The Laboratory of Hallucinations: Posters for the Grand Guignol

.The grisly, amoral dramas featuring madness, severed limbs, hallucination, and terror staged at the Grand Guignol Theater in Paris were frequently so bloodcurdlingly realistic that a doctor was employed to revive the spectators who fainted each night in the auditorium—and he was hired only partly as a publicity stunt. As someone who starts to feel dizzy watching a nature program for the under-5’s on birds of prey in East Anglia, I would, of course, never have set foot in such a place. This unsavory location nonetheless retains a certain fascination, if only at the safe distance of many decades. Poster House has in its collection some of the lurid posters that promoted the Grand Guignol between 1897, when it opened in a spooky former chapel at 20 rue Chaptal in the red-light district of Pigalle, and 1962, when it closed its doors for good.

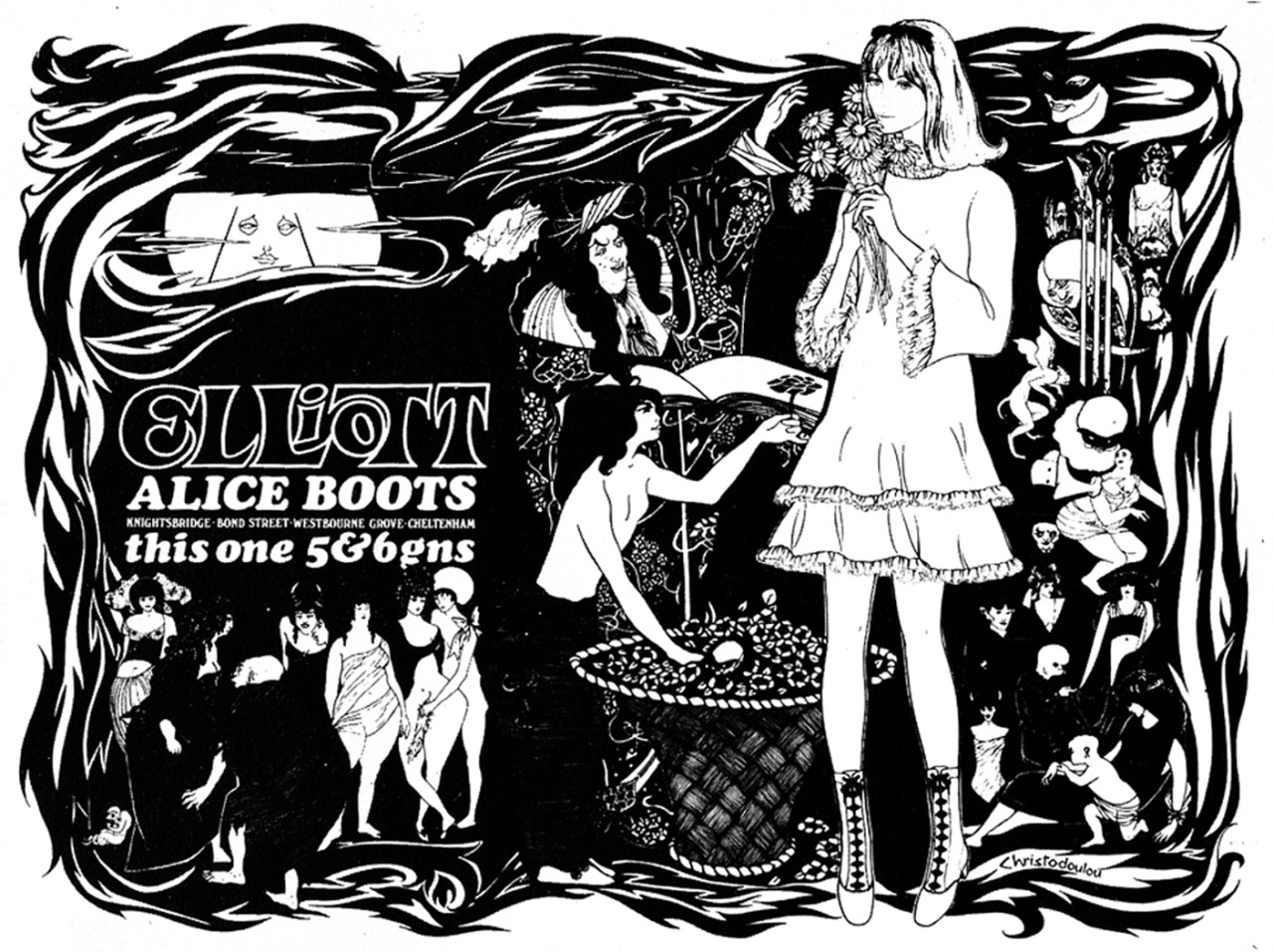

Le Grand Guignol (1897), Jules-Alexandre Grün

Poster House Permanent Collection

The Grand Guignol was one of many new performance venues that opened in Paris during the last three decades of the 19th century, among them cafés-concerts, music halls, and theaters, and it quickly developed a reputation as among the sleaziest of them. This poster by Jules-Alexandre Grün advertises it in 1897, the year it was opened by Oscar Méténier as a theater of naturalism; his initial dramas actually focused on the brutal reality of the lives of the Parisian lower classes—the vagrants, prostitutes, and con-artists—rather than on the gory horrors with which its name quickly became synonymous. Grün was a painter, caricaturist, and poster designer who had trained under the great Jules Chéret but a theater like the Grand Guignol would not have been able to afford the six hundred francs the distinguished Art Nouveau artist charged to design a poster at this point. That was for larger and somewhat more respectable enterprises like the Folies-Bergère and the Moulin Rouge, just steps away.

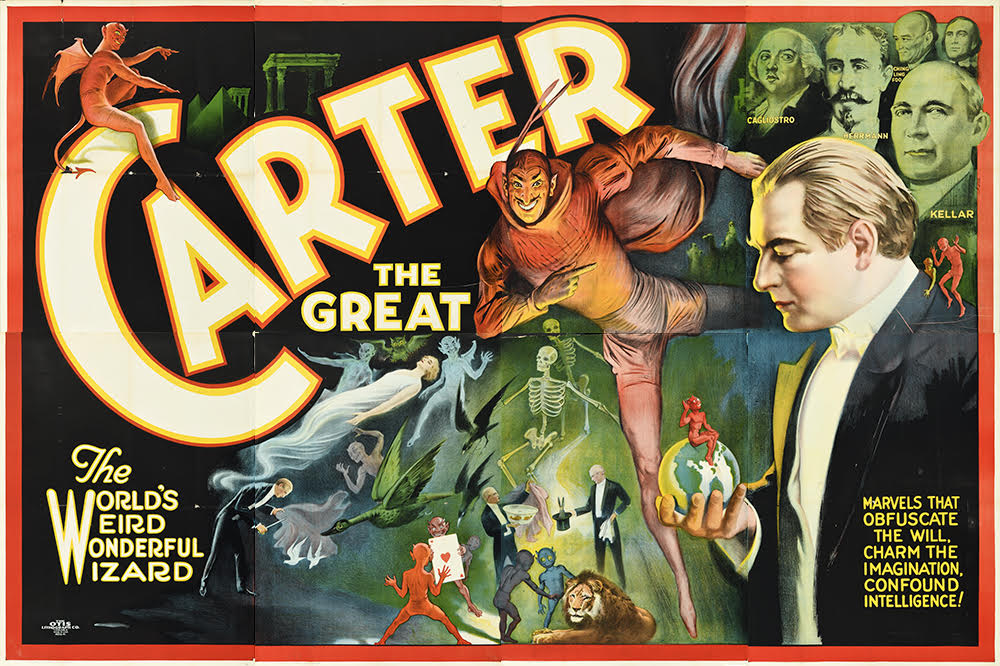

Left: Folies-Bergère/La Loïe Fuller (1897), Jules Chéret

Image: Wikipedia

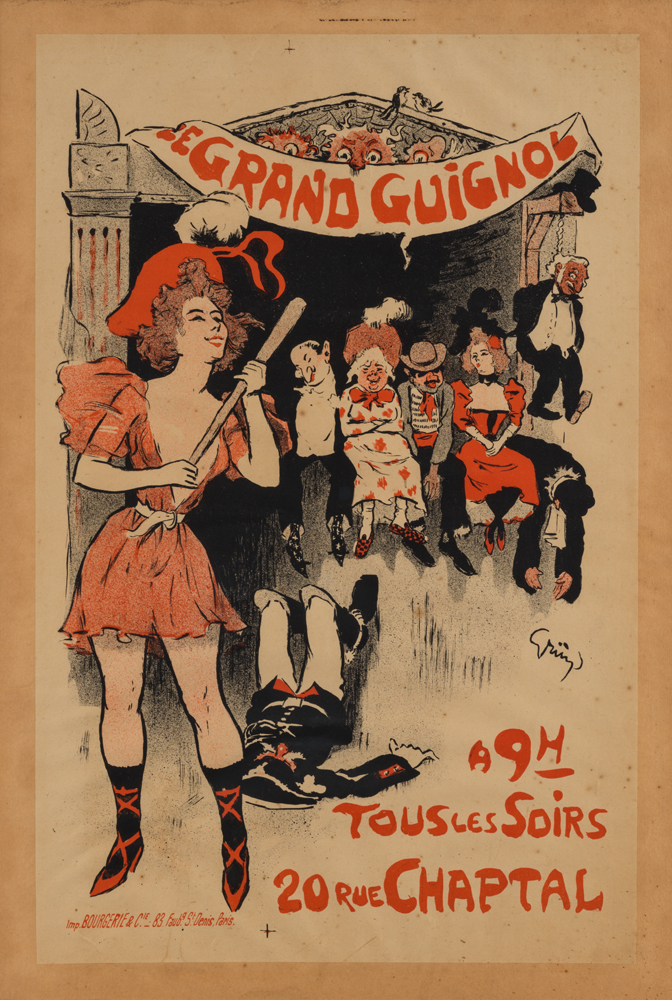

Right: Bal au Moulin Rouge (1889), Jules Chéret

Image: Swann Auction Galleries

As the image in this poster indicates, however, even the theater’s naturalistic dramas were also intended to be titillating. The cheerful prostitute in her risqué costume suggestively holding a baton, and the various grotesque characters lolling and grinning behind her, as well as an (apparently) dead soldier, point to the tenor of some of the scenes that awaited the visitors they lured to the Grand Guignol.

But in 1898, the theater’s new director, Max Maurey, shifted the program away from the seedy life of the city streets in favor of clinical insanity, deranged surgeons, murderous nannies, necrophiliacs, and serial killers. (He was also rumored to judge the success of an individual play by the number of patrons who fainted as they watched it). Maurey was the consummate showman, too, taking out ads in the Parisian newspapers showing audience members receiving medical exams before being allowed to enter the theater, and publicizing his hiring of a physician to tend to them during performances.

By 1900, the Grand Guignol was flourishing; Maurey hired Andre de Lorde, a quiet librarian by day but the self-proclaimed “Prince of Terror” by night, to write plays for it, and was the first to show lunatic asylums and operating rooms on a theater stage. Just a few of the titles of de Lorde’s 150 or so works give the flavor of the hideous medical and psychodramas in which he specialized: A Crime in the Madhouse, The Horrible Experiment, and, perhaps the theater’s most notorious production, The Laboratory of Hallucinations, about a doctor who performs a sadistic surgery on his wife’s lover (it gets much more gruesome from there).

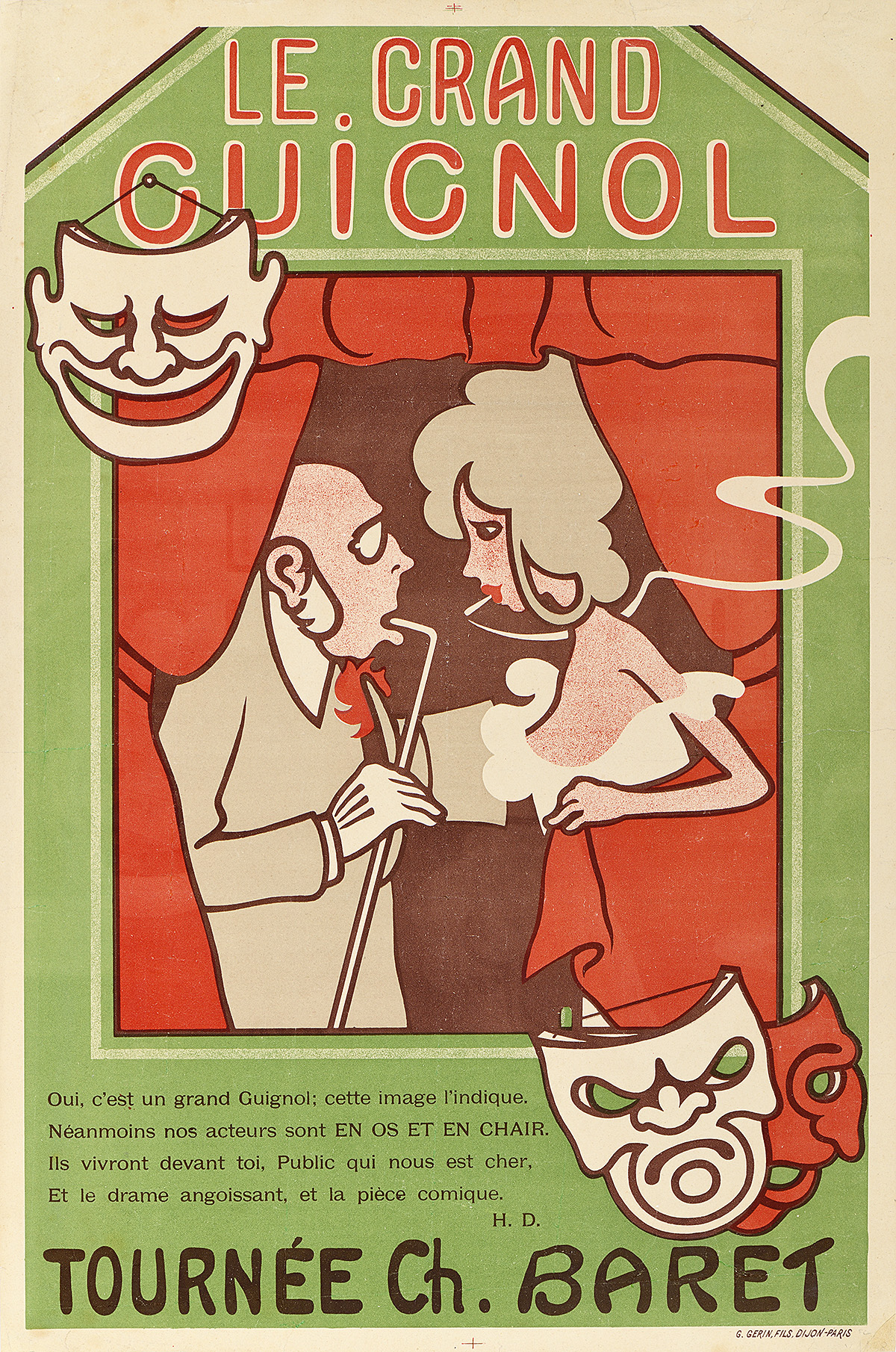

Le Grand Guignol (c. 1900), Gustave-Henri Jossot

Poster House Permanent Collection

But the Grand Guignol was not all horror. The directors built up the anticipation by alternating two grisly dramas with two sex comedies or lighter pageants during a typical evening comprising five or six small plays. As Gustave-Henri Jossot’s poster here, produced around 1900 for one of impresario Charles Baret’s theatrical spectacles at the theater, states “Oui, c’est un grand Guignol; c’est image l’indique./Neanmoins nos acteurs sont EN OS ET EN CHAIR./Ils vivront devant toi, Public qui nous est cher,/Et le drame angoissant, et la piece comique.” (Yes, it’s a great spectacle; this image demonstrates it. Nonetheless, our actors appear in the bone and in the flesh. They will live before you, our dear public, both in the scary drama and in the comic piece).

The simple composition, described in the pure, flat colors of the graphic style of Cloisonnism, shows an encounter between a lecherous old man and a scantily clad young woman smoking a cigarette. It is very similar to much of Jossot’s graphic work as a caricaturist, both for his own books and for such Paris journals as L’Assiette du Buerre. In this satirical weekly magazine featuring socialist and anarchist illustrations, he lampooned the habits of the bourgeoisie and condemned the violence and racism of the French church, state, and military.

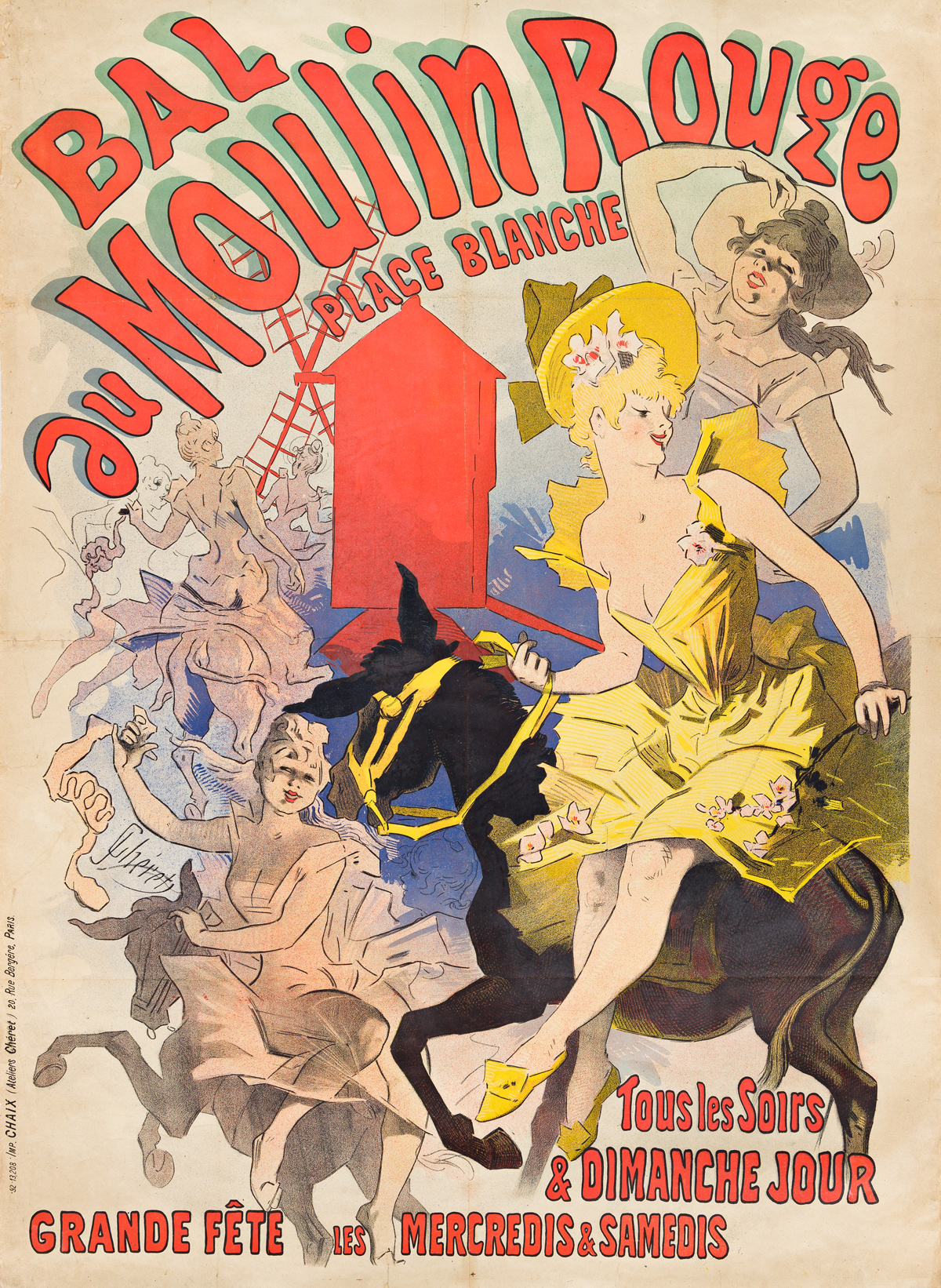

Grand Guignol/La Sorcière (1961), Designer Unknown

Poster House Permanent Collection

La Sorcière (The Witch) of 1961 was one of the last plays presented at Grand Guignol, which closed the following year. This occult-themed tale by the popular dramatist Eddy Ghilain appeared while Christiane Wiegant was director of the theater (she also seems to have acted in and produced some of the plays shown at the theater in its final years). Ghilain wrote numerous dramas for the Grand Guignol between 1957 and 1962, often serving as actor and set designer for these works as needed. (The very fact that these figures had to take on so many disparate roles at this stage is telling). The poster, by an unknown designer, shows a mostly nude woman impaled on a stake and dripping blood as the smoke from the kindling below her rises in the night sky to form a question mark; it is characteristic of the melodramatic style of the theater’s promotional imagery from the very beginning.

Le Main de Singe (1930), Paul Colin

The Grand Guignol never really recovered its popularity after World War II. Its last director, Charles Nonon, believed that “We could never compete with Buchenwald. Before the war, everyone believed that what happened on stage was purely imaginary; now we know that these things and worse are possible.” But there were other reasons too. The theater’s reputation was tainted by its popularity with the German occupiers during the war and it became dependent mainly on tourists as Parisians of all kinds as well as celebrities and foreign royalty abandoned it. Even during the 1930s, the theater had begun to experience a downtown when its new director, Jack Jouvin, substituted much of the gore and the flying limbs and eyeballs with intense psychological dramas. He also made the mistake of firing Paula Maxa, the theater’s great star since 1914, known as “The Most Assassinated Woman in the World.” In addition, by the time this poster was issued, the dramas had largely devolved into self-parody and kitsch. A New York Times journalist noted on March 17, 1957, “As a result, the Grand Guignol is no longer, for the up-to-date Parisian, the fashionable attraction that it once was. He spurns it just as he would blush with shame if his friends saw him at the Folies Bergère or on the platform of the Eiffel Tower.”