Ludwig Hohlwein’s Poster for the Isidor Bach Clothing Store

.In 1912, Ludwig Hohlwein (1874–1949) designed an advertising poster for Isidor Bach, a high-end Munich store selling men’s Sport und Reisekleidung (sportswear and travel clothing). It shows a group of affluent-looking figures dressed in traditional Bavarian outfits (lederhosen and loden jackets as well as socks and hats ornamented with single feathers are much in evidence) complete with rucksacks, sturdy shoes, and a baleful dachshund. The travelers have just disembarked from a steam train and are readying themselves for a hike in the mountains, visible at the upper right of the composition. It’s a sophisticated but innocuous image, one presumably intended to encourage the viewer to drift inexorably in the direction of the Bach store on Sendlinger Strasse in pursuit of the rich fabrics and leisurely lifestyle so elegantly evoked here. The poster was produced during the period of Hohlwein’s emergence as one of the most innovative German poster designers of his time, and one who regularly promoted the businesses and products of all sorts of Jewish manufacturers, among many other clients.

Hermann Scherrer (1907), Ludwig Hohlwein

Hohlwein trained as an architect in Munich but by 1906 had begun a new career as a graphic designer. His early work was influenced partly by that of the British designers known as The Beggarstaffs (James Pryde and William Nicholson) whose novel, artistic posters were defined by simplified forms, bold silhouettes, and a limited palette of flat colors. He went on to work in the somewhat similar Sachplakat (object poster) style established by his compatriot Lucian Bernhard, in which simple forms and distinctive lettering were integrated into designs that focused chiefly on the object being advertised. Significantly, however, Hohlwein’s version of it incorporated more texture and pattern than the iterations of Bernhard and his other followers. His figures were also more naturalistic and defined by more volume, making them better suited to the promotion of clothing, and partly reflecting the fact that they were often based on posed subjects in photographs. Hohlwein’s reputation in the field was secured in 1908 by his design for a line for the Swiss PKZ fashion house (“Confection Kehl”), one that typically hired the best new artists to produce its advertising, and his work was soon much in demand with firms specializing in men’s tailoring and sporting clothes. In addition to PKZ and Isidor Bach, he also made designs for Hermann Scherrer and Johann Zahne in Munich and for Hermann Hoffmann in Berlin. Hohlwein also created other posters for the distinguished (Jewish-owned) lithographic printing firm of Kunstanstalt Graphia in Munich that published the Bach poster. (Unlike in France, Britain, and the United States, it was not until the 1920s that the large advertising agencies offering design services were established in Germany; German advertising before then was mostly arranged by the manufacturers themselves who commissioned posters from printers like Kunstanstalt Graphia which, in turn, hired designers.)

Wilhelm Mozer (1909), Ludwig Hohlwein

By 1925, Hohlwein had produced some three thousand advertising posters not only for men’s tailoring but also for cigarettes, typewriters, cameras, binoculars, shoes, cocoa, pianos, chocolate, cars and motorbikes, wine, caviar, and countless other products, as well as for sporting events, festivals, entertainments, and tourism for firms all over Europe. In the same year as the Isidor Bach poster, Holhwein also designed a distinctive series of posters promoting the new Munich Zoo, and during World War 1, he was commissioned by the government to design posters mainly for relief funds and war bonds.

Hohlwein’s vibrant and clever 1909 composition for another ritzy Munich purveyor, the Wilhelm Mozer delicatessen and wine dealer, is also in the museum’s collection and well explains his swift progress in his new field. The lobster, so huge that it appears to extend beyond the image into the text space of the design, and the champagne bottles, indicate that Mozer’s was a very sumptuous operation indeed. It was one that also sold “Kolonialwaren” (exotic items from the colonies) but mysteriously claimed, nonetheless, to offer “Alle Lebensmittel zu billigsten Tagespreisen” (all foodstuffs at the cheapest prices every day) as if it were a basic grocery store.

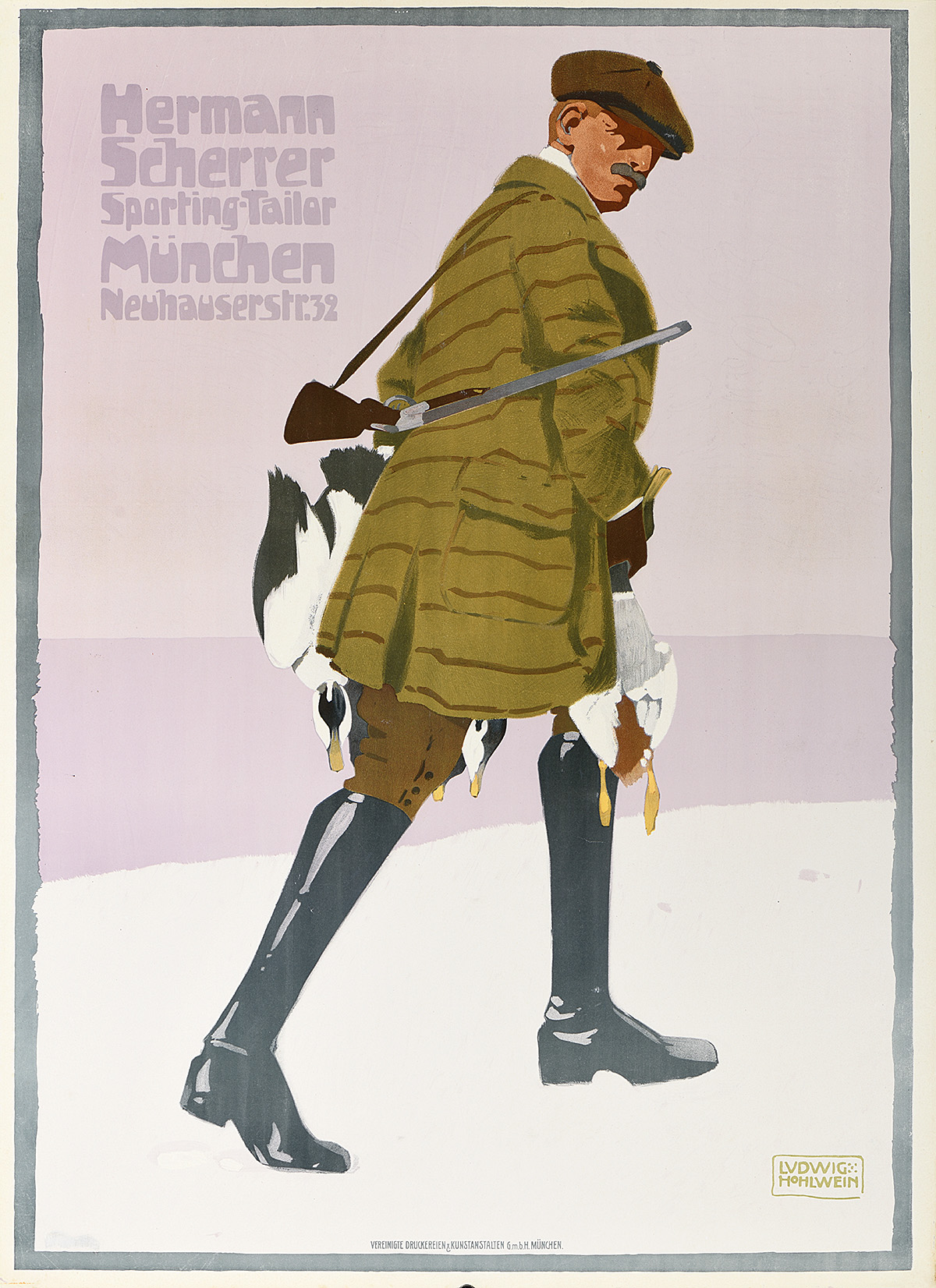

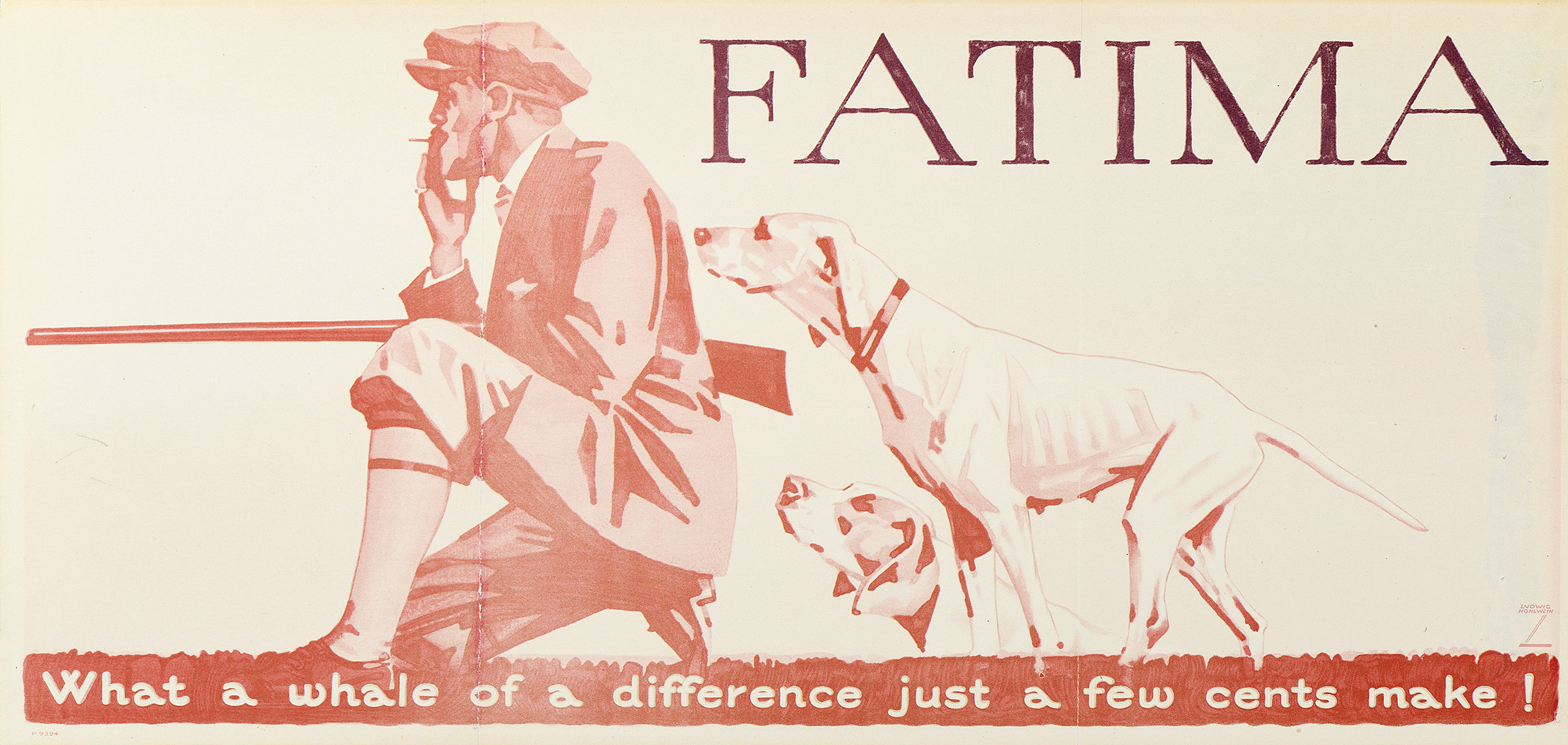

Fatima (c. 1909), Ludwig Hohlwein

During the 1920s, Hohlwein worked in the United States, designing posters for such items as Fatima cigarettes, Granger tobacco, and ultimately for the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. But considerable local competition and the onset of the Depression meant that he never achieved anything like the professional status he had in his home country; Hohlwein therefore returned to Germany in good time to participate enthusiastically in the Nazi racket. He produced far too many propaganda posters for the regime (among them a series of rather sinister images for the infamous Winter Olympics of 1936), as is well known. While it does not diminish his critical importance in the history of 20th-century poster design, this ugly (and lengthy) interlude necessarily stained his moral and international reputation.

Granger (c. 1909), Ludwig Hohlwein

Like all works of art, Hohlwein’s Isidor Bach advertising poster is inescapably embedded in the society and culture from which it emerged. This obviously made it an efficient message carrier—but it also led me to further investigate what I could only assume would become a painful divergence of interest and experience between designer and client.

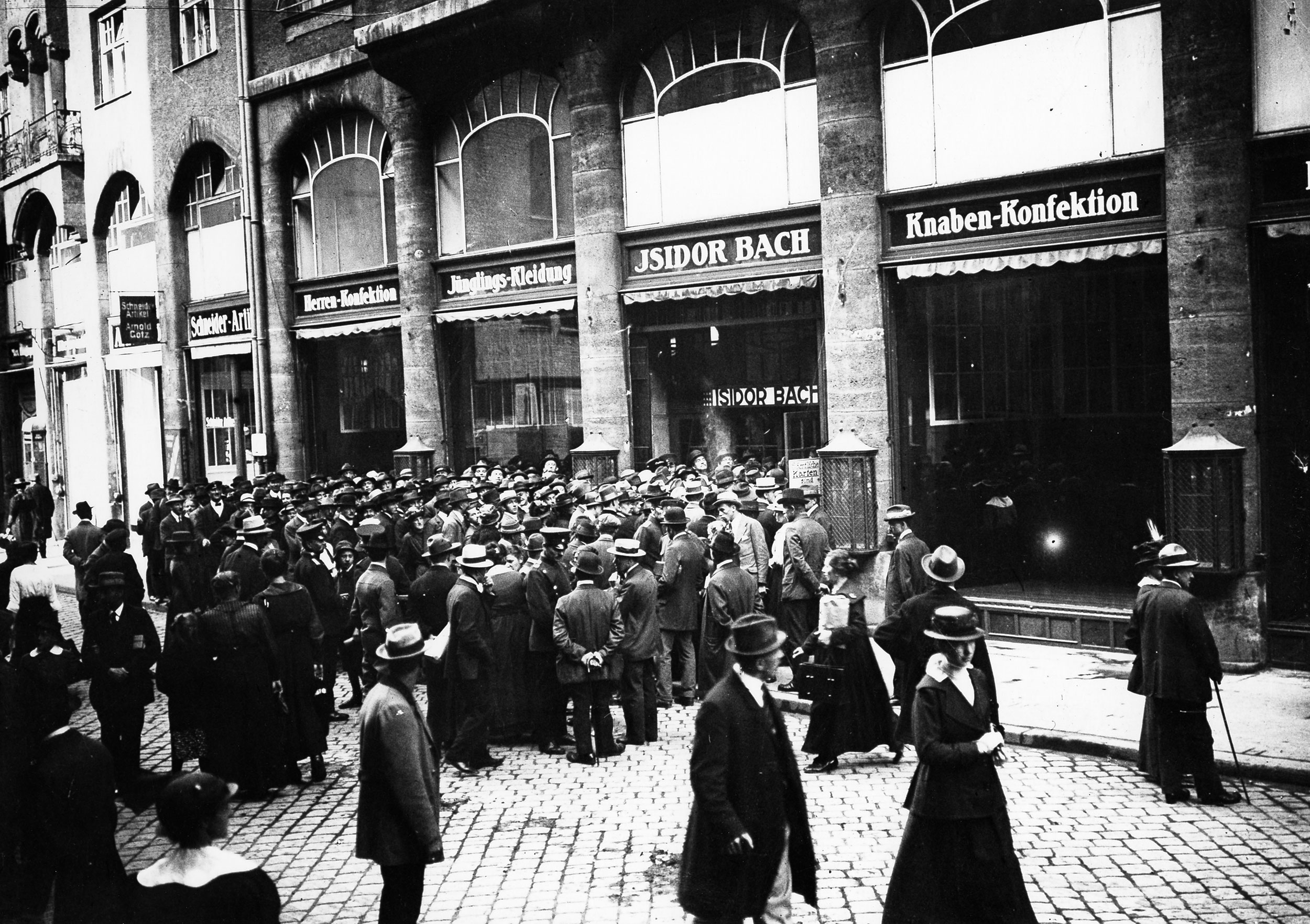

It seems that the elderly Jewish businessman Isidor Bach (1849–1946) himself had a very direct encounter with National Socialist gangsterism in its early days (and possibly with the future Führer himself). During my rummage through the history of the store, I came across an ominous photograph of it, a print of which is now in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Bavarian State Library) in Munich. It was taken in 1922, only a decade after Holhwein had designed the poster.

Isidor Bach department store

The photograph shows an anti-Jewish demonstration in front of the Bach emporium by residents protesting what they claimed was unfair Jewish commercial dominance of the area. Bach had founded the clothing store in Augsburg in 1872; he opened the Munich branch in 1878 and moved it to a new four-story building in the Sendlinger Strasse, a long-established shopping street, in 1903. An opulent brochure published in that year celebrated the 25th anniversary of what it described as “the largest specialist shop in the industry in southern Germany.”

A year after this photograph was taken, Isidor Bach was among the hostages dragged to the Bürgerbräukeller (beer hall) during the Beer Hall Putsch (or Munich Putsch) of November 8 and 9, a failed attempt by Adolf Hitler, leader of the rising National Socialist Party, and Erich Ludendorff, an aggrieved World War I general, to overthrow the Weimar government. Bach was soon released with the other hostages. But a decade later, Hitler became chancellor of Germany, and in 1936 the Isidor Bach store was “aryanized,” forcibly sold to one of its non-Jewish employees, Johann Konen, in an all-too-common subterfuge. Bach and his family went immediately into exile, emigrating to Switzerland in 1939; he died in Bern in 1946 and was buried in Munich (I am grateful to Gerhard Mittermeier of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek for clarifying the information about Bach’s life after his forced eviction). The store was partially restituted to the surviving family members after World War II when they became joint owners, but it continued to operate under the name of Konen. In 2006, the proprietors shamelessly celebrated the 70th anniversary of what they described as “the traditional Konen fashion store,” thus setting its origins at its date of aryanization. In spite of the resulting public debate in Munich about the responsibility of such businesses to acknowledge their unsavory histories, the store continued to operate under the Konen name until it was taken over by the Breuninger chain in 2021.

On a happier note: in 1992, Peter H. Bach (1914–1998), the grandson of Isidor, set up a foundation to purchase Jewish objects and this provided the inspiration and the founding collection for a new Jewish Museum in Munich, inaugurated in 2007. A small exhibition on the foundation and the Bach store was held there in 2010.