The Prolific Peter Strausfeld

.We live in an era of franchise movies, manufactured by an industrial process that melds globally famous film stars with narratives created by teams of writers, whole rafts of Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI) technicians, cohorts of stuntmen, and other technical staff scattered around the world. The purpose of these films is to ensure financial success in a repeatable, scalable fashion that allows for commercial spinoffs and product placement.

The antithesis of this is the “art house film,” generally based around a director’s personal vision, telling a very specific story, typically made on a shoestring budget, and often featuring unknown actors who may actually be family members of the director. The golden era of such films was the 1950s through the 1970s when auteur-directors from around the world found ways of crafting distinctive visual narratives that reflected the particular culture of their home countries as they stumbled out of World War II and faced new regional and local conflicts.

My Night with Maud (c. 1969) by Peter Strausfeld

Collection of Michael Lellouche

These films were not shown by the cinema chains in ever-expanding movie-theater complexes, however, but by independent, stand-alone cinemas that sought to build relationships with the directors and producers of such works. In the UK, one such entity, the Academy Cinema, operated in London more or less continuously between 1931 and 1986. As a boutique operation showing films for a select audience, the management of the cinema also decided to eschew the standard posters produced and distributed by the film companies themselves and hire one man, Peter Strausfeld, to design all its posters between 1947 and his death in 1980. During that period, Strausfeld created more than three hundred posters, all deceptively simple, predominantly single-color linocut compositions with a hand-printed feel. They were first posted at bomb sites all over London, ultimately becoming fixtures on the London Underground system known as the Tube.

The Shame (1968), by Peter Strausfeld

Collection of Michael Lellouche

Strausfeld’s background is a fascinating tale in itself. Born in Germany, he arrived in the UK in 1938 as a political refugee from the Nazi regime. Early in World War II, like most German citizens, he was interned as an enemy alien. There he met and befriended George Hoellering, an Austrian-born film producer who was also the deputy general manager of the Academy Cinema. After his release in 1941, Strausfeld was hired to make animated propaganda films for the British government and was later hired by Hoellering. He also taught graphic design and worked as a book designer, cartoonist, and art director.

This blog is intended as a little sneak preview of Poster House’s exhibition of Strausfeld’s posters for the Academy Cinema, Art for Art House: The Posters of Peter Strausfeld, opening on November 13. I have picked films from different countries and by different directors to provide an overview of the work of this underappreciated artist. It is worth noting that in these posters the director’s name usually gets top billing, in contrast to typical studio-issued works in which the names of film stars who carry the vehicle get the primary slot. How many of you can name the directors of the Mission: Impossible movies, in spite of the fact that they are among the most commercially successful?

Juliet of the Spirits (1966), by Peter Strausfeld

Collection of Michael Lellouche

The first two posters are for films by directors who became so famous that their names are now adjectives in the description of movie style: the Swede Ingmar Bergman (Bergmanesque) and the Italian Federico Fellini (Felliniesque). Bergman’s somewhat bleak films explore the absence of God and dysfunctional human relationships while Fellini favored riotous color and decadent fantasy, but the works of both directors served as meaningful counterpoints to the often saccharine, optimistic films emerging from Hollywood after the war.

Shame, 1968. In his poster for Bergman’s Shame, Strausfeld weathers Liv Ullmann’s complexion; her face effectively carries the stresses of the film, which shows the terrible disintegration of a couple’s relationship as they try (and fail) to avoid the horrors of war.

Juliet of the Spirits, 1968. In this poster for Fellini’s first color film, Strausfeld captures its bizarre, dreamlike, surreal nature in the pink and blue tones of the fantasy world behind Juliet, who appears in black and white in the foreground. Fellini’s actual wife, Guilietta Masina, played the lead role.

Ashes and Diamonds (c. 1959) by Peter Strausfeld

Collection of Michael Lellouche

My Night with Maud, 1969. When we think of art house films, many of us imagine a certain kind of French film, riddled with ennui (a French word, for God’s sake) and based on an ambiguous plot featuring angst-ridden characters seeking personal meaning in an absurd universe. For an example of a French film poster here, I have therefore chosen Strausfeld’s design for Eric Rohmer’s My Night with Maud, a film that certainly ticks all the boxes; it’s a love quadrangle in which the philosophical and ethical positions of the characters on religion, mathematics, and love are gradually revealed. As Rohmer himself observed, “what matters is what they think about their behavior rather than their behavior itself.” The tortured expressions of the characters in the poster perfectly capture the underlying ethos of the film.

Ashes and Diamonds, 1959. As the Polish director of this film, Andrzej Wajda, stated: “When asked what is behind the Berlin Wall? The Polish directors of the 1950s gave the truest answers of anyone in the Eastern Bloc.” The film depicts the chaos of post-World War II Poland, detailing a former resistance fighter’s attempt to assassinate the local secretary of the Polish Workers’ Party. Central and Eastern European directors produced marvelous films after the death of Stalin in 1953 as some censorship rules were loosened. Nonetheless, they still often resorted to satire or surrealism to evade the censors. Some, like the Czechoslovakian director Milos Forman, were forced into exile by unforgiving regimes.

The Chess Players (1977), by Peter Strausfeld

Collection of Michael Lellouche

The Chess Players, 1977. Although India has its own commercial film studios, among them the famed Bollywood, it also has its own art house films. These became known as parallel cinema, and originated in West Bengal in the 1950s, inspired by Italian neorealist film. By far the most famous director in this firmament was Satyajit Ray. This poster is for Ray’s only full-length Hindi-language film; the rest are in Bengali. Strausfeld’s image captures the languid lifestyle of the two main characters as their states fall to the rapacious British Empire.

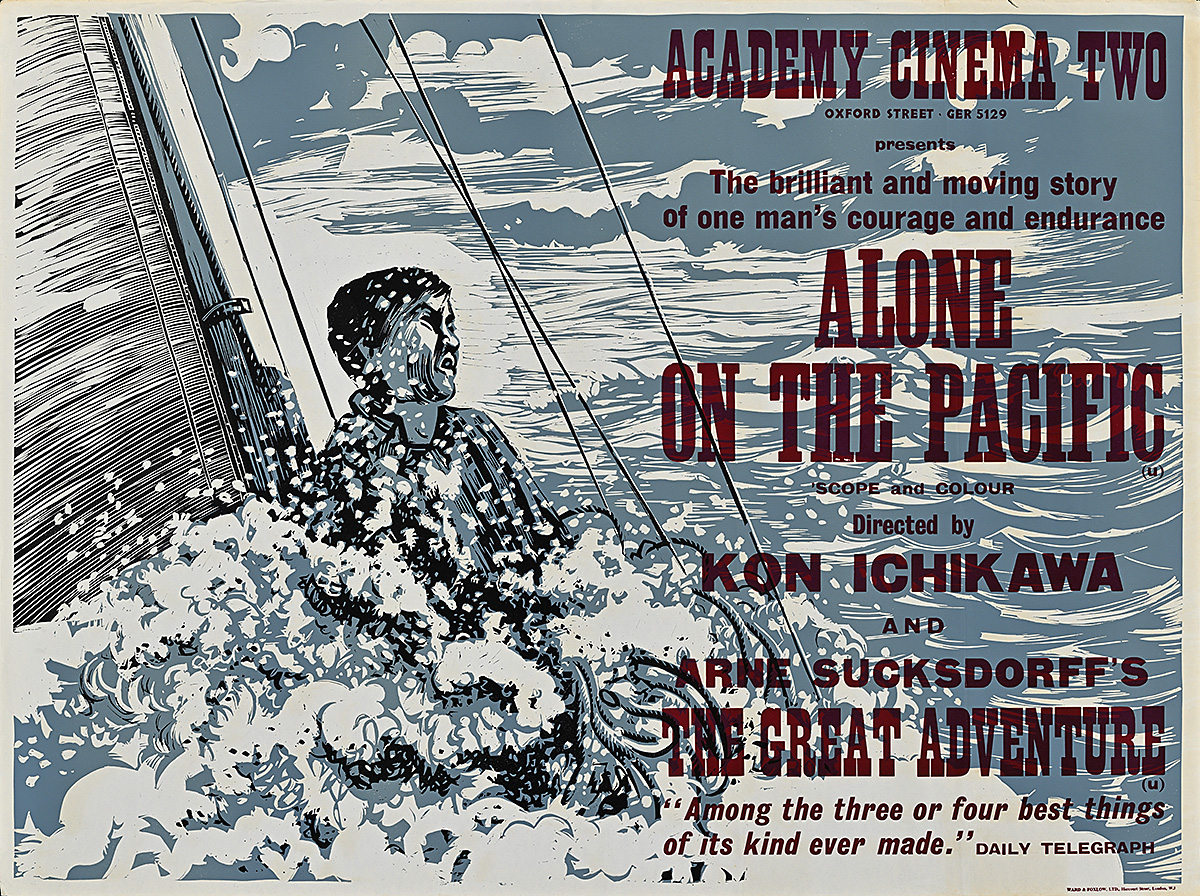

Alone on the Pacific, 1967. Strausfeld taught graphic design at Brighton College and was obviously familiar with Hokusai’s famous 1831 print The Great Wave off Kanagawa, whose forms are reflected in the swirling, foaming sea around the solitary sailor. Kon Ichikawa’s film is a dramatization of Japanese solo yachtsman Kenichi Horie’s actual, 92-day odyssey across the Pacific Ocean in 1962. The film ends with his arrival in San Francisco and is the first Japanese feature shot on location in the United States. (The film was made a year after the event but not released in the UK until 1967.)

I hope this little snapshot whets your appetite for the exhibition itself and for the small book that will be published at the same time.