Female Spies of World War II

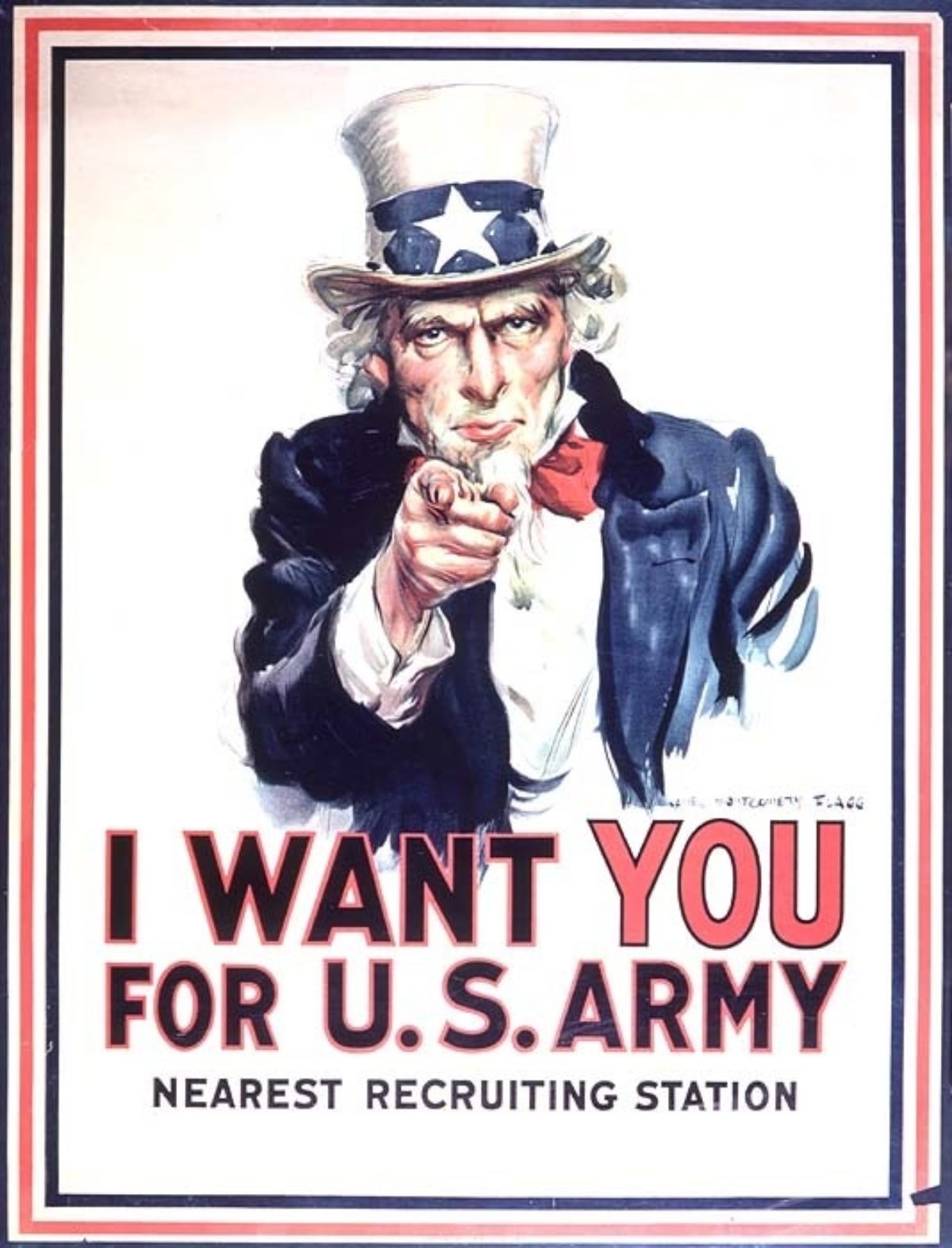

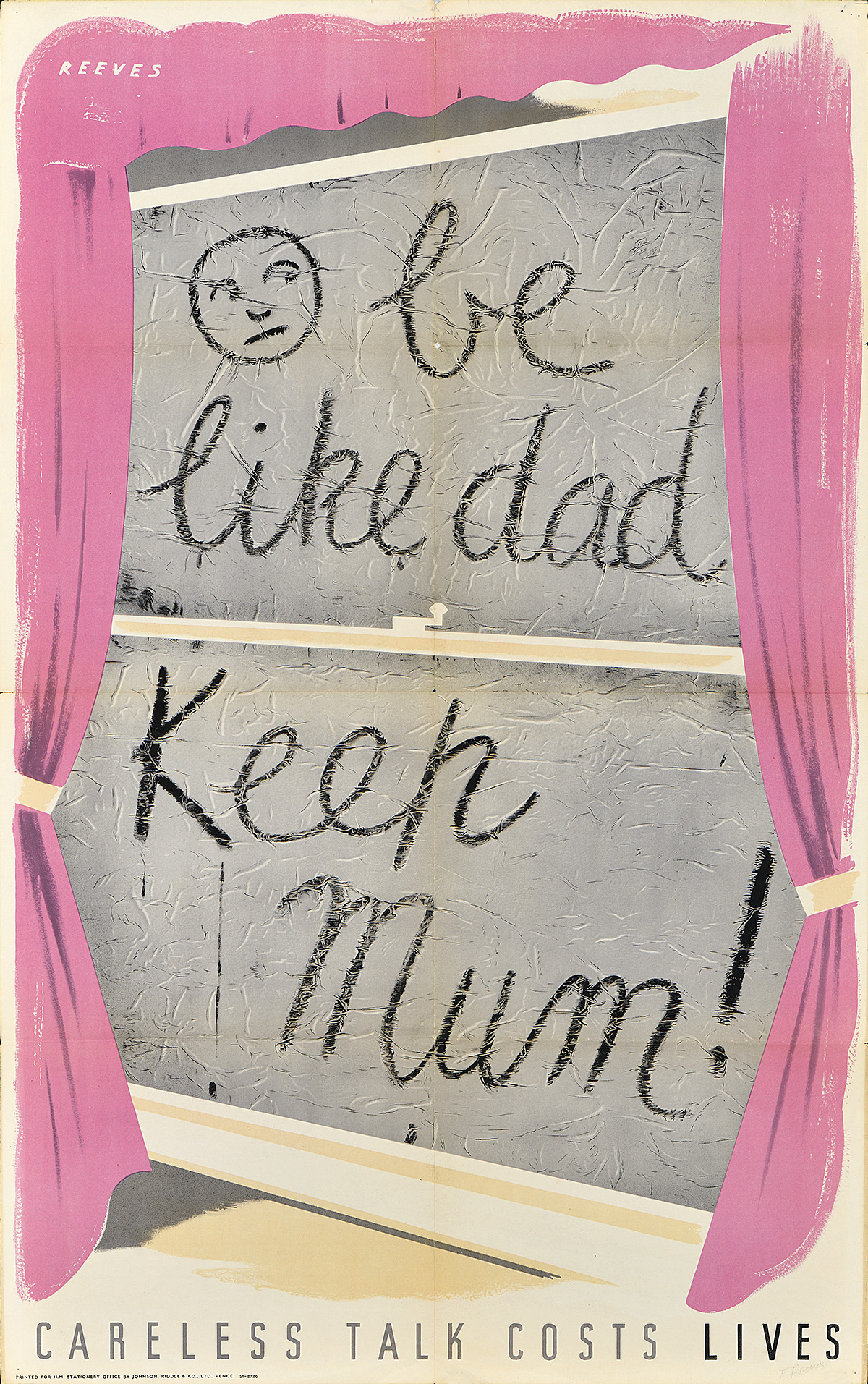

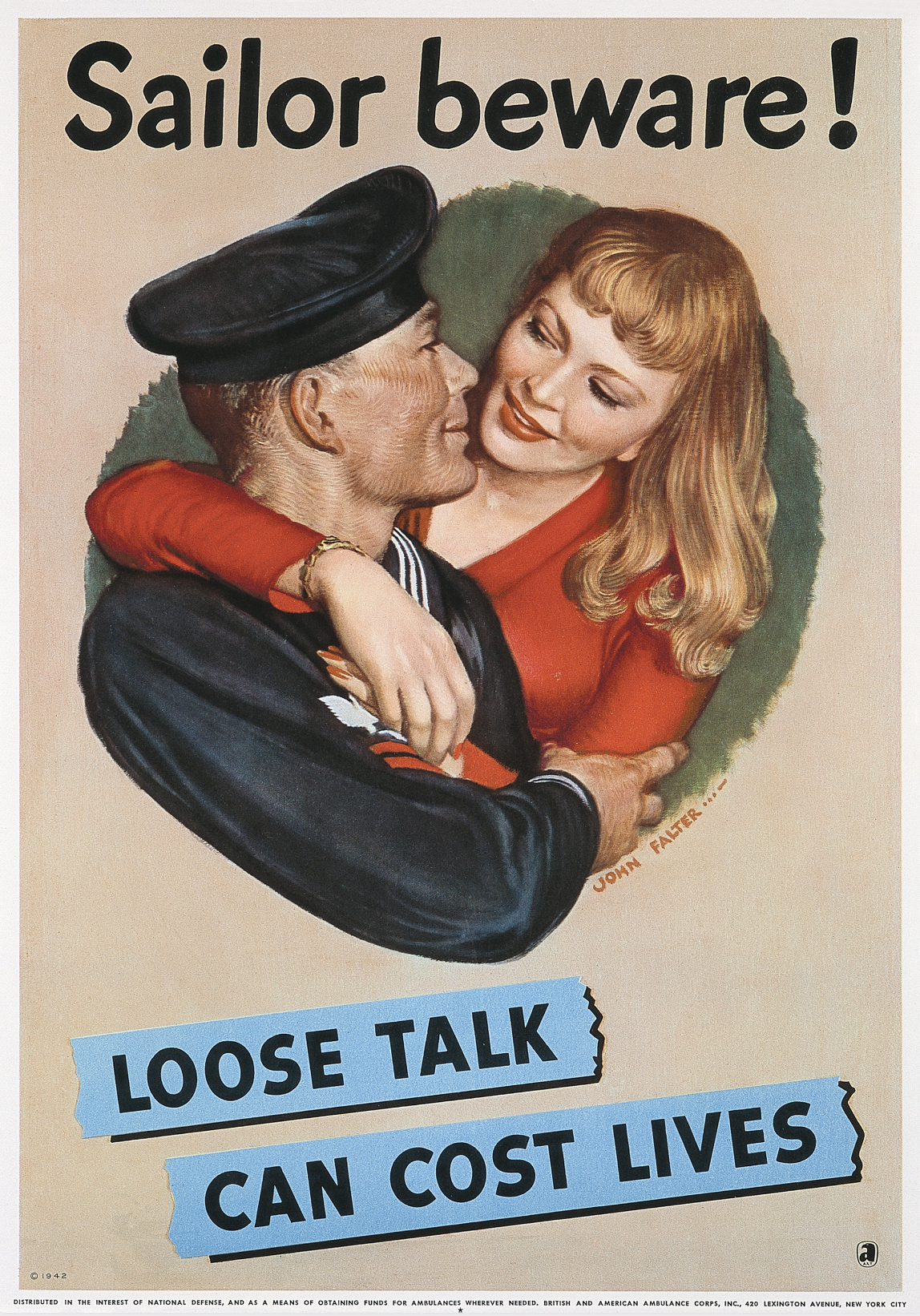

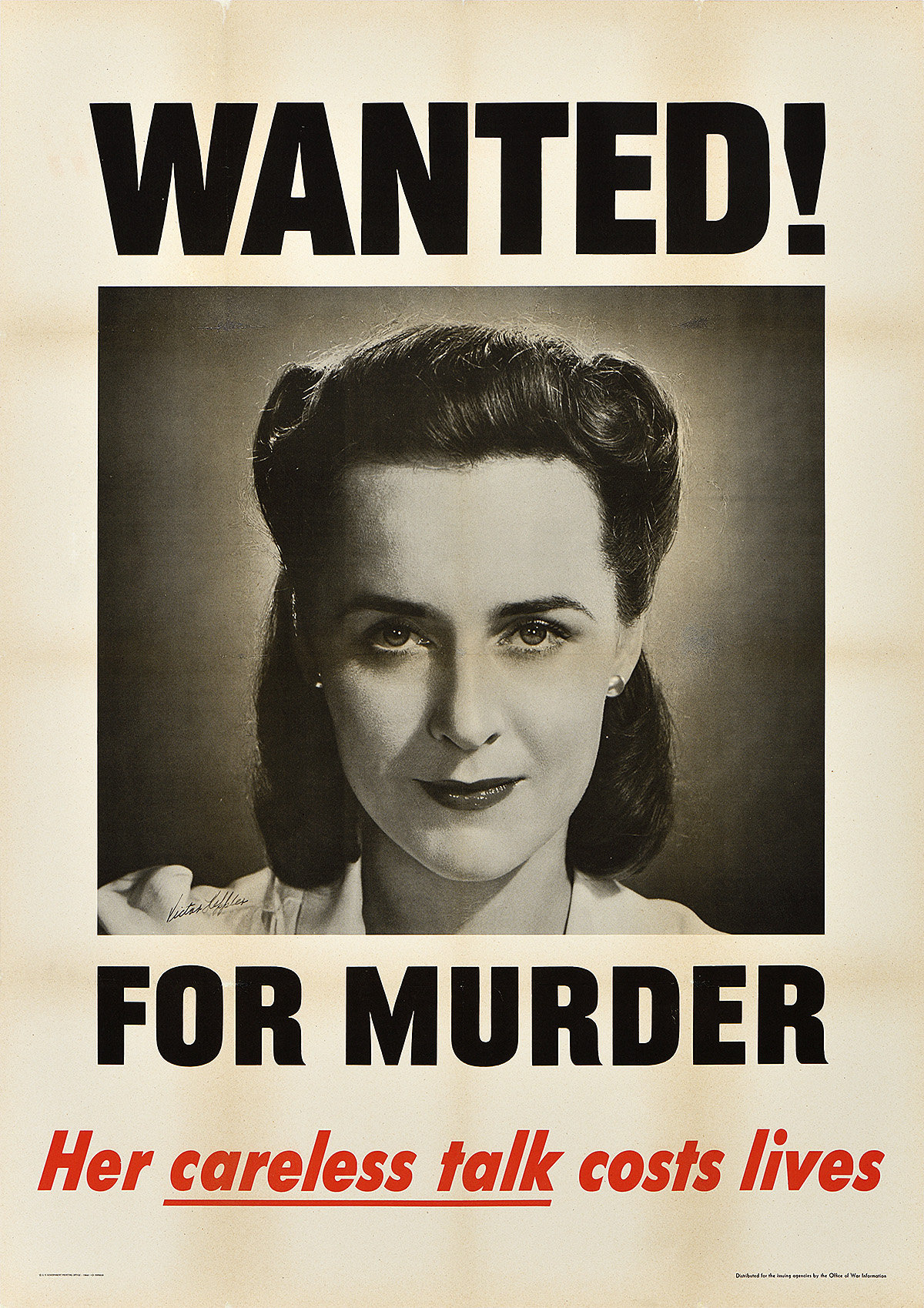

.In May 1941, a Labour MP in the U.K. stood up in Parliament and asked the Minister of Information whether he understood that a particular anti-espionage poster campaign titled “Be Like Dad, Keep Mum!” being broadly distributed at the time was offensive to women. Some eighty years later, while looking through posters for a potential show I was curating of World War II anti-espionage propaganda from the U.S.A., U.K., Canada, and France, I felt similar indignation. Most images featuring women suggested, at best, that they could not be trusted to be quiet or that they were femme fatale types that would seduce men for information (these designs conveyed this sentiment through graphics similar to those warning soldiers of venereal disease). Lastly—and most memorably—one poster brazenly suggested that women were just wanted for murder for intentionally spreading gossip.

With many men fighting abroad, women were anything but dangerously malleable figures. Most were ensuring that the homefront functioned, while many others were stationed in war zones themselves. A select few, however, took on the most dangerous work behind enemy lines.

Left: Sailor Beware!, John Phillip Falter, 1942

Right: Wanted! For Murder, Victor Keppler, 1944

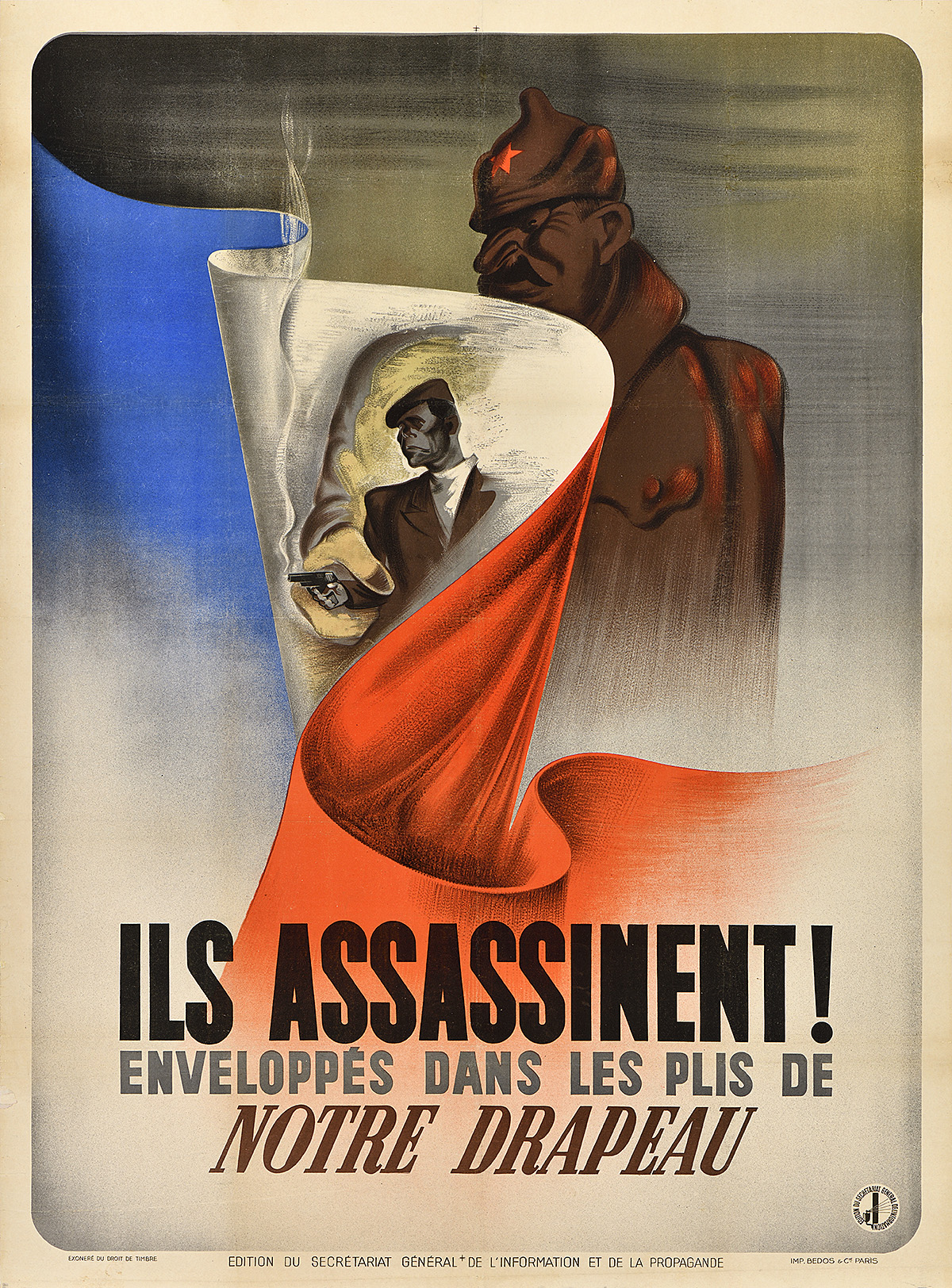

Of the posters in this show, the most historically interesting were produced in France, reflecting the three distinct phases the country experienced during the war: 1939–1940 when it was fighting the Nazis, 1940–1944 when it was occupied and under a collaborationist government, and 1944–1945 when it was liberated. The poster featured from this middle period—Ils Assassinent! by Raoul Eric Castel—shows a resistance fighter firing a gun, his hand manipulated by a shadowy figure of Stalin. While communist resistance fighters existed at this time, the more organized and effective were those assisted by the British, making this poster alarmist at best and inaccurate of the actual “enemy.”

Ils Assassinent!, Raoul Eric Castel, 1941

It is notable that none of the French posters in this show feature women as protagonists—an ironic fact given that many of the best spies in the world during World War II were female. Numerous women worked for the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a British-based organization dubbed the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare,” and were responsible for espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance while Winston Churchill mandated them to “Set Europe Ablaze.” President Eisenhower estimated that the incredible actions of the SOE shortened the duration of the war by a remarkable six months.

From April 1942, women could officially be deployed in the field on the very simple notion that they were less likely to be noticed. Nazi propaganda at the time had women’s lives revolving around Kinder, Kirche, Küche (children, church, kitchen), and the collaborationist Vichy French government professed a clear ideology of women having a natural destiny as modest frugal procreators. As such, the concept of women as spies was anathema to both regimes, a conscious bias that ultimately became advantageous for the extraordinary women who served in the SOE in France.

While there are truthfully too many to list, two Allied female spies in particular stand out:

Photograph of Noor Inayat Khan c. 1943

Image: Wikipedia

Noor Inayat Khan, a pacifist daughter of a Sufi preacher, went into France as a radio operator. At this time, this job had the shortest life expectancy of any SOE operative. On average, a radio operator would last six weeks in the field before their signals could be triangulated, their bulky equipment making it nearly impossible to get away quickly. Before her capture, Khan was doing the collective work of the six radio operators in the Paris region that had already been caught. Even though she was offered the opportunity to cease and escape, she stayed.

If captured, agents were expected to maintain silence for 48 hours, but could talk after that period passed. Under intense torture over ten months, Khan revealed nothing, not even her name. She attempted escape multiple times, but ultimately was transferred to Dachau and shot. In 1949, she posthumously received the George Cross, Britain’s highest civilian honor. Three years earlier, in 1946, the French had already presented her with the Croix de Guerre, their highest military award.

Photograph of Virginia Hall

Image: NPR

Virginia Hall was another incredible female spy operating for the SOE behind enemy lines. Born in America, she was deployed in 1941 under the cover of being a journalist. Once the U.S. entered the war, this identity was no longer viable, and she went from gathering intelligence to organizing and leading multiple resistance cells. She was easily recognizable, having a pronounced limp from a prosthetic wooden leg (which she’d named “Cuthbert”). At one point, she radioed base to let them know that Cuthbert was giving her trouble. Misunderstanding the situation, the pithy reply came back telling her to “eliminate him!”

Known throughout enemy territory, the kindest epithet she was given by the Gestapo was “the limping lady.” Klaus Barbie, the infamous “Butcher of Lyon,” described her less politely, viewing her as the most dangerous Allied spy, and so published a poster revealing her identity to the public. Despite this, she was never captured—though at one stage had to escape by climbing over the Pyrenees into Spain (an extraordinary feat given Cuthbert). She returned to France to lead ever more audacious disruptive teams against the occupying forces. She received the Member of the British Empire from Britain, the Croix de Guerre from France, and the Distinguished Service Cross from the U.S.

Photograph of Josephine Baker

Image: History.com

It would be impossible to discuss notable female spies operating in France during World War II without mentioning Josephine Baker. The subject of many famous posters, she is most known as a legendary performer in her adopted country of France. As a spy, she placed herself in great danger, sheltering Jewish people in hiding as well as French resistance fighters. She used her celebrity to attend society events to gain information, acted as a courier for vital intelligence, and toured in fascist Spain and occupied North Africa with many of her troupe also acting as undercover spies.

She ultimately donated much of her fortune to the resistance, believing strongly in the necessary freedom of the French people. From 1951 to 1963, the F.B.I. banned her from traveling to the United States as they believed she was a communist due to her refusal to perform for segregated audiences. She was awarded both the civilian Legion d’Honneur and the military Croix de Guerre, and is one of eighty French heroes with a tomb in the Pantheon, the highest honor in the country since Napoleonic times. She is only the sixth woman afforded such accolades in French history, and the only Black woman.

Although it is in the nature of spies to operate in the shadows, it is only in recent years that the heroism of these women has come back into focus, with a number of books written about them. After the Second World War, Virginia Hall joined the CIA, but faced widespread discrimination from men who felt threatened by her superior record. It was only in 2016 that a building at Langley was named after her, the CIA acknowledging that her work in France continues to provide a template for collecting intelligence and recruiting, arming, and equipping local groups to engage in covert operations.

Looking to shop the show? You can browse all the exhibition-related apparel, books, and home goods in person at our Shop or online here.