George Hoellering, an unsung pioneer of cinema

.George Hoellering’s name is inextricably linked with the illustrious history of London’s Academy Cinema on Oxford Street, the preeminent British art house cinema in the decades after World War II, and with that of Peter Strausfeld, his tireless collaborator who designed the cinema’s posters. But Hoellering’s role as theater manager and promoter of this vibrant international cinema has overshadowed his own artistic output both in the years before he fled to Britain from Hungary in 1936 and after his release from an internment camp on the Isle of Man in 1941. Yet Hoellering should also be remembered as one of the pioneers of docu-fiction cinema; his film Hortobágy (1936) reflected the influence of American explorer Robert Flaherty, often considered the father of documentary film, while his poetic aesthetic and social vision anticipated the postwar neorealism of Italian filmmakers like Roberto Rossellini.

T.S. Eliot and George Hoellering, c. 1950

Source: The Eliot-Hale Letters

George Hoellering (born Georg Michael Höllering, July 20 1897, Baden near Vienna–February 10 1980, Suffolk, England) was born into a highly cultured milieu; his father, Georg Höllering, was a musician and theater manager in Vienna. The younger Hoellering was exposed early to the performing arts. His film career began in earnest in 1919, when he became the licensee of the Schikaneder Kino in Vienna—one of the city’s most influential cinemas. From 1919 to 1924, he managed the venue and started building practical experience in exhibition and operations. In the early 1920s, amidst the dynamic cultural ferment of Weimar Germany, Hoellering moved to Berlin. There, while still overseeing his Vienna cinema remotely, he worked in various capacities— as an editor of film shorts, as a director of experimental films, and as an assistant production manager.

His role as production manager on Kuhle Wampe (Who Owns the World?, 1932), directed by Slatan Dudow from a script by Bertolt Brecht, proved to be a critical point in Hoellering’s career. The film, an unvarnished depiction of working-class hardship during the Depression, was deeply controversial and was initially banned by the German government. Hoellering’s involvement in this left-leaning film foreshadowed his later commitment to socially engaged cinema. In 1932, with the rise of the Nazi party, Hoellering—whose wife was Jewish—decided to leave Germany. After a brief period in Vienna, he and his family moved to Hungary in early 1934 along with their cinematographer friend László Schäffer.

Hortobágy, 1936

Source: Czechoslovakian Film Database

There, they quickly embarked on the making of Hortobágy (1936), a film that would define Hoellering’s early creative identity. He had just discovered the existence of the csikós, a tribe of horse-mounted herdsmen on the Hungarian plains who had established a unique way of life for more than a thousand years. Yet nobody had ever had the idea of filming them before and the herdsmen had never actually seen a camera. (Hoellering had to convince them to trust him by riding untrained horses in front of them.) Hortobágy is a hybrid documentary; shot entirely on location with amateur actors, villagers, and local herdsmen, it has a naturalistic style much like that of Robert Flaherty’s ethnographic films (Hoellering was especially fond of Flaherty’s first film, Nanook of the North from 1922, depicting the lives of Inuits). Hortobágy combines documentary imagery with a loosely structured story about life, tradition, and generational change in this rural society and is based on the short story “Darksome Horse” by Hungarian writer Zsigmond Móricz, who came to meet the herdsmen during the filming. The production was arduous. Hoellering struggled for two years to get financial backing. His friendship with László Passuth, who became his bank manager, ultimately allowed him to take advantage of Hungary’s restricted currency system and the government’s financial incentives encouraging foreign entrepreneurs to pour money into the local economy. Once it was finished, the movie faced new difficulties when the official censors demanded cuts. In spite of these challenges, the theatrical release of Hortobágy was extraordinarily well received by the press. Sándor Márai, the great Hungarian novelist and playwright best known for his 1942 novel Embers, wrote in his newspaper review of the film: “Weekdays and holidays, life and death, traditions and despair, dignity and prudence, helplessness and supercilious wisdom, misery and fate radiate upon us from every image.” In 1936, in the face of growing instability in Central Europe, Hoellering emigrated to England, carrying with him Hortobágy as both personal accomplishment and professional calling card. The film was screened in London in December 1936 at the New Gallery Cinema by The Film Society. Writer and journalist Graham Greene praised it in The Spectator as “one of the most satisfying films I have seen: it belongs to the order of Dovzhenko’s Earth without the taint of propaganda. The photography is extraordinarily beautiful, the cutting superb.” Elsie Cohen, the owner of the Academy Cinema, also loved Hoellering’s movie and had heard about his past activities as movie-theater manager in Vienna; she hired him as codirector and later managing director of her cinema.

Left: Film Still from Tim Marches Back, 1944

Source: Imperial War Museum

Right: Still from Skeleton in the Cupboard, 1943

Source: Imperial War Museum

With the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Hoellering—an Austrian national in Britain—was classified as an enemy alien and, in 1940, was interned on the Isle of Man by the authorities. During his internment in the Ochan Camp, he directed and organized an amateur musical production, What a Life!, with music by a fellow internee, the Austrian composer Hans Gál. After his release by the end of 1941, Hoellering immediately contributed to the British war effort through cinema; he created his own production company, Film Traders, and produced and directed many short films, newsreels, and informational pieces for the Ministry of Information. Some of these shorts also incorporated animated sequences at a time when animated film production was virtually nonexistent in Great Britain. In his shorts Peak Load Electricity (1943), Salvage Saves Shipping (1943), Skeleton in the Cupboard (1943), and Tim Marches Back (1944), the animation was created by Peter Strausfeld, who had been his fellow inmate in the camp. Hoellering was an innovator in the field of film animation along with a few other pioneers like the Hungarian John Halas and his partner Joy Batchelor, and, a few years later, Larkins Studio, which employed the German-born Peter Sachs.

Film Stills from Shapes and Forms, 1950

Source: British BFI Bluray

In 1950, Hoellering returned to film production and direction with the short-length film Shapes and Forms. This experimental work was created as a sort of extension to a 1949 exhibition organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London named 40,000 Years of Modern Art. The idea was to question the revolutionary claims of modern art by confronting artworks by such famous modern artists as Brancusi, Chagall, de Chirico, Picasso, and Matisse with prehistoric African and Asian tribal artifacts. Intentionally conceived without either commentary or subtitles this unique, deeply hypnotic film blurs the lines between ancient and modern; the images are accompanied only by the music of Hungarian composer László Lajtha, one of the favorite students of the celebrated composer and pianist Béla Bartók, who also composed for Hortobágy. Interestingly, Shapes and Forms precedes by three years Chris Marker’s and Alain Resnais’s Les statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die, 1953), with which it shares a lot of formal similarities: black-and-white close-ups and tribal statues moving to contemporary music. The French film similarly suggests that Europeans have borrowed a lot from early African and Asian art; however, it also explores the impact of colonialism and cultural appropriation on African art and heritage.

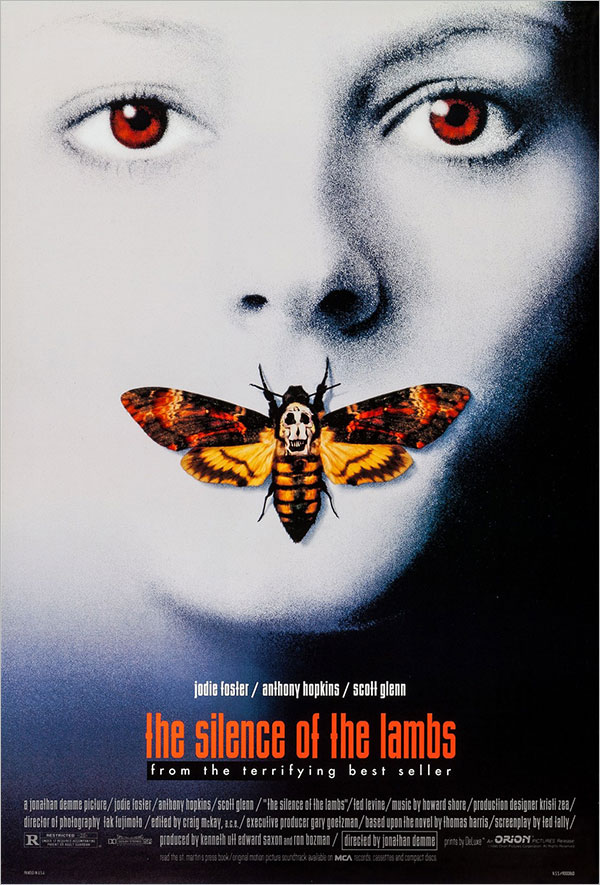

Murder in the Cathedral, 1935

Poster House Permanent Collection

During his internment, Hoellering received a copy of T. S. Eliot’s verse play Murder in the Cathedral (1935). The play, an exploration of the assassination of Thomas Becket, then Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170 following his confrontation with King Henry II, made a profound impression on Hoellering, and he resolved to adapt it to film at the earliest opportunity. He and Eliot met soon after the war—the writer was initially hesitant about the translation of his play to the screen but eventually agreed, encouraged by Hoellering’s knowledge of the work and after watching Hortobágy in a private screening. Hoellering deliberately used both stage actors and amateurs in this production as he had done in Hortobágy, further inspired by Italian neorealism and the emotionally austere films of the great Danish film director Carl Theodor Dreyer, works like The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and Day of Wrath (1943). Hoellering chose Father John Groser, an actual member of the clergy known as the “Rebel Priest of the East End,” to play Becket; Groser consistently spoke out against injustice and inequity from the pulpit. He had a reputation for decrying the rapacious behaviour of landlords and, in 1939, led a peaceful strike to pressure slum landlords to cease the unlawful evictions of tenants—a success. The choice of this particular clergyman to play the film’s central character introduced a powerful veracity and a moral intensity to the production as well as a sober, unspectacular incarnation of “this troublesome priest.” The film, which premiered at the 12th Venice Film Festival in 1951, is the result of Hoellering’s radical experiments, most notably his decision to preserve the original verse form of the text and to film the play in the claustrophobic confines of a church rather than in the real Canterbury Cathedral, deemed too much changed since 1170 to be a suitable location. The music was once again entrusted to László Lajtha; this was the third time Hoellering worked with him. Hoellering also asked T. S. Eliot to record his reading of the whole play so that it might serve as a guide to the rhythms of the verse and used Eliot’s voice for the words of the Fourth Tempter. As a film director, Hoellering eschewed the often florid style of conventional historical epics in favor of the contemplative austerity of Dreyer. The film was honored at the Venice Film Festival when Peter Strausfeld (credited as Peter Pendrey) won the award for Best Production Design; the challenging, like-minded French director Robert Bresson won several awards, including the International Award for Diary of a Country Priest, while Japanese director Akira Kurosawa won the Golden Lion (the top prize) for Rashomon.

Father John Groser as Thomas Becket in Murder in the Cathedral, 1951

Source: DVDBeaver

It should now be clear that George Hoellering was not just the manager of the Academy Cinema. He was also one of the pioneers of docu-fiction, a precursor of neorealism, a stylistically demanding filmmaker whose work can be related to that of Carl Theodor Dreyer and Robert Bresson, a creator of avant-garde films in the manner of Alain Resnais and Chris Marker, and, through his production company Film Traders, a founding father of British animation. He was also admired by major writers like Sándor Márai and Graham Greene, and collaborated with Bertolt Brecht and T.S. Eliot. That seems like quite a lot for a man who has long lingered in the shadows and who has only just begun to attract the attention of film historians.