the wounds where the light enters, the thorns that reduce us to roses, hundreds of churches wounded in so many terrible ways, their roofs broken, their bulkheads ruined by earthquakes, volcanoes, American bombs—souvenirs of every shock, every storm that’s knocked them and rained marble and rocks down on the faithful. History here is lived and ignored in equal measure.

Ending up in Rione Sanità—once the toughest neighborhood of hard-living Naples but now its well-muraled TikTok destination—we walked out of one such church and right smack into something I wasn’t expecting:

A note from Benito Mussolini.

In the industrial eigengrau of this inner-city slum, on a grimy plaque covered in 80 years of both car exhaust and cigarette exhaust from the locals, he’d left an announcement: Italy, he wanted the nation’s poorest city’s poorest citizens to know, was now an empire. In a fake, all-caps ancient Roman font, he declared:

THE ITALIAN PEOPLE

HAVE CREATED EMPIRE WITH THEIR BLOOD

THEY WILL FERTILIZE IT WITH THEIR WORK

AND THEY WILL DEFEND IT AGAINST

ANYONE WITH THEIR ARMS

IN THIS SVPREME CERTAINTY LEGIONNAIRES RAISE HIGH

THEIR ENSIGNS, THEIR IRON, AND THEIR HEARTS TO SALVTE

AFTER FIFTEEN CENTURIES THE REAPPEARANCE OF THE EMPIRE

Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

It’s rare to meet Mussolini in Italy. Outside of the small village of Predappio, where a souvenir shop and marble bust mark the spot where Il Duce will be dead forever, there is almost no clear trace that the man existed. His name isn’t on the buildings and there are no pictures of him or even tacky items in souvenir stands. Considering that the peninsula’s other famous tyrant, Julius Caesar, is still commemorated in statues from desk-size to the positively imperial and numbering well into the thousands, the damnatio memoriae (damned memory) of Mussolini, the nation’s sawdust caesar, is really remarkable.

The ancient Romans perfected the idea of damnatio memoriae as a sort of ultimate punishment, exceeding even torture and execution. By removing the names of The State’s hated individuals from inscriptions and documents, and even engaging in large-scale rewritings of history, they could scrub not just the person but the entire memory of that person from the popular imagination. With nobody to remember you, did you even exist?

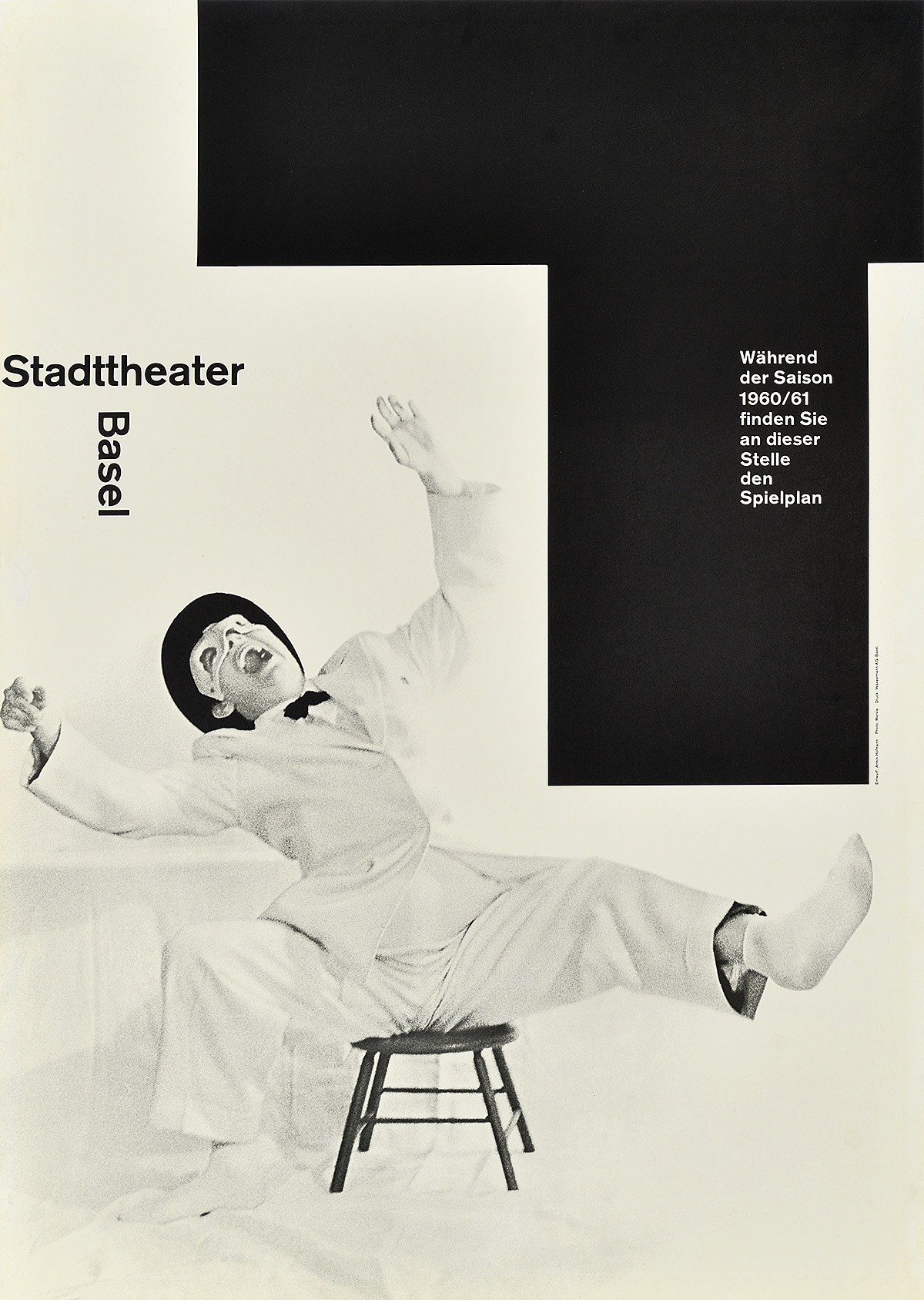

Left: 1o Circuito Città di Portogruaro (First Circuit of the City of Portogruaro), 1933, by Luciano Vignaduzzo

Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna

Right: Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

Mussolini, in the period of Allied occupation after the war and the founding of the Republic, has undergone a very distinct case of damned memory: other than some trivia (a granddaughter in parliament, books in train-station shops if you’re looking for them) you might not know that he’d ever existed, that during the ventennio—the roughly 20-year period of his rule—he’d changed Italy so completely and, in many ways, built the foundation of today’s nation. There are no monuments, no statues, certainly no holiday for the man who’s most remembered, when he’s remembered at all, for his brutality.

And yet, he’s also everywhere. In The Future Was Then we show, again and again, how pervasive the regime was in the art form that most frequently faced the Italian people: advertising. “Fascism should more properly be called corporatism,” Mussolini said, “because it is the merger of state and corporate power.” And so, over the course of his rule, Italy moved out of the art nouveau movement that had charmed its culture in the years leading into World War I and into a conformist art deco style that would take it through the war to follow: Italy, the nation, became through its advertising not just a government but also a style, a message, a typeface.

Left: Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

Right: Vincere come il Duce comanda (Win as the Leader Commands), 1941, by Ettore Mazzini

Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna

Strolling around any big Italian city—or, for that matter, any number of small Italian towns—even the laziest of informed observers will note that they’re actually, well, walking with Benito. The explosion of Italy’s bureaucracy occurred during the fascism regime; it is still rare to find a government office that doesn’t have, in war-size print, a typeface to let you know exactly which unnamed dictator had it built. Sports fields? Absolutely. Hospitals? You bet.

These objects of impertinent permanence remain, perhaps, the longest legacy of a regime whose achievements were otherwise short-lived: a small African land grab was the acme of their evolution but the immediate declaration of empire on the side of a wall is still there, eight decades later, to punctuate she, and I, walking to lunch.

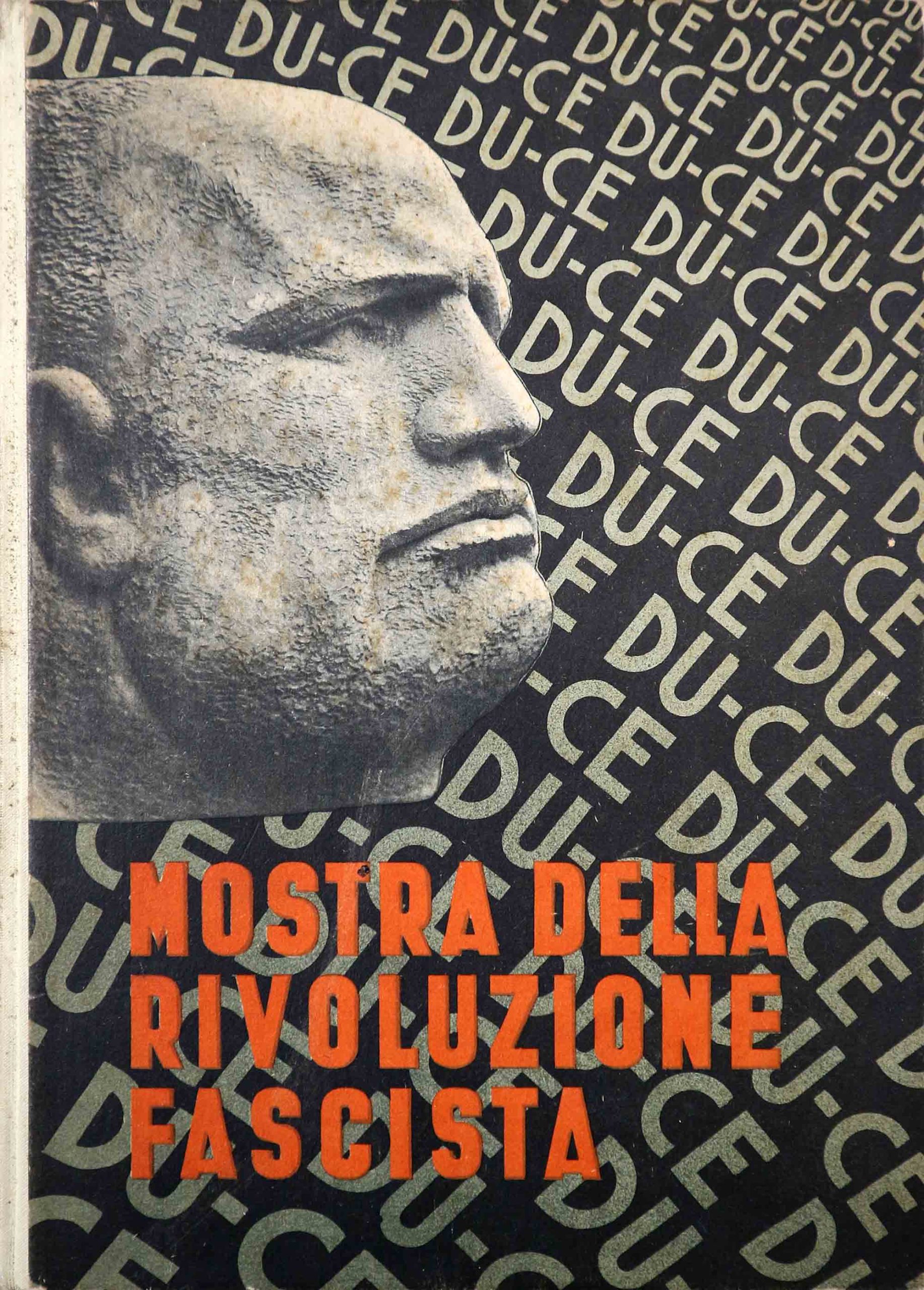

Left: Mostra della Rivoluzione fascista (Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution), 1932

Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna

Right: Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

It’s a phenomenon you see elsewhere, of course, even in the stormy American present to which allusions in our exhibition will understandably be assumed: fascism is as ancient as time, and as modern as tomorrow.

And so, If you go to get your driver’s license in Italy, you enter the office under the lettering of the man who once seized power here in a march on Rome. Walking into a coffee bar, you order a cappuccino under the typeface favored by the same man later murdered by his own citizens. When you board a train, your departure board is almost certainly announced with a font directed by Il Duce himself; when you get off the locomotive, your arrival is announced in fascist typeface, among the last remnants of a dictator whose only surviving portrait statue is the one over his grave.

Left: Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

Right: Crociera aerea del Decenniale (Decennial Air Cruise), 1933, by Luigi Martinati

Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna

I’ve got a degree in linguistics, which is to say that I’m in love with language. Italian has what are to the anglophone ear some unusual verb cases: most notably the remote past, which is something that happened a long time ago and can never happen again. If you’re into genealogy (as I am), you see it used a lot to refer to the dead who once lived but are no longer: fu. So on Italian documents I’m Brenno, fu Sarah—Brenno, son of Sarah. She lived. And yet Italian grammar has a remote past but not a remote future. You can account for every step from Caesar until now, but your tomorrows are always numbered.

Sometimes that past finds you in a textbook; every once in a while, it’ll turn up in a museum exhibition. And, maybe, it might even turn up on a plaque in a bad neighborhood while you’re on your way to lunch.

Perhaps those old tyrannies remain the masters of our past: no matter how they turn us upside down, or we them, they still leave us plenty, and plenty, of letters.

Left and Below: Photograph by B.A. Van Sise

Right: Campeggio, 1936, by Mario Borrione

Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli Collection, Bologna