Grind These Heels in Our Wheels: Some World War Two Posters from the Museum’s Collection

.I’ve been cataloguing a great number of American World War II propaganda posters recently, thanks to the museum’s excellent Collections Specialist, Alex Stern, who chooses lists of objects for me to work on each month. She’s obviously highly intuitive, for she surely knows nothing of my childhood devotion to ancient war and gangster films (the Hollywood movie, shown on Thursday at 9pm on BBC2 for years, was typically the high point of a dismal London school week bedeviled by mirthless teachers, team sports under drizzle, and the conjugation of Latin verbs). Anyway, I thought I’d show you a few examples here, several featuring my favorite, extremely dated, tough-guy slogans.

Let’s Give Him Enough and On Time (1942) by Norman Rockwell

Private Collection

Norman Rockwell’s Let’s Give Him Enough and On Time from 1942 appears in curator Angelina Lippert’s recent exhibition at Poster House, Lester Beall & A New American Identity. As Angelina points out, after the Office of War Information (OWI) was set up in June 1942 to define and communicate the federal government’s wartime propaganda aims, the symbolism and abstraction explored by Beall and very few other American graphic designers were quickly abandoned in favor of posters in the traditional, illustrational style that remains so closely associated with Rockwell (the anti-Beall).

The Madison Avenue advertising men counseling the government assured the OWI that their surveys established irrefutably that the American public preferred the realistic, emotionally stirring conventions of commercial illustration over what it saw as the intentionally obscure artifices of foreign modernism. Rockwell’s composition was part of a deluge of production-incentive posters issued by federal agencies, urging factory workers to keep up the supply of ammunition and weapons for soldiers in the front lines. The famous illustrator stated in an interview that he had based the details of this design on a gun crew and a machine gun that were actually sent to his studio by the military after it had approved his original sketch. Rockwell explained that “The gunner insisted that I picture his gun in gleaming good order, but he let me rip his shirt…This final poster represents one of our grand soldiers in a tough spot on the firing line. The coil of cartridge tape and the empty cartridges show that he is about down to his last shot.”

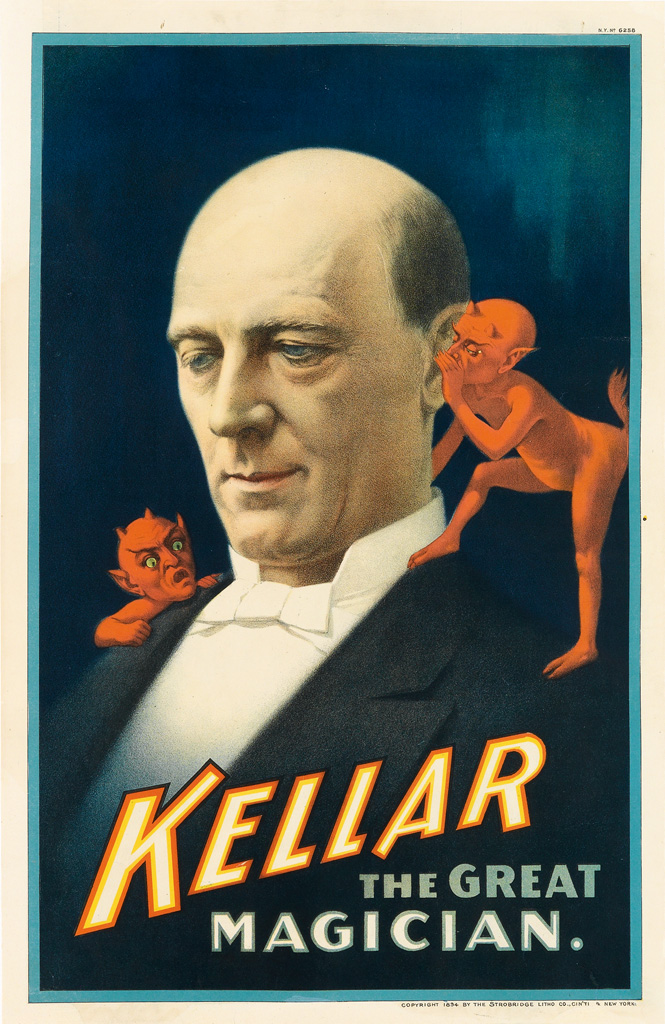

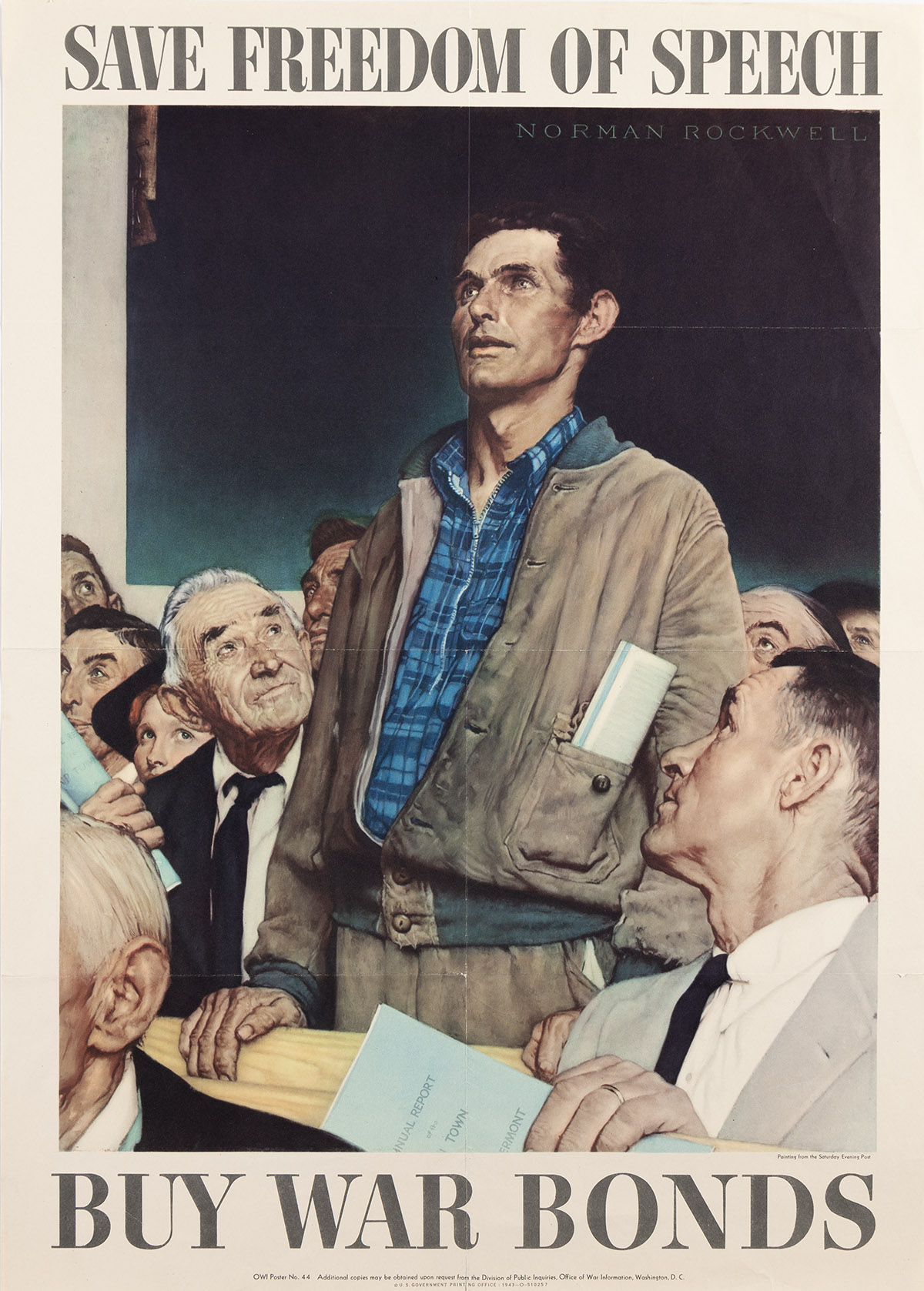

The Four Freedoms (1942), by Norman Rockwell

Images courtesy of Swann Auction Galleries

It is worth noting that Rockwell’s four paintings interpreting the Four Freedoms addressed by President Roosevelt in his annual congressional address on January 6, 1941, ultimately became some of the most familiar images of the era. They were published in consecutive issues of the Saturday Evening Post in 1943 and shown in a traveling exhibition arranged by the Treasury, which also reproduced them as fundraising posters.

Given ‘Em More Firepower (1943) by Dean Cornwell

Poster House Permanent Collection

This 1943 poster by Dean Cornwell (“the Dean of illustrators”), They’ve Got the Guts/Give ‘Em More Firepower was issued by the government’s Ordnance Department and also encourages munitions workers to keep up production (a variant of this composition features the similarly gangsterish tagline “They’ve got the GUTS/Back ‘Em Up with More Metal”). The realistic, melodramatic scene of an American soldier firing a rifle in the foreground while another lands a parachute beside him looks like those in a lot of the illustrated posters promoting Hollywood war movies of the time. This approach made perfect sense: the average American civilian’s mental images of the action in the European and Pacific theaters of war were shaped in large part by the visual idioms of these very films and their promotional materials (some designed by the same illustrators).

Like Rockwell, John Falter, McLelland Barclay (see below), and many of the other artists hired to create propaganda posters, Cornwell had been a successful commercial illustrator before the war, creating advertisements for businesses like Palmolive Soap, General Motors, and Coca-Cola as well as for popular magazines like LIFE, Harper’s Bazaar, and Good Housekeeping. It is reasonable to lament the loss of the aesthetically ambitious compositions that might have been issued by federal agencies during the war if those in the OWI who favored “war art” by well-known artists over the work of commercial illustrators had prevailed over the ad men; but it is undeniable that these illustrators were extraordinarily well positioned to adapt official propaganda to the mainstream tastes, prejudices, concerns, and ideals of the American public—treacly and predictable though some of them now appear.

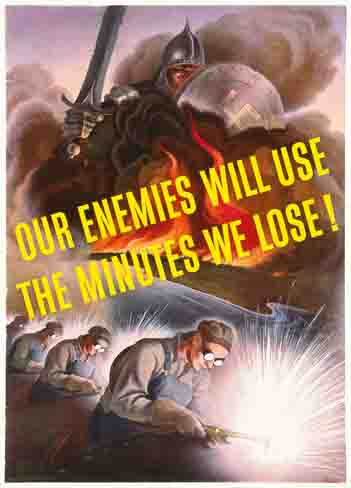

Left: Our Enemies Will Use the Minutes we Lose!

Right: United

Both Poster House Permanent Collection

While wartime production-incentive posters not only promoted increased production of munitions in American factories but also alerted workers to the dire consequences of wasting time and materials (Our Enemies Will Use the Minutes We Lose) or reminded them that their role in the war effort was as critical as that of the fighting men (United/All America is on the March!), Grind these Heels in our Wheels of American Production deployed comic-book style (and gallows humor) to boost workers’ morale.

It was produced by an unknown designer working for the Work Projects Administration (WPA), an agency established in 1935 as the Works Progress Administration under President Roosevelt’s New Deal program to employ millions of Americans in public works projects during the Great Depression. In it, the terrified leaders of the Axis powers—Hirohito of Japan, Hitler of Germany, and Mussolini of Italy, are about to be crushed under the heel of Uncle Sam and ground like mincemeat in the wheels of a vast American-made machine. The message of the poster, which might almost have been designed for the entertainment of a cheerfully loathsome child, could hardly be clearer.

Grind these Heels in our Wheels of American Production

Poster House Permanent Collection

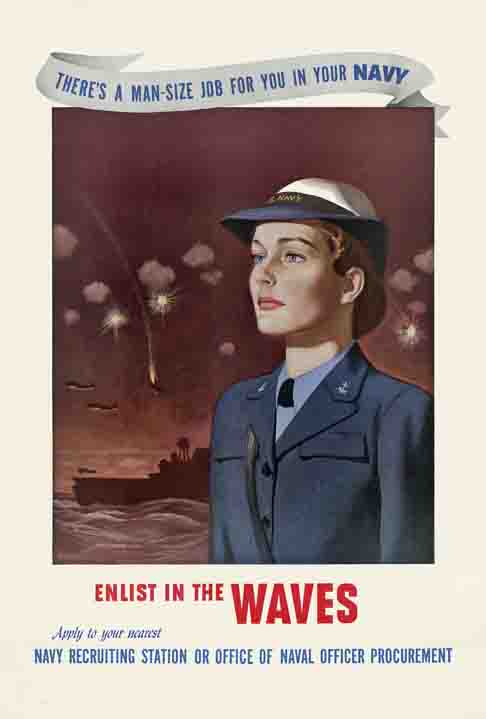

United States Navy Reserve Artist John Falter, who designed more than three hundred posters for the navy, illustrated this 1943 poster, There’s a Man-Size Job for You in Your Navy: Enlist in the Waves, with an image of a woman in uniform apparently unperturbed by the air and sea battles raging behind her. This sort of stalwart female figure with a determined expression, the very antithesis of the wartime pin-up girl or the dangerous siren, appears often in women’s enlistment posters.

By the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it was abundantly evident that women of this kind would be needed to assist in the war effort. On May 15, 1942, Congress created the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) and on July 30, 1942, it established Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), otherwise known as the Women’s Naval Reserve, intended to “expedite the war effort by releasing officers and men for duty at sea and their replacement by women in the shore establishment of the Navy, and for other purposes.” The redoubtable Dr. Virginia Gildersleeve of Barnard College in New York was the head of the Advisory Council for the WAVES; she later observed that “if the Navy could possibly have used dogs or ducks or monkeys, certain of the older admirals would probably have greatly preferred them to women.”

Enlist in the WAVES (1943) by John Falter

Poster House Permanent Collection

Another significant category of wartime posters reflects the government’s efforts to reduce infections from the venereal diseases, especially syphilis and gonorrhea, that had been the greatest cause of preventable medical disability among the troops during World War I. In 1936, in the face of another world war, Thomas Parran was appointed Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service. He launched a new public campaign against venereal disease, one that involved short educational films, school-education programs, and books as well as posters and brochures that counseled both caution and testing and the strict avoidance of “good- time girls.” This campaign was stepped up significantly after the United States entered the war, but the medical evidence suggested that the bold, somewhat abstract health-warning posters initially commissioned by the OWI simply confused the young recruits.

Here again, commercial illustrators were soon hired to devise clearer warnings like this one to be pinned on the walls of military bases and training facilities. This poster, Both of These Men Had Syphilis, probably from 1944, is from a series persuading servicemen to get treatment for the disease, each with a direct written and visual message: in every poster, a man who has received his shots to treat syphilis is shown fully recovered and leading a happy personal life; the other man, who has not sought treatment, is seen alone and hobbling on crutches. The treatment offered is presumably penicillin, the only effective cure. It became widely available to the military in late 1943 but it was not until 1944 that U.S. scientists managed to mass-produce 2.3 million doses of it in preparation for the D-Day landings in June of that year to treat Allied casualties of combat and infection.

Both of These Men Had Syphilis (c. 1944)

Poster House Permanent Collection

This poster, Save Your Cans/Help Pass the Ammunition, urging American civilians to save cans to support the war effort, was part of the government’s Salvage for Victory campaign, launched on January 10, 1942, just a month after Pearl Harbor. It was issued by the Salvage Division of the War Production Board, responsible for ensuring the collection of household materials that could then be sent to factories for reconfiguring as military weapons and supplies. Like many wartime posters, it suggests a direct connection between the efforts of people on the home front and those of the men fighting abroad.

McCelland Barclay’s composition here is certainly more ambitious than most; in it, a woman’s manicured hand feeds empty cans of tomatoes, apparently extending beyond the frame of the image, into the ammunition magazine of a machine gun operated by American soldiers in a desert trench. Barclay was another commercial illustrator who had a well-established career before the war, not only producing work for Collier’s, Redbook, LIFE, and The Ladies’ Home Journal but also for several movie magazines. In 1930, too, Barclay’s Fisher Body Girl was selected by General Motors for a series of advertisements, and she soon became as familiar as the Gibson Girl and the Christy Girl. (This kind of work also served him well during the war, when he became one of the first artists to depict pin-up girl Betty Grable.)

Save Your Cans (1942) by McCelland Barclay

Poster House Permanent Collection

Speaking of canned tomatoes (not Betty Grable): if you should encounter a harmless-looking woman muttering to herself in a Cagneyesque staccato in the canned-vegetable aisle at Fairway (“Give ‘em both barrels!” and “Next Stop Tokyo!”), do not be alarmed. It means that it’s probably time for me to divert my attention for a while to posters for baby food and kitchen appliances. But I’ll be back on the World War II stuff soon, Alex. I’ve got the guts—give me more firepower!